4 Reforming prison education

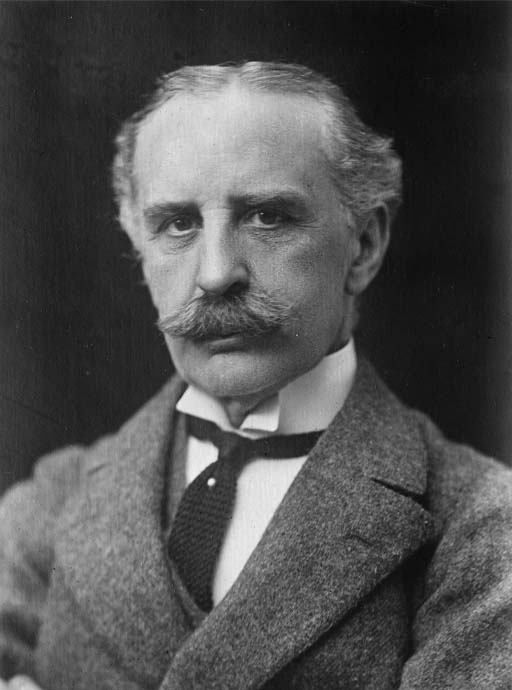

On the eve of the completion of the Gladstone Committee’s report, Edmund Du Cane retired from the chair of the English and Welsh Prison Commission. His departure was convenient, both for him (he avoided the humiliation of an official reprimand or dismissal) and for the Home Office. As Du Cane had become the ‘embodiment of prison severities’, his departure was a change in itself (McConville, 1995a, p. 607). The symbolic ‘change of guard’ was played out in Ireland too. In 1895, Charles Bourke, chair of the Prisons Board, was forced to retire (Smith, 1981, p. 337).

The new chair of the English and Welsh Prison Commission, Evelyn Ruggles-Brise, was given the task of implementing the specific recommendations of the Gladstone Committee. There were 56 in total. Ruggles-Brise proved willing to act on those which removed some of the worst features of Du Cane’s penal regime and on those which provided special treatment for certain categories of prisoners (for example, young adults and alcoholics). He was more reluctant to act on those which increased spending on prisons, or which substantially lessened the penal and deterrent aspects of imprisonment (McConville, 1995a, pp. 660–79).

Four of Gladstone’s recommendations related to the delivery of education in local and convict prisons. These included:

- the replacement of cellular instruction with class teaching

- the extension of scholarly instruction to any ‘who would be the better for it’ including those with sentences of less than four months

- the removal of discipline duties from schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses, and to take them out of uniform

- the more frequent exchange of library books.

Knowing that the implementation of these recommendations would cost money and would require some significant changes to timetables and staffing, Ruggles-Brise proposed the establishment of another departmental committee specifically to consider the provision of instruction and educational facilities in prisons.

Activity 2 The work of the Mitford Committee

Between 13 February and 17 April, the Departmental Committee on Education in Local and Convict Prisons (also known as the Mitford Committee, after its chair, Robert Mitford, prison commissioner) heard evidence from 58 witnesses. These included prison chaplains, schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses, governors, an assistant superintendent (female governor) and matron, two educational experts, William Tallack of the Howard Association (predecessor of the Howard League for Penal Reform), as well as five male and two female prisoners. The prisoners were interviewed by members of the Committee at Wormwood Scrubs Prison on 2 March 1896.

Listen to the following extracts from interviews with two male and two female prisoners at Wormwood Scrubs Prison and consider the following questions:

- What reasons did these men and women provide for their illiteracy or poor literacy and numeracy?

- Why might they have wanted to improve their literacy and numeracy while in prison?

- How authentic are these testimonies?

Transcript: Audio 1

On 2 March 1896, members of the Prisoners’ Education Committee visited Wormwood Scrubs Prison to interview male and female prisoners about their experiences of schooling while serving sentences of imprisonment. Five male and two female prisoners were interviewed. What follows are extracts from the interviews of four of the prisoners, two males (W.P. and A.B.) and two females (M.H. and K.T.).

Although several of the Committee members put questions to the prisoners, in this reconstruction they have been voiced by one person, a member of staff from The Open University. The responses given by W.P., A.B., M.H. and K.T. have been voiced by two former prisoners.

W.P. (male prisoner) called and examined

Robert Mitford (chair): How long have you been here?

W.P. (prisoner): Since 16th December.

Robert Mitford (chair): What is your sentence?

W.P. (prisoner): Eight months.

Robert Mitford (chair): You are under instruction – being taught now?

W.P. (prisoner): Not yet.

Robert Mitford (chair): Does not the schoolmaster instruct you?

W.P. (prisoner): He has come round twice.

Robert Mitford (chair): When does he come to you?

W.P. (prisoner): Thursday and today.

Robert Mitford (chair): Those are the only times?

W.P. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What are you learning now?

W.P. (prisoner): I am trying to do sums.

Robert Mitford (chair): Can you read and write?

W.P. (prisoner): I can read pretty well.

[…]

Major-General Sims: You did not do much schooling?

W.P. (prisoner): No.

Major-General Sims: How much did you do?

W.P. (prisoner): Three months altogether – the death of my mother stopped me going to school.

Mr Merrick: What age were you then?

W.P. (prisoner): Eleven.

Mr Merrick: What standard were you in when you left the school?

W.P. (prisoner): I was in the second, and they put me in the third.

Mr Merrick: Were you short in arithmetic?

W.P. (prisoner): Yes.

Mr Merrick: What use have you made of what you learned in school?

W.P. (prisoner): Forgot it all.

Mr Merrick: You never used it?

W.P. (prisoner): No.

Mr Merrick: What is the advantage of your learning now?

W.P. (prisoner): To help me when I get older.

Mr Merrick: In what way do you think?

W.P. (prisoner): I might go to work, better work.

Mr Merrick: You did not think of that before?

W.P. (prisoner): No.

[…]

Robert Mitford (chair): Have you ever been in prison before?

W.P. (prisoner): Here, last year: went out last June.

Robert Mitford (chair): What sentence did you get last year?

W.P. (prisoner): Six months.

Robert Mitford (chair): Did you learn much then?

W.P. (prisoner): I learned how to do simple multiplication.

Robert Mitford (chair): Did you remember that when you came in this time?

W.P. (prisoner): Yes.

Mr Merrick: Did you make use of it at all while you were out?

W.P. (prisoner): I was obliged to, to reckon up – I was working for the ‘Evening News’.

Mr Merrick: You found what you learned in prison enabled you to do that?

W.P. (prisoner): Yes.

[…]

A.B. (Male Prisoner) called and examined.

Robert Mitford (chair): How long have you been in here?

A.B. (prisoner): Four months.

Robert Mitford (chair): What is your sentence?

A.B. (prisoner): Five months.

Robert Mitford (chair): Are you receiving education from the schoolmaster?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes.

[…]

Robert Mitford (chair): What are you learning here?

A.B. (prisoner): Some sums and writing.

Robert Mitford (chair): What sums are you doing?

A.B. (prisoner): Addition, subtraction and money sums.

Robert Mitford (chair): Do you make any use of this when you are outside?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes, I have to work.

Robert Mitford (chair): What do you work at?

A.B. (prisoner): Costering.

Robert Mitford (chair): You find the calculations useful to you?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes.

[…]

Mr Merrick: Can you write a letter?

A.B. (prisoner): I wrote the first one here.

Major-General Sim: You are a London man?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes.

Major-General Sim: How did you miss going to school?

A.B. (prisoner): My father used to have me work.

Major-General Sim: Did the Board man try to catch you?

A.B. (prisoner): I had to work. I could earn more money at eight years old than I could now.

Mr Merrick: How old are you?

A.B. (prisoner): 24

Mr Merrick: You think what you learn in school has been of service to you?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes.

Mr Merrick: When you say you would like to learn more – what do you mean?

A.B. (prisoner): To read more difficult books.

Mr Merrick: Do you work at it every day when you have the opportunity?

A.B. (prisoner): When I have got a chance I sit down and do a little writing or reading.

Mr Merrick: You like schooling?

A.B. (prisoner): Yes.

M.H. (Female Prisoner) called and examined.

Robert Mitford (chair): How long have you been here?

M.H. (prisoner): Six months.

Robert Mitford (chair): Are you receiving instruction from the schoolmistress?

M.H. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What is she teaching you?

M.H. (prisoner): Reading and writing.

Robert Mitford (chair): Are you doing sums?

M.H. (prisoner): I am learning addition.

Robert Mitford (chair): Did you know anything when you came in here?

M.H. (prisoner): No.

[…]

Mr Merrick: Can you read a letter?

M.H. (prisoner): No.

Mr Merrick: Would you like to read and write?

M.H. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): You have letters from your mother?

M.H. (prisoner): Yes; I had one.

Robert Mitford (chair): You could not read it?

M.H. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair):Could you have done that when you first came in?

M.H. (prisoner): No; nothing when I first came in.

Mr Merrick: Can you understand it when you have read it?

M.H. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): Have you written an answer to it?

M.H. (prisoner): No, not yet. I expect to do it one day this week.

Mr Merrick: What age were you when you went to work first?

M.H. (prisoner): 15.

Mr Merrick: Did you not go to school before 15?

M.H. (prisoner): No.

Mr Merrick: Did not your mother send you?

M.H. (prisoner): No.

Mr Merrick: What did you do at home?

M.H. (prisoner): Rag-sorting.

K.T. (Female Prisoner) called and examined.

Robert Mitford (chair): How long have you been in prison?

K.T. (prisoner): Nine months.

Robert Mitford (chair): Are you receiving instruction from the schoolmistress?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What standard are you in?

K.T. (prisoner): I could not do anything when I came here; I can read and write now.

Robert Mitford (chair): You could not when you came in?

K.T. (prisoner): No; not at all.

Robert Mitford (chair): Do you belong to London?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What part of London?

K.T. (prisoner): City.

Robert Mitford (chair): How was it you never went to school?

K.T. (prisoner): I was married before I was 15, only I put down I was older?

Robert Mitford (chair): Have you ever been in prison before?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): Were you taught then?

K.T. (prisoner): No.

Robert Mitford (chair): Can you read and write now?

K.T. (prisoner): I can understand for myself.

Robert Mitford (chair): Can you understand what you read?

K.T. (prisoner): I can read a book.

Robert Mitford (chair): Can you write a letter?

K.T. (prisoner): I could to my friends.

Robert Mitford (chair): Are you glad to be taught here?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): Do you think it will be useful to you?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What do you do when you are outside?

K.T. (prisoner): Buying and selling.

Robert Mitford (chair): Do you think it will be useful to you to read and write and do sums?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Robert Mitford (chair): What do you mean by buying and selling?

K.T. (prisoner): In the market place – buying goods and selling.

Mr Merrick: What market?

K.T. (prisoner): Petticoat Lane.

Mr Merrick: Were you able to do that?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Mr Merrick: You knew whether you were being cheated or not?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Mr Merrick: Well, what would five jackets come to at one shilling six pence each?

K.T. (prisoner): (after a slight pause) seven and sixpence.

Mr Merrick: Is it reading and writing you would like to do?

K.T. (prisoner): Yes.

Discussion

- Some of the prisoners had attended school as children but had subsequently forgotten what they had learned. Others did not attend school because they had been required to work to support their families instead.

- Some of the prisoners suggested that improving their literacy and numeracy would help them in the jobs they had before imprisonment, or to obtain a better job on release. Learning to write enabled some to write a letter to loved ones outside. For some, learning to read meant that they could read letters from home and books from the library.

- It is very difficult to say how authentic these testimonies are. As with many other prisoner voices presented in this course, they are mediated through the official record. We do not know how these prisoners were selected for interview. The questions asked were leading and the answers given were short and hardly challenging.

In Session 7, you learned that between 1870 and 1880, a national system of compulsory elementary education for children aged between 5 and 10 was established in England and Wales. However, until 1891, fees still had to be paid. Even after 1891, for poorer families, sending a child to school meant that potential income needed to keep the family afloat was lost. In 1895, nearly 20% of children still did not attend school (Sutherland, 1990, pp. 142–5). Between 1870 and 1892, similar provision – universal, compulsory and free education – was made in Scotland and Ireland. In Ireland in 1900, just 62% of children were attending school regularly (Knox, n.d., pp. 2–3; Walsh, 2016, pp. 16–18).

Universal and compulsory state education did not weaken the case for prison education. If anything, it was strengthened. In their report, the Mitford Committee explained that as the state had taken responsibility for the elementary education of the population, it seemed wholly appropriate and necessary to extend provision to men and women in prison who had failed to reach the minimum educational standard expected of all citizens. However, the Committee also stressed that the provision of education in prisons must not interfere with the penal and deterrent objects of prison discipline.