1.5.2 Strategy 4: migration ('go away')

About 40% of the bird species that breed in Britain do not spend the winter there but migrate south, some to southern Europe, others much further afield. The swallow (Hirundo rustica), for example, may migrate as far as the Cape of southern Africa. From one perspective, migrants are European species that avoid the northern winter by migrating to a less severe environment. On the other hand, the swallow can also be regarded as an African bird that migrates to northern latitudes to breed. Why should an African bird migrate thousands of miles to breed, exposing itself to obvious risks? Swallows suffer 67% annual mortality, much of it occurring during migration. Long-distance migration also involves a huge energetic cost. The answer is that northern latitudes provide very good breeding habitats for birds. In late spring and summer these habitats support a rich food supply, in the form of seeds, fruits and insects, and there are relatively fewer herbivorous and insectivorous species living at northern latitudes, so that competition for food with which to rear their young is relatively low. Evidence for this conclusion comes from data on the clutch size of birds of the same or related species breeding at different latitudes. Temperate-breeding birds lay much larger clutches than similar species breeding at more southerly latitudes. This effect is also seen within species; for example, in the European robin (Erithacus rubecula), mean clutch size is 6.3 eggs in Scandinavia, 5.9 in central France, 4.9 in Spain, 4.2 in north Africa and 3.5 in the Canary Islands.

Birds are not the only animals that migrate. Among mammals, some populations of caribou or reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) make mass migrations of more than 1000 km, covering up to 150 km per day, in search of good grazing. Some insects also migrate over long distances. For example the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) migrates from Canada and northern USA to Mexico, flying 120 km per day. Some 30% of the monarch population, however, does not migrate but hibernates during the winter.

Migration in birds requires considerable physiological preparation. Some time before they leave, migrants increase their feeding rate and lay down fat reserves, amounting to between 20 and 50% of total body mass, depending on the species. At the top of this range are the ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris), which flies across the Gulf of Mexico, and the sedge warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), which migrates from Britain to west Africa. Both these species complete their migration in a single sustained flight. Species that carry smaller loads of fat typically fly in a series of stages, stopping to feed and put on weight along the route. The rate at which migratory birds put on weight prior to migration is remarkable. Whitethroats (Sylvia communis) preparing to migrate from Sweden increase their food intake by about 70%, their body mass increases by 7% per day, and they depart 50% heavier than normal.

Prior to migration, smaller birds build up larger fat reserves, relative to their body size, than do larger birds. This size effect is related to a measure of the amount of power that a bird can generate, called the power margin, which is defined as the difference between the maximum power than can be developed by the flight muscles and the power required for unladen (with no extra fat) level flight at a standard speed in still air. A large bird such as a swan has a small power margin, so swans need to build up speed before they can take off, and, once airborne, they climb rather slowly. Small birds, with a large power margin, can take off vertically and climb very rapidly (Hedenstrom and Alerstam, 1992). The small power margin of large migrants, such as white storks (Ciconia ciconia) which migrate from Europe to Africa and back, means that they cannot carry large amounts of fat to support long flights. They economise on fuel, to some extent, by soaring on thermals, rather than using flapping flight, but these habits constrain them to routes that do not cross the sea. Storks migrate either over Gibraltar in the west, or over Israel in the east, depending on where they breed. They also make frequent stops to feed.

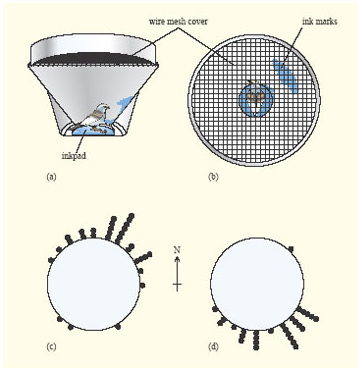

As birds put on weight prior to migration, they start to show migratory restlessness. Birds held in captivity just before the migration season do a lot of hopping about and experiments have shown that this hopping is not random, but is oriented in different directions in spring and autumn (Figure 17).

Experimental studies of captive birds have revealed that the proximate factors that stimulate increased feeding prior to migration and migratory restlessness are decreases in the L : D ratio (i.e. longer nights) and, in some species, a circannual clock.

To complete their life cycle, migratory birds make at least two journeys: outwards to the wintering site and a return journey next spring back to the breeding site. A major determinant of reproductive success for many temperate bird species is the date on which they start to breed. In the majority of species, pairs that start to breed early in the spring fledge more young. There are several reasons for this correlation, the relative importance of which varies from species to species. Firstly, early breeders generally secure better territories, in terms of the abundance of food that they contain. Secondly, an early start often means that a pair has time to produce and rear a second clutch in the same season. Thirdly, in some species the earlier breeders are better synchronised with their environment, such that the time of peak food requirement (i.e. during feeding of the young) is synchronised with the time of maximum food availability.

A recent study of the American redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), suggests that a further factor could be important. It was found that the earliest birds to arrive at breeding sites were in better condition than later birds, some of which arrived up to a month later. This study investigated the tropical wintering habitat of this species and found that the early-arriving, good-condition birds had wintered in better habitats than later arrivers. This study therefore suggests that the quality of winter habitats may be an important determinant of fitness for migratory birds. It also reinforces the point that, in considering the success of organisms, it is important to consider all parts of their life cycle.