5 Facilities for self-instruction

In Session 4, you looked at opportunities for education outside the prison school through the provision of books and other reading matter, and increasingly through the prison library. As schools in convict prisons began to exclude men and women with basic competence in reading, writing and arithmetic, facilities for self-instruction became even more important.

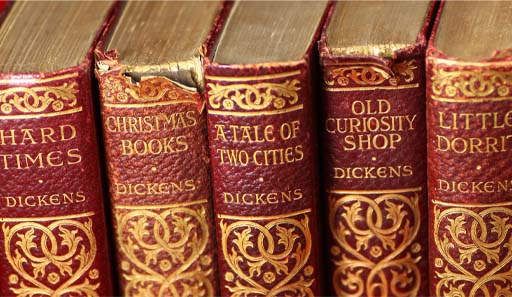

From the late 1830s, convicts at Millbank, and then Pentonville, were given a small allocation of ‘schoolbooks’ to aid private study in their cells. From 1850, male convicts arriving at public works prisons for their second stage of punishment were given two schoolbooks in addition to a library book and religious books as well as a slate and pencil to enable them to study in the evenings. At Portsmouth, for example, the men were allowed to choose two of the following works: ‘arithmetic, mensuration, book-keeping, practical geometry, Chambers’ Mathematics, dictionary, grammar, [and] spelling-book’ (Directors of Convict Prisons Report, 1854, p. 234).

Standing Order 143 – which excluded the ‘well’ and ‘tolerably’ educated from schools at public works prisons – instructed governors to supply these men ‘with the means of continuing their studies in their cells’. At Portland and Portsmouth, convicts were permitted to have additional schoolbooks in their cells. The 1863 inquiry on discipline in local prisons recommended the greater provision of artificial light in cells to facilitate evening schools and self-instruction.

Activity 4 Book purges

Standing Order 261 was sent to governors of convict prisons on 2 November 1865. Read it now, and try to answer the following questions:

- What are governors and chaplains being asked to do?

- Why do you think they are being asked to do this?

- What consequences do you think this might have for education in the prison?

Standing Order No. 261

2nd November, 1865

PRISON LIBRARIES

The yearly supply of Books for the Libraries of Convict Prisons will, in future, be limited to the replacing of those Books which become unfit for further use during the year.

Governors and Chaplains of Prisons will be good enough to remove from Prison Libraries all Novels, and Tales of an uninstructive character, and will be careful that the periodicals they demand are unobjectionable in this respect.

E. Y. W. HENDERSON [chair of the Convict Prison Directors]

Discussion

- Convict prison governors and chaplains are being asked to remove all novels and tales of an uninstructive character from the prison library. Also, they are instructed to ensure that the periodicals (journals and magazines) they request do not have uninstructive stories in them.

- The Convict Prison Directors believed that literature which simply entertained convicts was not appropriate.

- One consequence of this Standing Order was to reduce the amount of available reading matter in the prison. Another was to reduce the range of reading matter. The removal of entertaining literature made reading less appealing and so removed incentives for prisoners to learn to read, as well as opportunities to practice and improve reading skills.