1.2 Satellite systems and their origins

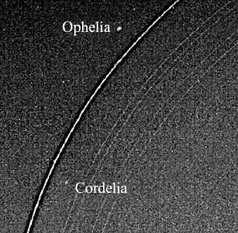

The satellite systems of the giant planets have several features in common. Most satellites are in synchronous rotation, always keeping the same face towards their planet. Irregularly shaped moonlets associated with the ring system orbit closest to the planet. They travel in near-circular prograde orbits in the planet's equatorial plane. ('Prograde' in this sense means orbiting in the same direction as the planet's spin.) These moonlets (like the rings) are believed to be fragments of larger satellites that were destroyed by collisions or tidal forces (Figures 4 and 5). Most are bright and presumed to be icy in composition.

Orbiting further from each planet come all the satellites large enough to be spherical (or nearly so) in shape, typically in near-circular prograde orbits close to the planet's equatorial plane. These satellites probably grew within a disc of gas and dust that surrounded the planet in the later stages of its growth, mimicking in miniature the birth of the terrestrial planets from the solar nebula. Neptune's large satellite, Triton, is an exception (Figure 6). This has a retrograde orbit, and may be a Pluto-like Kuiper Belt object that was captured into orbit around Neptune some billions of years ago. (We have used the term 'Kuiper Belt' but you may also see it called the 'Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt'. Kenneth Edgeworth, a British astronomer, published similar ideas a few years prior to Kuiper, but this only really came to light after the term 'Kuiper Belt' had become widely established.)

Beyond its large satellites each giant planet has a second collection of small irregular-shaped satellites, travelling in elongated, inclined and in many cases retrograde orbits. Most are dark bodies, rich in silicates and/or carbon compounds. These satellites are likely to be captured comets or asteroids (Figure 7).