5 A new scheme for prison education?

The Mitford Committee proposed the following changes to education in prisons:

- the inclusion of prisoners with sentences of three months’ imprisonment

- updates to the curriculum to reflect what was taught in state elementary schools

- a small increase in the amount of time given to teaching prisoners

- a more frequent exchange of library books

- lectures for well-behaved prisoners.

At the same time, the Committee recommended the retention of:

- cellular instruction for all except convicts working in association

- an age limit of 40 years

- the rule requiring local prisoners to complete their first stage of punishment before admission to the school

- the delivery of instruction by schoolmaster-warders and schoolmistress-wardresses.

In July 1897, the English and Welsh Prison Commissioners devised a new scheme for education in local and convict prisons based on these recommendations. The scheme also aimed to assimilate the systems in use at local and convict prisons, because convicts were now completing their first stage of penal servitude – separate confinement – in local prisons. The intention was that eligible convicts would complete their schooling during their first stage of punishment, and that schools in convict prisons would be abolished. This was never achieved in practice.

Activity 3 Evaluating the 1897 scheme for education in local prisons

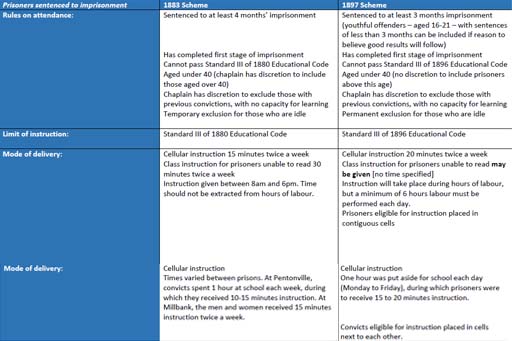

Table 1 summarises the main features of the 1897 scheme alongside those of the Fenwick scheme of 1883 (which you looked at in Session 7).

Have a look at the table now, and consider the following question: how significant were the 1897 reforms to prison education?

Access the following link to see a larger version of this table [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

Discussion

Reforms made to content and delivery of education in local and convict prisons in 1897 were modest and not all were ‘progressive’. Attendance was expanded in local prisons to include prisoners with sentences of three months’ imprisonment, or even shorter sentences in the case of young prisoners who showed promise. However, in practice, this added very few prisoners to the total eligible for instruction as most prisoners continued to receive sentences of less than three months. Prison officials were given no additional resources to provide education to young prisoners with sentences of less than three months and so were discouraged from enrolling them at school. Chaplains no longer had discretion to allow prisoners aged over 40 to receive instruction. Valuable time for instruction continued to be wasted as local prisoners had to complete their first stage of imprisonment.

The content of instruction was updated to reflect what was taught in state schools – that is, the 1896 Educational Code. The limitation of instruction to the achievement of Standard III matched the absolute minimum expected from a child on leaving compulsory education. A very small amount of additional tuition time was given to local prisoners; substantially more was given to convicts in separate confinement (as explained above, the aim was to do away with the need to provide education for convicts after their first stage of penal servitude). Cellular instruction was retained. The provision of class teaching for prisoners unable to read became optional, rather than compulsory.