2 Bird migration

The remarkable migratory behaviours of some bird species provide excellent experimental systems for studying the underlying processes, and the results have a much wider application to the study of migration than just bird behaviour. Studies on genetics, the influence of magnetic fields and physiological processes behind homeostasis illustrate general principles, but as birds have attracted so much scientific attention, they provide some of the best examples of migration studies.

Although migration is widespread amongst bird species, not all species are migratory and in some species, not all populations of the same species migrate and sometimes not all members of a population migrate. For example, in many regions, including the British Isles, some populations of birds are residents all year round and do not migrate. Other populations exhibit partial migration, where some individuals of the population in the same breeding areas remain all year round while others migrate to overwinter elsewhere..

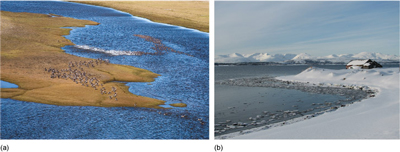

Migration occurs to some degree in most bird species that live in seasonal environments. It is prevalent because in such environments (e.g. the Arctic tundra) food supplies vary markedly throughout the year, changing from abundance during the summer to scarcity during the winter (Figure 6).

Generally speaking, birds time their migrations so that they are present in breeding areas during periods of food abundance and are absent during periods of scarcity.

In lowland tropical forests, where food supplies remain stable throughout the year, many birds that breed there remain all year. However, these forests also receive a seasonal influx of other bird species from higher latitudes which migrate from colder regions for the winter.

This means that worldwide, up to half of the 10 000 or so species of birds, totalling about five billion individuals, are thought to migrate every year on return journeys between breeding and non-breeding areas.

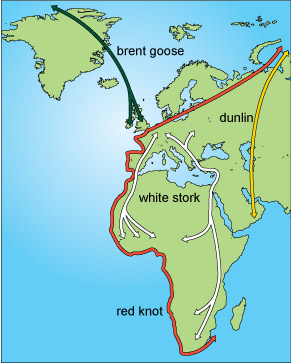

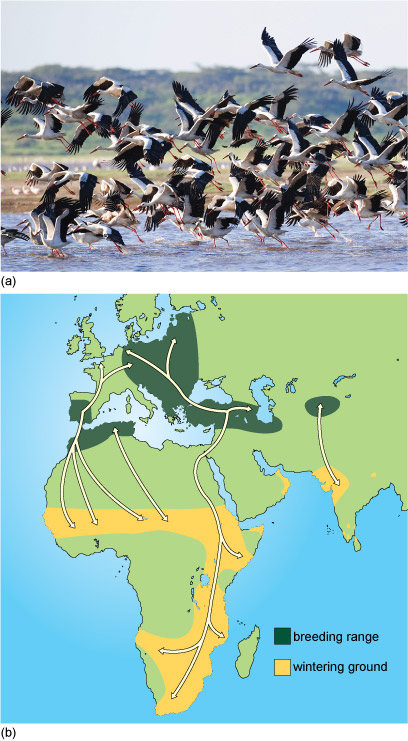

Because migration is between warm and cool habitats, birds move mainly on a north-south axis. Some, however, have an easterly or westerly component to their movements, especially those that breed in the central areas of the northern landmasses and move to the warmer edges for winter. Figure 7 shows some examples of different migration routes used by birds.

The patterns of bird migration are very diverse. Passerines are perching birds (Figure 8). They make up almost half of all bird species and some of the small passerines travel at night.

The mass migration of large storks is a spectacular sight during daylight (Figure 9).

In contrast, individuals of some species travel alone.

When the routes taken by migrating birds are plotted on a map, many long-distance migration routes are found to be clustered together, as the next section describes.