2 Evidence-based policymaking

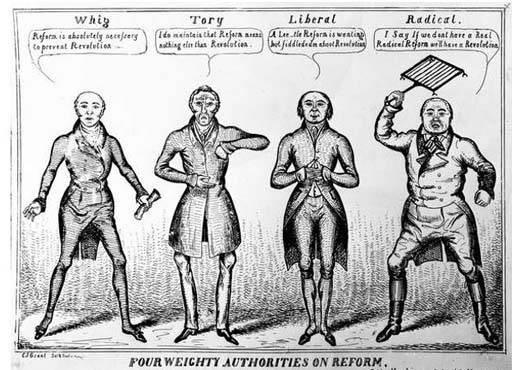

The general election of 1830 brought a new ‘Whig’ (predominantly liberal political party) government to power in the United Kingdom. Widespread political and social reform was at the top of their agenda.

They began with tackling political corruption by redrawing electoral boundaries and extending the franchise (right to vote) to the large sections of the growing ‘middle class’. Next, the government turned its attention to the social crisis being caused by industrialisation and rapid urbanisation. Poverty had expanded, the living conditions of the working classes had deteriorated, recorded crime continued to rise, and expressions of discontent were mounting.

However, in a marked departure from any UK government that had preceded them, the ruling Whig politicians wanted evidence – both comprehensive and reliable – on which to base their social policy. The search for quantitative evidence – namely statistics – was given priority. Some government departments were asked to revise and expand the statistical series they already compiled. In 1832, a new government Statistical Department was established within the Board of Trade. From 1833, new statistical societies were founded in London, Manchester and other provincial towns to support the civil service and supply the necessary numbers.

The expansion of education was once again looked to as a solution for social ills. A national system of elementary schooling had been established in Ireland in 1831 and there was appetite for something similar in England and Wales. The government resisted, claiming that there was a lack of evidence to suggest that such an expensive intervention was necessary. Instead, in August 1833, Parliament approved a Treasury grant of £20,000 to aid the building of schoolhouses by the National School Society (Church of England) and the British and Foreign School Society (non-conformist) for the education of the poor. This marked the beginning of state-funding for mainstream education in England and Wales. It also made the need for educational data more urgent as the government wanted to measure the effects of state intervention.

National surveys of schooling facilities were proposed. The new statistical societies spent large amounts of money on local surveys. While debating and waiting for the results of these initiatives, educational reformers and policymakers discovered another potential source of data: prisons. From the early 1820s, prison chaplains had been using the information on literacy contained in the prison registers to fulfil the legislative requirement to comment on the condition of prisoners in their annual reports. The number of incarcerated men and women at particular prisons who could read, read and write, or possessed neither skill began to appear in parliamentary debates on education and in reformist literature.