3.4 The Icy Worlds: A Planetary Protection Case Study

All of the giant planets have satellites, and some of them are large enough that they have been observed since the days of astronomer Galileo Galilei who observed satellites of Jupiter in the 1600s (these are known as the Galilean satellites Io, Europe, Ganymede and Callisto). However, relatively little was known about them until the advent of space exploration in the 20th century. Before that, telescope observations could determine their orbits, and small changes to these allowed estimations to be made of their masses. Surprisingly, some of them were less dense than would be expected from their size if they were composed entirely of solid rock (like our own Moon).

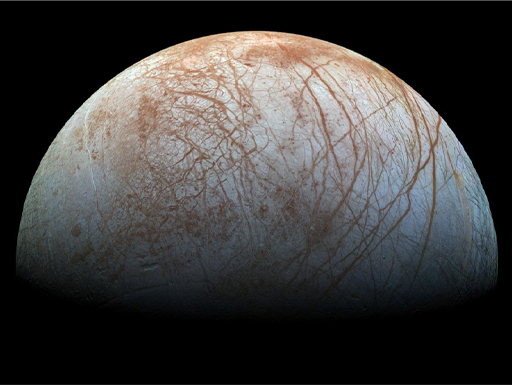

Some of this difference can be accounted for by the presence of an outer layer of ice, with Europa’s icy shroud discovered by astronomers in the 1950s (Figure 20). It is now known that several of the satellites of the outer planets have an icy surface, but the ice is not necessarily frozen water. In the outer Solar System, although water is usually the dominant component, ice can incorporate other frozen volatile molecules such as ammonia (NH3), carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4) and nitrogen (N2).

With this discovery came the possibility that there could be water on these icy worlds, and with it a focus for astrobiological studies.