8 Summary of Session 7

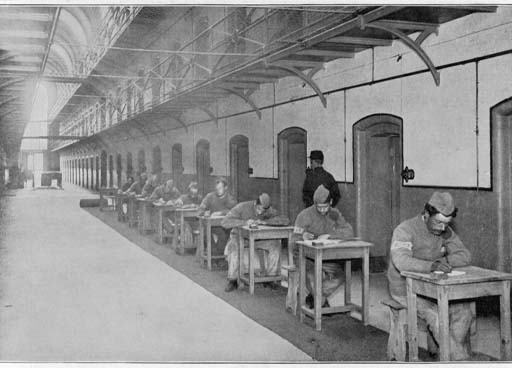

The standardisation of education for children in mainstream elementary schools through the Revised Code and the nationalisation of local prisons in 1877–78 provided penal administrators with an opportunity: to create a national system of prison education which would tackle illiteracy and innumeracy among the prison population in an equitable manner. No prisoner would receive more education than the honest labourer or than another prisoner in a different prison. Standardisation of the school curriculum in convict prisons – and especially the use of examination books – also reduced disruption to education caused by transfers between prisons.

But there were drawbacks too. While there was, nominally, a school in every UK prison, new eligibility criteria meant that in some prisons there were few, if any, prisoners enrolled in it. Uniformity relied on quantification. In local prisons, each eligible prisoner was meant to receive a set number of minutes of instruction and no more. The adoption of the Revised Code Standards in both the convict and local prison sectors reduced the task of educating prisoners to a tidy checklist of skills that could be ‘ticked off’ when achieved. Progress became more measurable, but the skills or outcomes of education that are easiest to measure are often those that are the least significant. The aim of the prison school was not to transform lives, but, by focusing exclusively on those who had failed to achieve a basic level of competence in literacy and numeracy, to correct educational deficiencies.

However, when assessing the role of prison education at this time, it is important to keep two points in view: first, that there were loopholes in Standing Orders on education which could be exploited, and so uniformity in prisons was never absolute; and second, that while acquiring the skills of reading, writing and arithmetic was not transformative in itself, these were essential tools that could aid rehabilitation if put to good use.

You should now be able to:

- assess the extent to which uniformity in prisons was achievable

- outline the impact of the pursuit of uniformity on the content and delivery of prison education

- evaluate the impact of an exclusive focus on the basic skills (reading, writing and arithmetic) on the transformative potential of education in prisons.

In the early 1890s, uniformity, and the brutal conditions of imprisonment in local and convict prisons came under attack from a new generation of penal reformers concerned about rates of re-offending and the damage that imprisonment caused to individual prisoners. In Session 8, you’ll look at the extent to which this backlash offered a new opportunity for prison education.

You can now go to Session 8 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .