6 Cellular instruction

As explained in the video for this session, the use of separation – the confinement of prisoners in individual cells and the limitation of their opportunities to be in the company of other prisoners – for reformatory purposes was increasingly challenged after 1850. However, a new generation of penal reformers reacting to the perceived threat of rising criminality and the end of transportation were attracted to the ability of separate confinement to inflict mental suffering on prisoners. Both inquiries on prison discipline in convict and local prisons recommended its use and expansion.

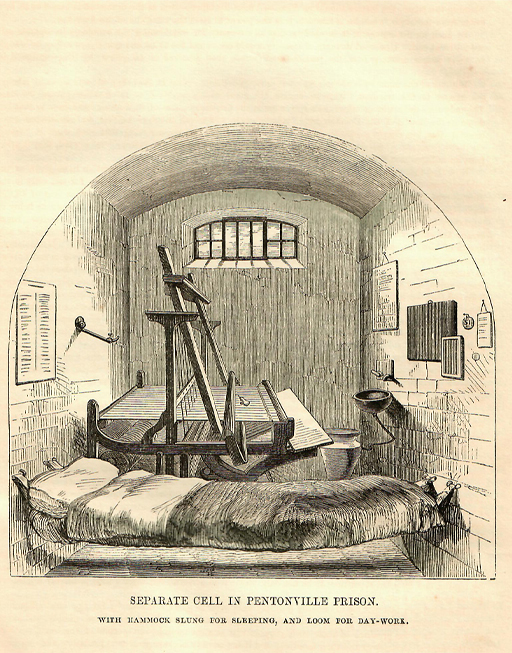

The Commissioners also recommended that in convict prisons the amount food given to those in separate confinement should be reduced for the first four months. In addition, the Convict Prison Directors installed fixed wooded beds with small coir mattresses in cells at Millbank and Pentonville, and, to render the discipline ‘still further deterrent’, introduced a system of ‘cellular instruction’ (teaching individuals in cells) to replace the practice of assembling convicts in school classes (Directors of Convict Prisons Report, 1864, p. 8).

Although cellular instruction was already in use at some local prisons before 1863, it became more widespread following the report of the inquiry into discipline in local prisons and the 1865 Prison Act. Despite this, the practice of assembling prisoners in classes for school was never entirely abolished. Male convicts in their second stage of penal servitude also continued to be assembled in classes for school.

Activity 5 Evaluating the use of cellular instruction

This activity is in two parts.

Part 1

Under the system of cellular instruction at Millbank and Pentonville, male convicts, who had formerly spent between three and six hours in classes each week, now received only fifteen minutes of individual tuition in their cells (though at Millbank, twice a week, where possible).

The following reports were written by the Rev. George de Renzi, chaplain at Millbank, and the Rev. Ambrose Sherwin, chaplain at Pentonville, after one year’s experience of cellular instruction. Although not directly involved in teaching the convicts, the chaplains supervised the schoolmasters and examined the prisoners every six months.

As you read them, consider the following questions:

- What are the advantages of cellular instruction that the two chaplains describe and are these advantages disciplinary or educational?

- Does either chaplain mention any disadvantages?

- Can you think of any disadvantages not listed?

Extract from the Annual Report of the Rev. George de Renzi, chaplain at Millbank Prison, for the year 1864

With reference to the schools, I am glad to be able to report most favourably of the system at present in operation. It is now more than 12 months since the practice, which had prevailed for many years, of assembling the men in a school-room, which has been discontinued, in lieu of which school is now held in the wards, the prisoners remaining in their cells and receiving instruction individually. […] There is no difficulty now in gaining the attention of the men, and they evince a much greater interest in their own improvement, and as a natural consequence an increased success has attended the efforts of the schoolmasters. But the more satisfactory progress of the prisoners is not the only advantage resulting from the change; it has also been attended with considerable gain to the discipline, inasmuch as, from the teaching being carried on in the cells, the evils, inseparable from the bringing together of the prisoners, are proportionately diminished.

Extract from the Annual Report of the Rev Ambrose Sherwin, chaplain at Pentonville Prison, for the year 1865

The mode of teaching the prisoners separately in their cells, instead of as heretofore in school classes, commenced in January last year. […] [We] are able to say it is better system for adults in a convict prison, for sufficient instruction is imparted in the elementary and more essential parts of secular education, viz: reading, writing and arithmetic; more individual effort on the part of the prisoner is produced, the time of the teacher is apportioned according to the wants of the more ignorant, and superfluous attention to others precluded. Then, in a moral and disciplinary point of view the wholesome effects of intercepted communication are clearly seen. It is a great help to all who really wish to withdraw from evil and to amend, and it is a great preventive of the machinations of evil-disposed men who take pleasure in corrupting others.

The plan pursued is in many ways decidedly restrictive; not only are various subjects formerly taught in the school class now necessarily laid aside, but also a much smaller amount of instruction is given to some classes than had been given; even the means of self teaching are limited, inasmuch as fewer books are allowed in the cells, and the use of paper, pens and ink is entirely superseded, expect for the half yearly purpose of writing a letter; all library books of a merely amusing character, and all tales not instructive, are eliminated from the catalogue; there is a parallelising in fact, in the retrenchment of mental redundancies and the reduced scale of dietary.

Discussion

- You might have identified the following advantages:

- In one-to-one tuition the men were not distracted by others and made more effort. Rev. de Renzi claimed that the prisoners made more progress in learning as a result. (Educational)

- Communication between prisoners during school time was eliminated. This removed the pleasure of company and the potential for corruption (the bad influence of hardened offenders on others). (Disciplinary)

- More time could be given by the teacher to those students who needed it. (Educational)

- The Rev. de Renzi does not mention any disadvantages. The Rev. Sherwin, however, highlights the restrictions on books and the ban on paper, pens and ink in cells (prisoners were given slates and pencils instead, which made learning to write more difficult, and limited their ability to use a pen when required). He implies that these restrictions combined with the reduction of the curriculum and prohibitions on entertaining books limited the potential gains of prison education.

- As for additional disadvantages, you might have thought that the reduction of time caused by one-to-one tuition – from six hours to thirty minutes each week – was a disadvantage. Also, the potential for emulation or encouragement from peers was entirely absent in a system of cellular instruction.

Part 2

Now read the following extract from the Rev Sherwin’s annual report for 1873. The chaplain has changed his mind about cellular instruction. Why? What does he now see as its disadvantages?

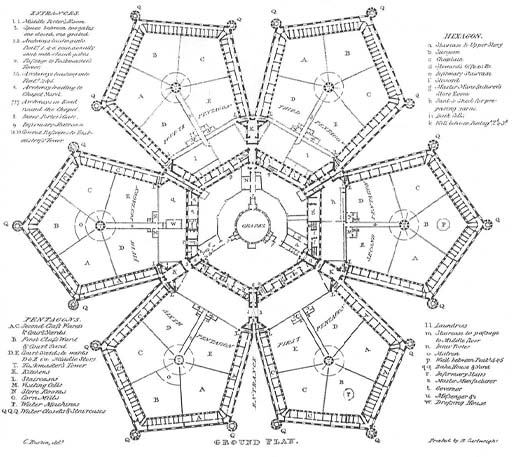

(It will be useful to know that between 1864 and 1873, the daily number of prisoners at Pentonville had increased from around 500 to almost 900, and new buildings had been erected to accommodate them.)

Extract from the Annual Report of the Rev. Ambrose Sherwin, chaplain at Pentonville Prison, for the year 1873

When some years ago class teaching was suspended and separate cellular instruction resorted to, the experiment seemed favourable in a disciplinary point of view, but then the prison was not more than half its present size and extent, it was manageable, and sufficient instruction was practicable.

Now, however, there is evidently a considerable loss of schoolmasters’ time in making the tour of the prison, and a waste of teaching power in expending upon one prisoner an amount of teaching which might suffice for the class of twenty.

Again, the effectual supervision by the Chaplain of the schoolmasters while passing from cell to cell is absolutely impossible under existing circumstances.

I would therefore respectfully suggest the expediency of reviving the class teaching of the two lower or more ignorant sections of convicts.

Discussion

The Rev. Sherwin declared that cellular instruction had become impracticable because the prison had doubled in size. As a result, valuable teaching time was wasted as schoolmasters had to walk between cells to visit those on the school roll. Also, Sherwin claimed that the amount of time spent on one prisoner could have been used to teach a whole class. Finally, Sherwin complained that it was impossible to supervise the teaching of the schoolmasters in a system of cellular instruction.

It is important not to dismiss cellular instruction as a mode of delivery outright. One-to-one tuition given in short irregular bursts was common in working-class communities in the early 1800s and assisted the early spread of literacy in British society. Convicts (and local prisoners) arrived at prison with different levels of attainment, educational experiences and capacities. It could be argued that cellular instruction provided an opportunity to tailor teaching to individual needs, but there is little evidence that this was exploited.

Instead, from the 1860s at least, cellular instruction was a disciplinary tool. It reduced the instruction that prisoners received to an almost negligible – or token – amount. As the Rev Sherwin acknowledged in a latter report, cellular instruction combined with the focus on the acquirement of the basic skills made instruction for many prisoners unpleasant and monotonous (Directors of Convict Prisons Report, 1876, p. 338).