3 Expanding the prison library

At first many libraries consisted of collections of religious books already in the prisons.

As early as 1823, concerns were expressed that the exclusive diet of Bible reading and religious tracts at Millbank Penitentiary had led to feelings of depression and low spirits among the convicts serving long periods of separate confinement there (Select Committee on the Penitentiary at Millbank, 1823, p. 4). Despite the enthusiasm of the prisoner quoted in Activity 1 (Part 2), similar concerns were raised about the programme of Bible reading at Reading Gaol in the late 1840s when prison health statistics showed a worrying increase in the number of prisoners being sent to the asylum (Crone, 2012).

Moral, secular tracts were added to prison libraries, as were educational works which could expand upon the subjects taught in the schoolroom, such as history, geography and mathematics. Additions at some prisons also included books on natural history (studies of wildlife and plants), practical works to assist with learning a new trade or skills for a new occupation (such as domestic service), and self-help books, including those on managing personal or family finances.

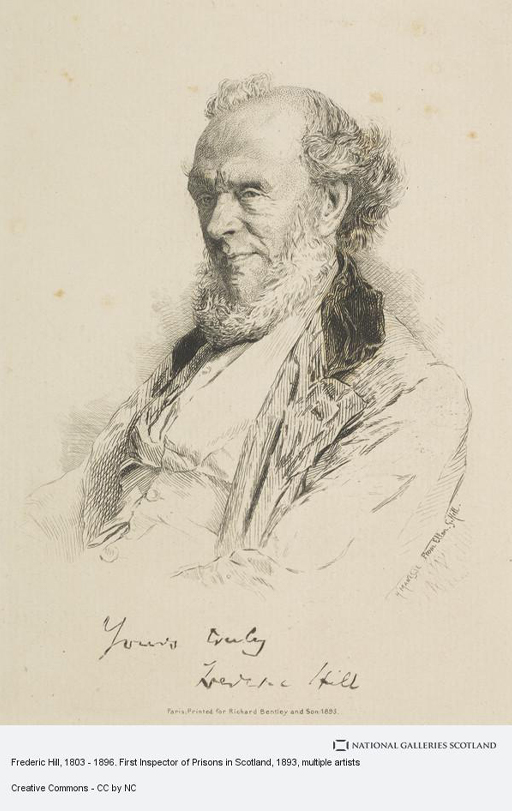

From the late 1830s, some prison chaplains, and the inspector for prisons in Scotland, Frederic Hill, began to argue that prison libraries should also include some lighter literature. Hill believed that amusing but moral stories would encourage those who could not read to make efforts to learn (Inspectors, Scotland, 7th Report, 1842, p. 8). The chaplain at Glasgow Prison argued that prisoners on long sentences in particular needed to be kept cheerful, by reading entertaining books as well as books of a serious character (Fyfe, 1992, p. 48).

The expansion of the prison library led to a vigorous debate about what was appropriate reading material for prisoners – what could encourage them to reform, what risked easing the pain of their imprisonment, and what had the potential to make them more criminal.

Activity 2 The dangers of reading

In the late 1840s, the journalist and social investigator, Henry Mayhew, organised a meeting in the schoolroom of the British Union School in Shadwell, London. He put up a notice inviting thieves and vagabonds (the homeless) who were under 20 years old. One hundred and fifty attended the meeting. Mayhew used the opportunity to talk with them about their lives and habits.

Read the extract from Mayhew’s account of the meeting, and consider the following questions:

- What does Mayhew suggest led these boys into a life of crime?

- Do the boys agree with him?

Respecting their education, according to the popular meaning of the term, 63 of the 150 were able to read and write, and they were principally thieves. Fifty of this number said they had read Jack Sheppard and the lives of Dick Turpin, Claude du Val, and all the other popular thieves’ novels, as well as the Newgate Calendar and Lives of the Robbers and Pirates. Those who could not read themselves, said they’d had Jack Sheppard read to them at the lodging houses. Numbers avowed that they had been induced to resort to an abandoned course of life from reading the lives of notorious thieves, and novels about highway robbers. When asked that they thought of Jack Sheppard, several bawled out “He’s a regular brick” – a sentiment which was almost universally concurred in by the deafening shouts and plaudits which followed. When asked whether they would like to be Jack Sheppards, they answered “Yes, if the times was the same now as they were then.”

Discussion

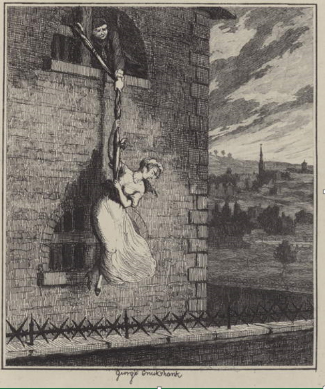

- In this passage, Henry Mayhew suggests that the reading of tales about thieves had led the boys into a life of crime. Having the ability to read and write was no protection against criminal behaviour. If anything, possession of these skills made the boys vulnerable to the effects of romantic tales about famous thieves such as Jack Sheppard – a burglar who escaped from prison four times before he was hanged at Tyburn in 1724 – and Dick Turpin – a highwayman (or street robber), active in the 1730s, who was hanged outside York Castle Gaol in 1739. The suggestion is that the boys hoped to emulate these famous thieves and lead equally exciting lives. Interestingly, the corrupting influence of such literature was not restricted to those who could read, as others were able to indulge in these stories by being read to.

- Mayhew writes that many boys said they had been encouraged to commit crime through reading about notorious thieves. Perhaps Mayhew had already suggested this idea and the boys readily agreed because it offered an easy way out. Explaining criminal behaviour and the causes of crime is complex and often painful, especially for individuals. When Mayhew asked if they would like to be Jack Sheppard, they said they would if the times were the same now as they were then. This suggests the boys did not take the tales as seriously as Mayhew believed they did.