1 Rationale for expert evidence

There is an important principle in law that witnesses are not allowed to say what they thought about the evidence. What a witness thinks about the evidence is sometimes called ‘opinion’ evidence. Rather, witnesses limited to giving evidence of what they themselves directly perceived. However, expert evidence is an exception to this principle, and this section explains why.

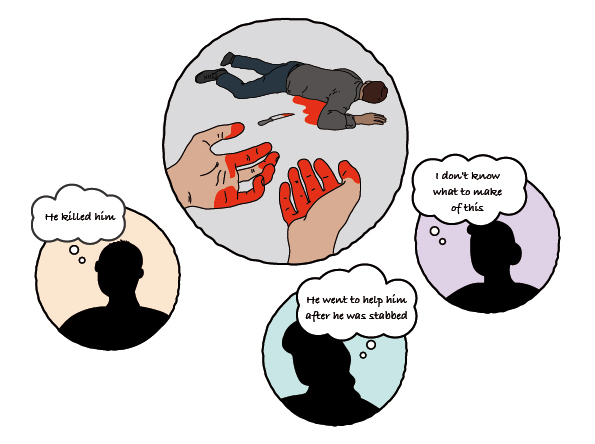

To understand why expert evidence is an exception to the rule against opinion evidence, it helps to first understand what opinion evidence is and why it can be problematic. Another term for an opinion in this context is ‘an inference’. An inference is where a person makes a mental leap from the evidence to a further fact using tacit information that is personal to them. For example, if in a stabbing case a suspect is later found with the victim’s blood on his hands, one juror might infer that the suspect was responsible for the assault. But another juror might infer that the suspect only went to help the victim after somebody else stabbed the victim. A third juror might infer something else entirely. This explains why these inferences are called ‘opinions’: the facts that are inferred from the evidence are often uncertain and may vary from person to person, as illustrated by Figure 3.

The uncertain nature of inferences from evidence explains why so-called opinion evidence is generally not admissible. Court proceedings, whether criminal or civil, can have serious consequences for those involved. It is a great responsibility to be the decision maker as a judge or juror, and it is considered important that the decision is that of the individual or individuals assigned to decide the case, not that of a third party who is otherwise unaccountable. As a result, it is the opinion of the decision makers in the case (the judge or jurors) that matters, not the opinions of third parties.

However, there are circumstances where a lay decision maker will not have an opinion on particular evidence. For example, what would a lay decision maker who is unfamiliar with fingerprint evidence make of the evidence of a particular pattern of lines and ridges? Without relevant expertise, the decision maker might be unable to make any inference at all, or the inferences that they make might be very unreliable. Without assistance, a miscarriage of justice might occur. It is to overcome this problem that exceptions are made to allow suitably qualified experts to offer their opinions to the decision maker to help them make the right decision. That leaves an uneasy balance between the expert providing help to the decision maker without influencing them so much that the expert effectively becomes the decision maker. The law of expert evidence tries to navigate this delicate balance.