1 The Revised Code in convict prisons

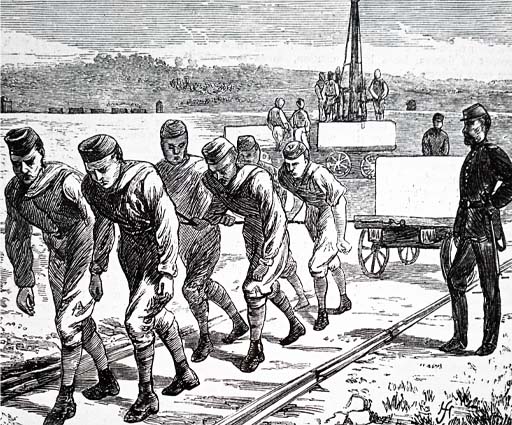

By the late 1860s, some uniformity in the delivery of education in convict prisons had been achieved. Men and women serving their first stage of penal servitude at Millbank and Pentonville were taught individually in their cells. Men in their second stage at public works prisons were taught in classes in the evening.

However, prison officials retained significant control over what convicts were taught. Different sets of lesson books were used: those of the British and Foreign Schools Society at Millbank and Pentonville, those produced by the Commissioners of Irish National Education at public works prisons, and those published by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge at Fulham (Women’s) Convict Prison.

Chaplains at public works prisons had been ordered to restrict attendance at school to uneducated men who most required assistance, but they still got to decide what degree of education justified exclusion. Just about all prisoners at Millbank and at the female convict prisons continued to attend school.

These differences in curriculum and attendance mattered, not just for reasons of fairness, but also because convicts were transferred between prisons as they progressed through the stages of their sentence. Moreover, inconsistent educational expectations meant that there was no way of measuring the effectiveness of instruction across the sector. And so, in an effort to homogenise the school curriculum in all convict prisons, on 15 May 1868, Standing Order 309 introduced a new system of examination by Standards. These were the same Standards that had been introduced in state-subsidised elementary schools by the 1862 Revised Code (which you learned about in Session 6).

Activity 1 Examinations by Standards in convict prisons

Read Standing Order 309 (link below) and consider the following questions:

- Standing Order 309 introduced examination by Standards. What else did it mandate?

- At each examination, chaplains were asked to record the Standard achieved by the convict as well as the Standard that had been achieved at his or her last examination. What other information were chaplains asked to record in a separate table?

Standing Order 309 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Source: Index to the Standing Orders, 1870, SO 309.

Discussion

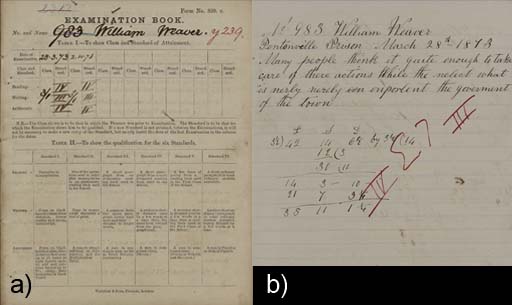

- As well as the use of Standards for the examination of convicts in reading, writing and arithmetic, Standing Order 309 also mandated the use of ‘examination books’. Every convict enrolled in school would be assigned an examination book and the results of each examination would be recorded in it. Examination books travelled with convicts as they moved between prisons. Standing Order 309 also directed chaplains (or assistant chaplains) to act as the Examiner. The chaplain was ordered to use the examination books to describe the progress made by prisoners – in numerical form – in his annual report.

- In a separate table (III), chaplains were asked to record the degree of progress which convicts had made in each subject between examinations using the following abbreviations: G.P. for Great Progress, P for Progress, S for Stationary, and B for Gone Back.

While there were six months between examinations, time spent at school was very limited, and many prisoners did not achieve a new Standard at each examination. Table III was therefore essential to measure whether any progress at all had been achieved.

Perhaps you were surprised by the grade ‘B’ or ‘Gone Back’. Often we think of learning as a linear and mostly progressive experience: that, at least while in education, skills are learned (or not) and then developed (or not). This is a good reminder of the fragility of skills at the most basic level of competence. There are many scenarios in the penal context which might mean that an individual goes backwards in their learning, for example as a result of transfer to a new prison (where less time might be given to lessons), or as a consequence of the mental strain of imprisonment (which might be felt by prisoners in separate confinement, or when performing hard labour).