6 The limits of reform

Criminologist David Garland and historians such as Martin Wiener have argued that the report of the Gladstone Committee was a watershed in penal policymaking. It provided a blueprint for a new age of ‘penal-welfarism’ (Garland, 1985, pp. 4–5; Wiener, 1990, pp. 366–79). The prison was ‘decentred’ within the broader criminal justice system as new custodial options – such as borstals (for young adult offenders), inebriate asylums (for alcoholics), and industrial schools (for children at risk of committing crime) – and non-custodial options – such as fines and probation – were increasingly used as alternatives to imprisonment. What followed was a long period, at least until the end of the Second World War, in which the prison population declined and a significant number of prisons were closed in England and Wales.

Other historians, such as Victor Bailey and Seán McConville, have argued that the significance of the Gladstone Committee report, and the changes that followed, have been over-emphasised. They highlight the fact that although some other options for dealing with convicted criminals emerged, there was very little change in the conditions and experience of imprisonment. There was a significant gap between the rhetoric of penal policy – with its emphasis on rehabilitation – and what actually went on inside prisons from the end of the 1800s through the first half of the 1900s (Bailey, 2019; McConville, 1995a, p. 696).

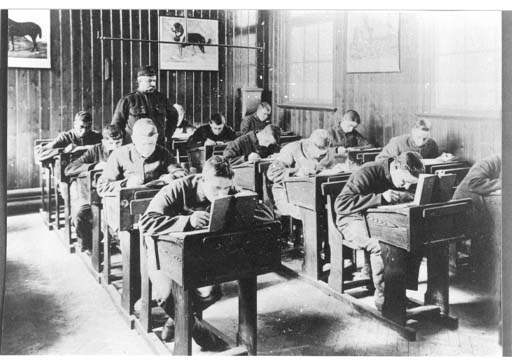

Inertia was also evident in the provision of formal instruction for prisoners, until at least the end of the First World War. The 1897 scheme offered little improvement on the Fenwick scheme of 1880. It applied to England and Wales only. Prisons in Scotland and Ireland retained schemes which had been introduced in 1883 and 1887, both of which had been based on the Fenwick scheme (see Session 7) (Smith, 1981, p. 338).

As the English and Welsh Prison Commissioners explained, to do anything more ambitious would have required more money. To extend formal education for prisoners beyond the basic skills – and beyond that which was available to the poorest, honest citizen – would have been unpalatable to the public. The basic skills fulfilled a correctional need suggested by the criminal statistics. They made the effect – and therefore value – of prison education easy to measure (Crone, 2022, ch.9).

By the end of the 1800s, as a consequence of penal and educational policy, prison education had become thoroughly embedded in the ‘modern prison’ in Britain and Ireland. Its abolition was now almost impossible. But, at the same time, the chances of its expansion into an ambitious project of social reconstruction had been severely curtailed.