5 Borrowing books

As suggested by the report on Lancaster County Gaol, the existence of a library in a prison did not mean that all prisoners were able to borrow books, or the books they wanted, from it. At many local prisons, access to the library was limited to prisoners who could read.

At Northampton County Gaol in the late 1840s, prisoners serving long sentences were given a wider choice than those serving shorter sentences who could only access religious books (Inspectors, Midland & Eastern, 13th Report, 1847–48, p. 82). Good behaviour also seems to have determined access in many local prisons.

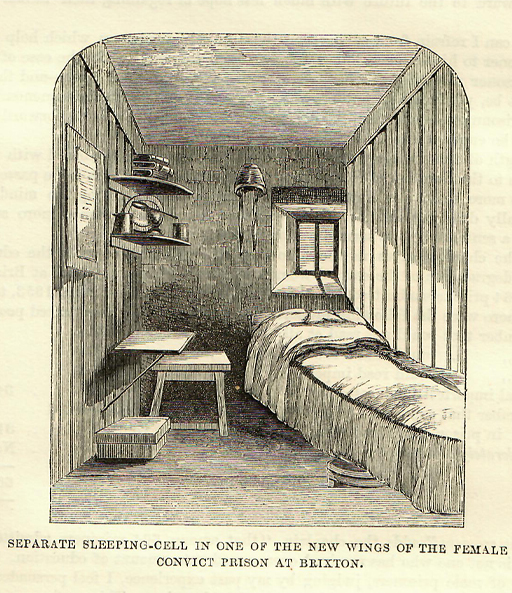

In the 1840s, convicts at Millbank and Pentonville (opened 1842) were each given a library book in addition to devotional books (Bible, Prayer Book and Hymn Book) and a certain number of schoolbooks, all to use in their cells.

At Parkhurst Juvenile Prison, the boys were not permitted to have books in their cells or dormitories. Only boys who behaved well were given the privilege of reading a library book in the evening (Reports relating to Parkhurst Prison, 1849, p. 14). At Mountjoy Prison, Dublin’s Pentonville, which opened in 1850, more stringent restrictions were applied. To receive a library book, a prisoner had to:

- pay attention to instruction imparted by the teacher at school

- if competent, write out the substance of lessons and lectures delivered in school

- practice the moral qualities inculcated by the teachers.

In 1856, the Rev. Kingsmill (Pentonville’s second chaplain) proposed the removal of library books from all prisoners except for a small class of the best educated. ‘Most only cull the stories out of the library books,’ he wrote, ‘and many grievously abuse them’ (Directors of Convict Prisons Report, 1857, p. 20). His plan was blocked by one of the prison’s directors, but there was damage to books. Prisoners tore pages out of books when they needed paper and scribbled between the text in the hope of passing on a message.

After the introduction of book-inspection systems, chaplains noticed that prisoners took better care of the books. Incidents of wilful damage were reduced largely to those in which prisoners, when venting their anger or frustration, threw whatever objects they could find in their cells.

The authorities were well aware of the value of books and reading to many prisoners. Accounts of positive and in some cases transformational reading experiences can be found in different types of sources describing life in prison. The governor at Hamilton Prison in Scotland recorded the following incident in his journal on 27 October 1845:

I was much gratified to day by learning the following interesting circumstances. The first act of a person who was liberated this morning was to go spontaneously to a stationer’s shop and purchase several of Chambers’ Miscellany of Tracts. I believe that during the time he was imprisoned here, he acquired a taste for reading, and a thirst for knowledge, which he would never otherwise have had. He was exceedingly anxious to obtain Tract No. 2 (a Tale of Norfolk Island), stating that he meant to read it to the villagers of his acquaintance who had never heard of such things.

Of course, we must be cautious when using statements about prisoners’ reading which appear in records kept by officials. Still, there must have been some truth in their claims of the pleasure that many prisoners derived from reading because, when the authorities wanted to increase the pain of imprisonment, the prison library and access to books were obvious targets.

Books in prisons could be used by prisoners who could read to practise their skills and learn on their own. They could also be offered as reward for good behaviour. While the Bible, or at least most parts of it, was considered essential reading by prison officials, they recognised that too much religious reading could be unhealthy. They also provided books to aid self-improvement, to expand secular knowledge, and even to entertain with tales of upright, loyal behaviour.

Those who did read the books did not necessarily receive the messages that the author, or the authorities, hoped they would. Books mean different things to different people. The Bible could provide a powerful message of salvation through repentance. It could also be read as a collection of captivating stories. Once a book was in the hands of a prisoner, it was the reader who had control over the meanings derived from it.

Activity 4 Reflecting on your learning

In Session 2 you were introduced to one form of reflection. Here is another way to structure your reflection. You are welcome to use either, or both suggestions. Below are the main topics you covered in Session 4. One way to structure your reflection on this part of the course is to complete the grid below, scoring on a scale of 1 (negative) to 5 (positive).

| How interesting was this section? | How much did I understand about this section? | How useful was this section? | |

| Section | |||

| 1 Books behind bars | |||

| 2 Reading in seclusion | |||

| 3 Expanding the prison library | |||

| 4 Censorship | |||

| 5 Borrowing books | |||

| Activities | |||

| 1 Notes on the video | |||

| 2 Bible reading | |||

| 3 The dangers of reading | |||

| 4 Accessing books in the library |

Revisit any topics that you scored 3 or less for ‘how much you understood the topic’. For any sections which you scored 1 or 2 for interesting, make a note about how the course might be improved.

For any sections which were not useful, try to imagine why that exercise or information was included and if you can relate the section to the learning outcomes. Once you have done this for Session 4 you can adopt the procedure for other sessions.