6 Warders as teachers

In Session 2, you looked at the rise of the prison schoolmaster (and, to a lesser extent, the prison schoolmistress). By the 1850s, qualified schoolmasters and schoolmistresses had been appointed to deliver teaching in all convict institutions (including on hulks). Many large local prisons had also appointed schoolmasters (and some schoolmistresses) who had some teacher training or teaching experience.

Through the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, there remained a significant number of unqualified teachers and prison officers – warders, wardresses and matrons – in teaching roles. At some institutions, schoolmasters had been forced to take on warder duties when their hours of teaching were reduced (Crone, 2022).

The Fenwick Committee had been asked to consider ‘the class and qualifications of the persons to be engaged as teachers in small or large prisons, and their number and remuneration’ (‘Copy of instructions sent to each member of the Committee’, 1879). Employing an entire staff of qualified schoolmasters across all local prisons, they discovered, would be very expensive. The Home Secretary was reluctant to support such a proposal because he did not believe ‘that the teaching which can be given in short sentence prisons will do much good or will diminish crime in any degree proportionate to its cost.’ Good men, who were strong morally and capable of influencing were needed, he continued, but trained schoolmasters and schoolmistresses were unnecessary when teaching would not extend past basic literacy and numeracy (‘Report on costs of the proposed scheme’, 14 November 1879).

While schoolmasters and schoolmistress appointed before centralisation in 1878 were allowed to keep their titles and pay scales, from 1880 no more qualified teachers were appointed to the local prison service. Instead, warders and wardresses were promoted to the rank of schoolmaster-warder or schoolmistress-wardress on passing an examination under a School Board inspector. These officers were paid as warders and received an additional allowance for their teaching duties (in the case of schoolmaster-warders £12 per annum). Outside the time they were required to teach, they were expected to perform general warder duties.

In the short term, the creation of the schoolmaster-warder and schoolmistress-wardress gave rise to new tensions between teachers appointed after and those appointed before nationalisation, and between teachers in the local prisons and those in the convict prisons. The latter, in both cases, enjoyed better conditions including more pay. Many warders (and wardresses) found that their role as a teacher clashed with their role as a discipline officer, and made prison learners less receptive to their instruction.

In the long term, the use of warders and wardresses in local prisons proved to be the thin end of the wedge. In the late 1890s, the use of warders instead of trained teachers was applied to the convict sector. In the context of the expansion of increasingly specialised training for elementary school teachers in the civil sphere, the use of warders with minimal training as teachers in the penal world widened the gap between education inside and outside the prison even further. It also ensured that instruction in prisons was limited to basic literacy and numeracy (Crone, 2022).

Activity 4 Teaching staff in local prisons

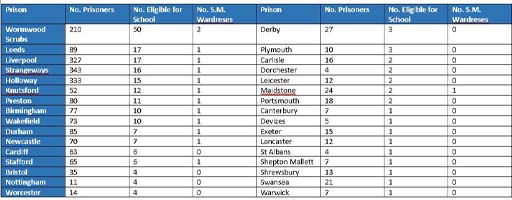

Below are two tables which show the daily average number of prisoners (male and female) enrolled in school at prisons in England and Wales in 1895. Given your knowledge of the statistics on prisoner literacy (examined in Session 5), you might be surprised by the small numbers receiving instruction. This was the consequence of the advent of national and compulsory elementary education outside the prison (fewer illiterate prisoners) and the restriction of tuition in prison to those with sentences of 4 months or more.

The tables also show how many teachers (or schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses) were employed at each prison. Look at the tables now and consider the following questions:

- Were there schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses at every prison?

- If not, why not?

- What do you think the consequences were?

Access the following link to see a larger version of this table [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Access the following link to see a larger version of this table.

Source: Mitford Committee (1896) Appendix III, p. 153.

Discussion

- Schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses were not employed at every prison. At 4 prisons with male prisoners there were no schoolmaster-warders. At 19 prisons with female prisoners there were no schoolmistress-wardresses.

- There was a relationship between the number of prisoners eligible for school and the employment of a schoolmaster-warder or schoolmistress-wardress. Especially in the case of women, if only a small number were eligible for instruction (i.e. typically 6 or fewer), no schoolmistress-wardress was appointed.

- The consequence was that some prisoners who were eligible for instruction missed out. This was especially so in the case of female prisoners. At prisons without schoolmaster-warders, sometimes the chaplain provided instruction. Rules on chaperoning at female prisons meant that this was often not possible.