4 Adapting practice to meet different cultural needs

In Session 1 you were introduced to a number of terms related to anti-racism, one of which included the notion of non-racism. To re-cap, non-racism refers to the position that many people take that seeks to ensure they are not undertaking behaviours or practices that might be seen to be discriminatory or racist. In contrast, an anti-racist approach seeks to take pro-active steps to create more inclusive environments and directly challenge practices and systems that can lead to discriminatory outcomes based around ideas of race and one’s ethnic background.

In youth sport environments, adopting a non-racist position can often inform the view that coaches and those in other support roles must treat everyone the same, because differential treatment of individuals may lead to accusations of discrimination (or discriminatory outcomes). Colour-blindness is a term that has been used to characterise this type of position, whereby seeking to treat everyone the same can ignore or downplay both the dominance of one particular set of cultural norms (that some may find easier to conform to or be part of than others) and the racial inequalities that exist in wider social life (Bonilla-Silva, 2021).

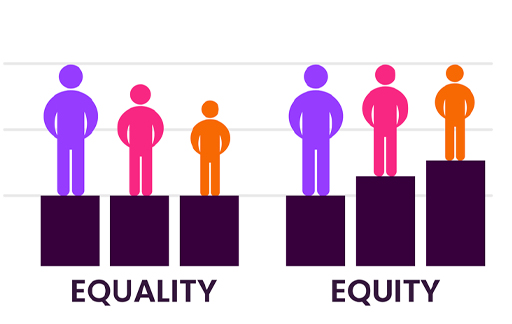

This also chimes with the different ways that people understand how social inequalities should be tackled, either through equality of treatment or through equity – a term used to describe the importance of recognising the different needs and barriers that individuals and groups of people face in life. Crucially, such differences and barriers tend to be the product of historical processes of inequality (e.g. slavery and colonialism) and contemporary systems (e.g. institutional racism) rather than being caused by the individual themselves. Figure 2 offers a useful illustration of the difference between conceptions of equality and equity.

A core pillar of anti-racist practice is to recognise that:

- people have different needs and barriers that can lead to exclusion

- this requires the adaptation of practice to ensure diverse needs can be met – so that people can feel equally included, welcomed and able to thrive.

Some examples of adapting a coach’s practice to meet the needs of an ethnically diverse group of players include:

- Ensuring that all players are able to fully observe religious festivals (i.e., reduce expectations of ‘100% attendance’ across a season).

- Being flexible around clothing and equipment requirements to ensure all cultural norms around dress are respected.

- Taking a flexible approach to time-keeping and considering when to run sessions so that they do not automatically exclude some people.

- Checking understanding of language and adapting instructions/communication as needed.

- Learning and being sensitive to cultural norms around body language/touch and expectations around social hierarchies.

Transcript

ASAD QURESHI: If a player can’t turn up for training or matches because of a religious festival, then that’s absolutely fine. I think it’s my role, probably, as the coach as well, if I have a group of players who fall into that category, and we can’t fulfill a fixture, then I need to let the league know as well. So I think it’s-- as a coach, I need to take that into account with a bit of forward planning.

Now, there’s always going to be a first time that happens, and then you learn from that, and then you know for future years. I think it’s about learning and then putting things in place going forward so that it’s not really an issue anymore. And that young person, for example, doesn’t feel awkward turning up saying, I can’t play next week because of a certain festival. So I think it’s about planning a little bit, and I think it’s about the coach being quite flexible in regards to that and understanding what’s important to that player.

Because I need to recognise if I say to that player, well, you’re going to be banned for the next game. I’m not going to play you for the game after that because of what you’ve said, then that just destroys the connection. And for that young player, the connection is around religious festival. For other players, it might be connections around other things. So I don’t want to lose that trust that I’ve built.

SULAYMAN HAFESJI-WADE: Yeah, I think it’s really important to recognise key events and key dates across the season, and how that may impact the young players that we work with. I think quite topical is the month of Ramadan, for example. And you’ve got players that are fasting, or maybe woken up early, or going to sleep a little bit later, and understanding that they may want to pray at particular moments of the day, or it might clash within the session.

So recognising that and giving an open space and an understanding that that’s OK if you’re not a part of this particular moment of the practice. That’s OK if you need a little bit of time to yourself to rest and recover, so I think that’s something that we’re quite mindful of. I also think as well, the difference is, especially on a Sunday, you have families that may want to go across to church on a Sunday, and recognising that a lot of our games are on a Sunday.

Or if there’s particular families that want to head off to a particular event at the church. Well, does a particular player only play the first three quarters of the match, so that they can head off a little bit earlier to go and spend the rest of their day travelling and getting across to the church? So just understanding again, key events, key moments within a young person’s week and day, so that we can best facilitate a programme to ensure that they can still be young people that are really committed to expressing their cultural diversity within our environment.

The next section encourages you take some time to reflect on your learning across this session.