6 Measuring the effectiveness of the prison school

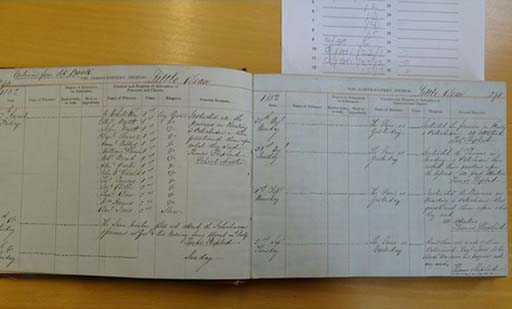

The establishment of prison schools in the early 1800s not only triggered the collection of data on prisoners’ pre-existing educational attainments. It also prompted prison authorities to develop new systems of record-keeping to monitor instruction, and it encouraged some officials to summarise the outcomes of prison education.

By the 1820s, the schoolmaster at Millbank Penitentiary was maintaining an account of the progress each prisoner was making at school in registers modelled on those in use at the Central National School (the training school run by the National Schools Society) (Holford, 1828, p. 151). In his report for 1825, the chaplain at Durham County Gaol wrote, ‘Since my last general report, 58 prisoners have attended the school, 26 of whom have been taught to read and write; the rest, who could read a little, have improved themselves in both reading and writing’ (Gaol Act Reports, 1826, p. 82).

The enthusiasm for numbers in the 1830s as a means of evaluating the effectiveness of government policy enlarged and expanded these early efforts. Prison inspector Frederic Hill encouraged local officials to record the abilities of prisoners at admission and discharge in an ‘Educational Register’. Regulations for local prisons published in 1840 and the rules for Pentonville Prison (1842) required schoolmasters and schoolmistresses to submit written reports on the conduct and progress of prisoners to the chaplain at regular intervals (Regulations for Prisons in England and Wales, 1840, rule 183; Rules for the Government of the Pentonville Prison, 1842, rule 161). Governors and surgeons also recorded data about prisoners.

From the mid-1830s, tables which summarised the outcomes of learning in prison schools began to appear in the annual reports of prison chaplains and prison inspectors. These sat alongside other numerical descriptions of the results of religious instruction – for example, the number of prisoners permitted to take Holy Communion – and the products of prisoners’ labour – from the number of boots, mats or jackets made to the quantities of stone broken in quarries for the construction of naval defences (Vincent, 2020, pp. 144–5).

Activity 4 Evaluating the results of the prison school

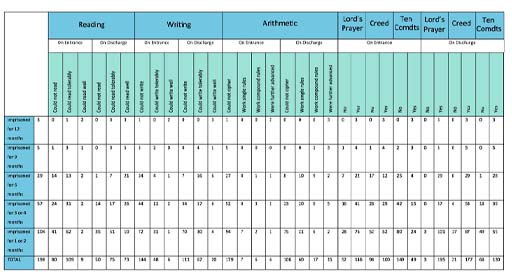

In his report on Manchester Borough Gaol published in 1851, prison inspector Herbert Voules included a table compiled by the prison chaplain which summarised the progress made by prisoners who had attended the prison school. This is reproduced below (Table 3).

- What does this table suggest is taught in the prison school? (Hint: it might be useful to know that ‘learning to cipher’ meant instruction in arithmetic.)

- Does the table suggest that prisoners make much progress in their learning? (Hint – you’ll need to compare the ‘entrance’ and ‘discharge’ columns for each area of learning.)

- According to the table, what is the single biggest factor affecting the progress of prisoners?

Access the following link to see a larger version of this table [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Discussion

- At Manchester Borough Gaol in the early 1850s, prisoners attending school were taught reading, writing and arithmetic. They were also given some religious instruction in the form of learning – or memorising – the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed and the Ten Commandments.

Overall, the progress made by prisoners during their time at school appears to have been limited, especially in the basic elements of reading, writing and arithmetic.

- Of the 80 prisoners who were unable to read on admission, 50 still could not read on discharge.

- Similarly, of the 144 prisoners who could not write, 111 were still unable to write on discharge.

- Progress in arithmetic looks slightly better. Of the 179 prisoners who could not cipher on admission, 73 acquired some level of proficiency before their discharge. Still, 106 left the prison unable to complete basic sums in addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

More progress seems to have been made in memorising key Christian texts. For example, very few – only 3 – left the prison unable to recite the Lord’s Prayer.

- According to the table, the biggest single factor which affected the progress of prisoners attending school was time.

- Very little progress was made by prisoners with sentences of one or two months. For example, only 6 of those who could not read on admission and only 2 of those who could not write on admission learned these skills by the time of their discharge. The 3 prisoners who did not learn to recite the Lord’s Prayer were all incarcerated for one or two months.

- No prisoner serving a sentence of nine or twelve months left Manchester Borough Gaol unable to read, write or cipher.

It is worthwhile comparing the results from Manchester Borough Gaol with those from Pentonville Prison published in 1847 (see Table 4). The progress made by most convicts at Pentonville was substantial, especially in arithmetic. However, these convicts had been confined at Pentonville for about 18 months, attended school there for four hours each week, had time set aside for private study, and the most illiterate received extra tuition from the schoolmasters.

| Reading | |||

| On Admission | On Removal | ||

| Read well | 432 | Read well | 823 |

| tolerably | 166 | tolerably | 129 |

| imperfectly | 220 | imperfectly | 40 |

| scarcely at all | 76 | scarcely at all | 8 |

| not at all | 106 | not at all | 0 |

| 1000 | 1000 | ||

| Writing | |||

| Write well | 240 | Write well | 521 |

| tolerably | 124 | tolerably | 316 |

| imperfectly | 192 | imperfectly | 110 |

| scarcely at all | 91 | scarcely at all | 45 |

| not at all | 353 | not at all | 8 |

| 1000 | 1000 | ||

| Arithmetic | |||

| Higher rules | 102 | Higher rules | 713 |

| All common rules | 61 | All common rules | 127 |

| To multiplication | 79 | To multiplication | 81 |

| To addition | 119 | To addition | 57 |

| Scarcely at all | 639 | Scarcely at all | 22 |

| 1000 | 1000 | ||

| General Knowledge | |||

| Considerable | 165 | Considerable | 696 |

| Some | 314 | Some | 254 |

| A little | 226 | A little | 39 |

| Scarcely any or none | 295 | Scarcely any or none | 11 |

| 1000 | 1000 | ||

It could also be argued that the categories used at Manchester Borough Gaol to describe the progress made by prisoners at school hid some of their achievements. Chaplains at other prisons provided a more granular account of progress. For example, 117 prisoners at Springfield County Gaol made progress in learning to read in 1844. Of these, only 21 learned enough to read the New Testament (about the level of reading tolerably). Of the remainder, 39 learned to read easy lessons, 22 learned to read words of one syllable, 6 learned to join letters, and 29 only learned the alphabet (Gaol Act Reports, 1845, p. 50).

Although representing progress, these skills were fragile and easily lost if not practised. In 1845, an officer at Wakefield House of Correction explained that although prisoners made considerable progress, especially in writing and arithmetic, ‘on recommittal we find they have lost the greatest part of what they had acquired in prison’ (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 11th Report, 1846, p. 42).