What is Europe?

1 Europe in the twenty-first century

Europe is changing, but so is the way in which it is governed. The beginning of the twenty-first century sees a new Europe emerging that is in many ways different from that which previously existed. Europe is less divided than it has been for most of its history, and certainly less than it was for the war-torn first half of the twentieth century or most of the ideologically divided decades of the second half. It is incomparably richer than at any other stage of its development, and seems to enjoy unparalleled prospects for concerted growth and harmonious economic development. Nevertheless, the nature of this new Europe remains ambiguous, its mode of governance uncertain, and the views taken of its future development highly contested.

Two main complex paths of development led to the emergence of this new Europe. One was reflected in the reinvigorated, dynamic and increasingly confident European Community of the 1980s. This powerful vision of a modern, autonomous and more intensively governed Western Europe was formally drawn up in the Maastricht Treaty of 1991 (signed in 1992). Ambitious plans for further integration were adopted, and far-reaching proposals endorsed to expand the association beyond the 334 million people it currently embraced.

At the same time, another vision of Europe emerged with the sudden lifting of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and the abrupt ending of communist rule in the former satellite countries of the Soviet Union. The eyes of these countries were firmly fixed on the autonomous and strikingly dynamic social and economic community that had been constructed in the West, which seemed to offer hopes of a shared European future. There were also powerful, if more distant and abstract, conceptions of a common European heritage in terms of culture, religion and far-reaching historical links. It opened up perspectives on a broader Europe of a less well-defined character, but at least one that was unconstrained by structures of superpower control. The independence of the reconstructed eastern Europe and the severing of Russian links throughout the area was confirmed with the dissolution of the Soviet Union a couple of weeks after the Maastricht meeting. The newly independent eastern countries constituted a major community in their own right and, excluding Russia, contained 213 million people. Much of Russia's population (about 120 million people) lived in its European territory – and, at 333 million, this gave post-communist Europe a population virtually identical with that of the Maastricht countries.

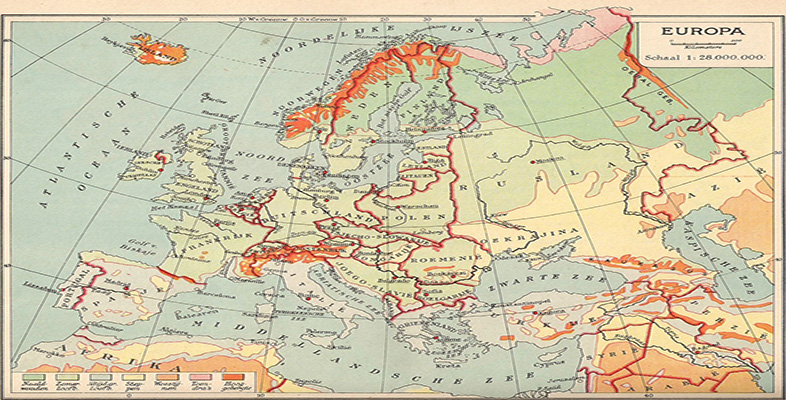

Prospects of an enlarged core Europe and one more fully integrated on a continental basis emerged with two further decisions. One was the commitment made in 1997 to incorporate some of the post-communist countries into the European mainstream and begin the process that led to eight post-communist countries joining the European Union in 2004. (See Figure 2.) The second arose from the objective endorsed at Maastricht of closer integration through eventual monetary union and the birth of a European Single Currency (ESC) in 1999. Both of these developments took place against a background of considerable conflict and growing doubt and uncertainty about the nature of the Europe that was in prospect.

In the early 1990s the economic impetus underlying the developments of the previous decade within the EU was considerably weakened (Dinan, 1994, pp. 15 7–8). Added to this downturn were the enormous costs of German unification and the pressure this exerted on the country's economy. The process of further economic integration soon began to seem considerably more problematic than had appeared at the outset. In 1999 the entire European Commission resigned amid charges of incompetence and corruption. Relations between Germany and France, the two major players in the EU, continued to evolve and seemed to lose their former balance; the implications of this change had been sharpened by the death of former French President Francois Mitterand and the retirement of Chancellor Helmut Kohl in Germany. The generation of leaders with personal memories of the decisive military conflict that ultimately forged closer European relations had now passed. In the former communist region the more advanced countries continued to grow closer to the West, but others showed few signs of democratic development or economic growth – and in some cases, such as the former Yugoslavia and southern Russia, fell into open conflict, thereby putting the whole idea of overall stable European development in a more precarious light.

Any idea of an inclusive new Europe created on the basis of events after 1989, therefore, also contains its own conflicts and contradictions, and major tensions can be detected in any model of contemporary European development. If not in terms of overt conflict (at least for the west-central core of the European area), Europe as an idea, a sphere of governance, and a model for development, continues to be driven by contradictions and contrasting expectations. Two kinds of issues arise:

-

the precise nature of the new forms of European organisation and governance that are being proposed, and how those already established actually function at the beginning of the twenty-first century;

-

more established questions of what is being referred to in any discussion of Europe itself, and the concept of Europe as a whole.

The second issue points to the broad historical processes that underlie contemporary European dilemmas and the particular questions they raise. Inherent in the contemporary conflicts and ongoing debates about the character of the region are different understandings of Europe and contrasting conceptions of what being European involves. They throw light on the context in which a new Europe has emerged and the nature of the influences that bear upon it. This course is designed to explore that wider context, its implications for contemporary processes of European development, as well as the nature of the new Europe that has emerged and the principles on which it is organised.

Your work on these issues begins with a supplementary reading. It is a classic statement on the nature of modern Europe. The short extract by Hugh Seton-Watson raises two basic questions. What is Europe? Where is Europe? Professor Seton-Watson was an eminent historian and directed the London School of Slavonic and East European Studies; thus he approaches European issues from the vantage point of the east, paying particular attention to the ambiguous role of Russia. His discussion touches four major tensions in European developments and the contrasts that continue to play a leading part in contemporary Europe. They emerge as major themes in the course as a whole, and can be summed up in terms of:

-

unity and diversity,

-

consensus and conflict,

-

transformation and tradition,

-

inclusion and exclusion.

Activity 1

Click to view ‘What is Europe, Where is Europe?’ (Reading A) by Hugh Seton-Watson [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Do not worry about some of the names and places he mentions with which you might not be familiar, but see if you can identify:

-

the basic line of argument he is pursuing;

-

how he treats the four contrasts listed above in his account of modern Europe;

-

the answers he provides to the questions in the title – what Europe is and where its boundaries lie.

How far do Seton-Watson's views correspond with your ideas?

One vision of Europe directs particular attention to cultural unity, how it came to flower towards the end of the nineteenth century, and its degeneration into nationalist fanaticism, unlimited class hatred and the blood-bath of the twentieth. Cultural unity is thus counterposed not just to diversity or disunity but to extremes of conflict on a military and class base. After 1945, though, a new European consensus began to emerge in response to the awareness of a common Soviet threat and American encouragement of European unity, in reaction to ‘the destructive nationalism of the Age of Fascism’, and to facilitate economic recovery and further material progress. But it is the cultural underpinnings of European unity, in Seton-Watson's (1985) view, that take precedence over the administrative incrementalism of the EU bureaucrats. He noted the importance for Europe of the ‘infidels beyond the Lubeck-Trieste line’ (by which he means the central and east Europeans then subject to communist rule beyond the Iron Curtain), and emphasised that they should not be neglected nor the idea of a broader Europe lost sight of.

The disappearance of the Iron Curtain four years after this article was published casts the issue of European unity in a different light and raises questions about the relationship between different parts of Europe. Europe has thus undergone a further major transformation since Seton-Watson wrote the article, and much of European history has been characterised by far-reaching and relatively rapid change. But elements of continuity and tradition have not been lacking, and they figure prominently in contemporary debates over Europe in Britain and elsewhere. Seton-Watson's stress on the role of European cultural unity, and its particular appeal both to the citizens of the defeated fascist states and the inhabitants of the then communist countries, also suggest that solidly established European traditions have carried enormous influence in twentieth-century Europe. His sceptical comments about the Brussels Eurocrats also reinforce the conviction that a properly European identity has to be based on a principle of inclusion rather than the acceptance of practices of exclusion, such as those that once wrote off Christians living under Muslim rule (referring to the Ottoman rule in much of the Balkans, which only ended in the early twentieth century) or, more recently, those that consigned much of central and eastern Europe to communist rule.

These different themes are, of course, intimately related and the further transformation of central and eastern Europe that began with the collapse of communist rule in the period 1989–1991 opens up radically new perspectives on the possibility of a more inclusive Europe. Such recent developments have, I think, definitely reinforced Seton-Watson's view of what ‘Europe’ really is – a conclusion that is, of course, inseparably bound up with what Europe should be. His preference for the cultural unity of a more traditional Europe and a broad inclusiveness also emerges quite clearly, as does his lack of enthusiasm for the politique of the Brussels Eurocrats. His answer to where Europe is remains quite vague, although it is quite clearly not just restricted to ‘the west’. These are questions that we shall now go on to examine in more detail.