“It can be terribly lonely in this journey of advocacy…”

That simple yet undeniable sentiment leapt off the screen as Mel and I combed through responses to the survey we had written to gather data for our book, Mothering at the Margins: Black Mothers Raising Autistic Children in the UK. In that moment, we knew that what had started as a ‘collective autoethnography’ (a co-constructed narrative detailing our own shared experiences) had come to represent an invaluable opportunity to amplify and validate the journeys of women like us: ‘othered mothers’ struggling to advocate for their children, while managing overlapping forms of oppression linked with gender, race and disability (Malcolm and Green, 2025).

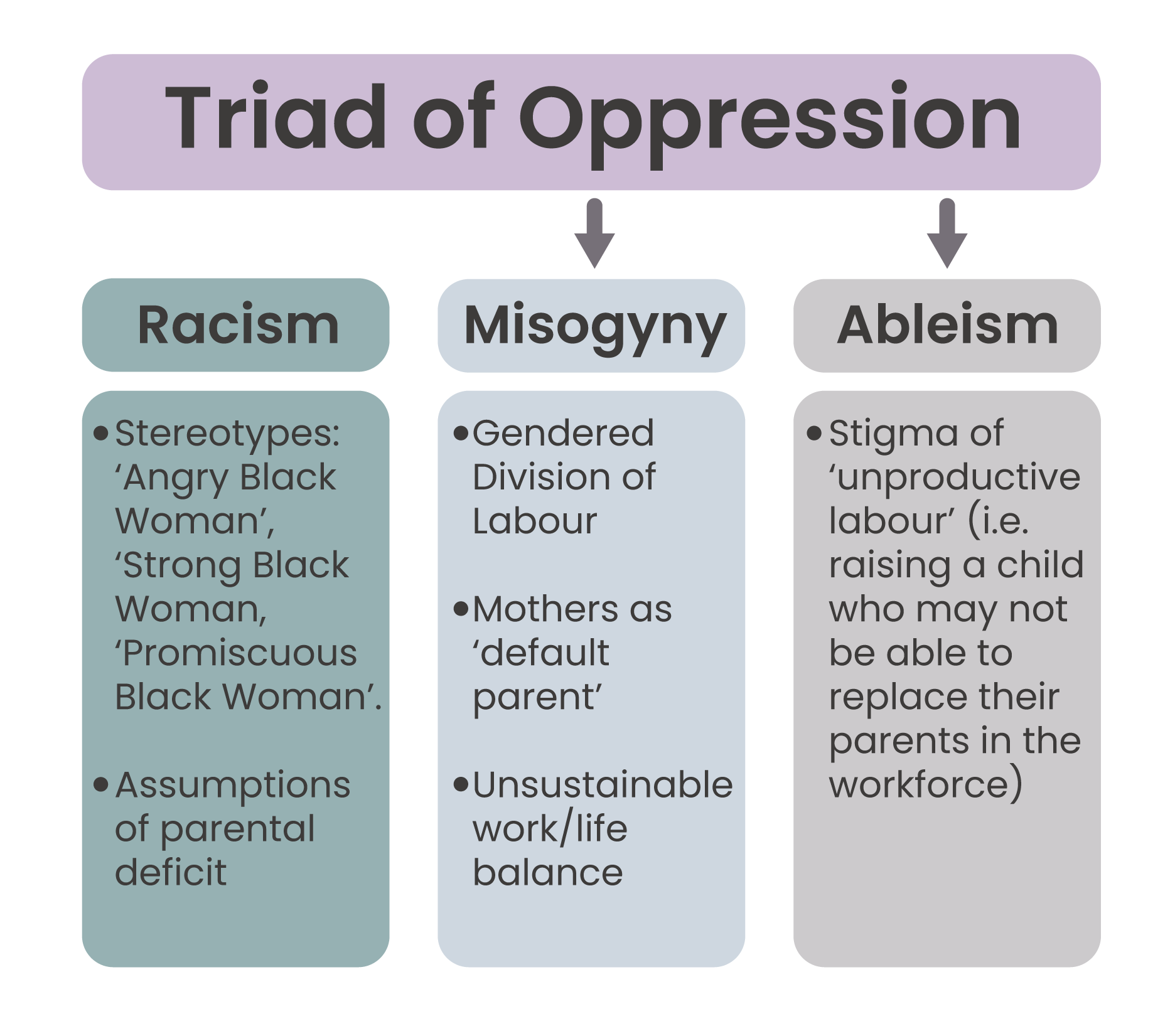

The Triad of Oppression

In our early conversations, born out of the informality and authenticity of friendship, we had distilled our research interests into a deceptively straightforward question: ‘what is it like to be a Black mother raising an autistic child in the UK’? At its core, this is a query rooted in intersectionality. From our own experiences, we knew that the challenges facing any parent-advocate are relentless and manifold, but we also had a sense of how they are potentially exacerbated by the gendered division of labour and the experience of racial discrimination. We termed this ‘the triad of oppression’.

Figure 1 Outlining the Triad of Oppression

Figure 1 Outlining the Triad of Oppression

Our Participant Research

Mel and I had already identified extensive commonalities in our own lived experiences but, ‘conscious that coincidence is not causation’ we chose to seek out other Black mothers of autistic children to contribute to the research (Malcolm and Green, 2025, p. 87). Through the aforementioned anonymised quantitative survey, nine semi-structured individual interviews, and two focus groups (each consisting of three participants), we invited Black mothers to reflect on their encounters with the healthcare, education and social care professionals involved in the lives of their autistic children. This included:

- struggles to secure a diagnosis

- challenges associated with accessing (specialised) education provision

- securing opportunities for socialisation and self-care (for both mother and child)

- managing the financial consequences of caregiving

- and planning for the practical and emotional implications of an uncertain future for a child who may, or may not, be able to live independently in adulthood.

Common experiences of Black mothers of autistic children

Specifically, in the case of Black mothers, these already overwhelming demands were found to be consolidated by the impact of racist stereotypes and assumptions of parental deficit, promiscuity and irresponsibility, with Black women and their families falsely characterised as disengaged and ‘hard to reach’. Those who actively pushed through such perceptions to advocate for their children, even in the face of structural barriers, found their tenacity mischaracterised as ‘aggression’, and there were consistent accounts of Black children being given less latitude and understanding for their ‘autistic traits’ and associated behaviours, when compared with their White autistic peers. One indicative example was that of a Black mother (Toni) who was told by a teacher that her then 6-year-old son was ‘a potential gangleader’ (Malcolm and Green, 2025, p. 145). For Black mothers who are already all too aware of the over-representation of Black neurodivergent boys and young men in the ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ such racially charged language is nothing short of devastating.

In addition, mothers detailed strategies they used to ‘disguise’ their Blackness by (at least in the case of those with sufficiently ‘White-sounding’ names), communicating with professionals exclusively via telephone or email. Black mothers raising children alongside White partners gave examples of ‘deputising’ their co-parent to represent the family, since they had found that this tended to result in more favourable outcomes. Equally, mothers who found that their intuition and expertise were frequently dismissed during appointments for their children shared that they had learned to draw attention to their own professional qualifications (as, for example, SEND teachers, speech therapists and social workers) in hopes that ‘credentialising’ themselves in this way would result in them being taken more seriously and increase the chances of securing much-needed resource for their families. Indeed, three of the nine interviewees stated that they had retrained as SEND specialists in order to compensate for the lack of support available for their children and yet even this had not been enough to help them circumnavigate the many barriers to appropriate provision.

Key themes that emerged from this ‘tapestry of Black women’s voices’ (Malcolm and Green, 2025, p. 106), including our own, were:

- guilt at not being able to advocate more effectively for one’s child

- gaslighting as attempts to highlight the impact of race and racism were routinely denied or diminished by professionals

- and the sense of a constant fight against systems which seemed designed to gatekeep resources and undermine parental expertise.

As one participant (Linda) put it when asked to identify the most significant challenge she faces in raising her autistic son, ‘I think it’s definitely the fighting with professionals… trying to advocate for your child. Get your child what they need. Constantly checking people are still doing what they’re supposed to be doing […] It’s a lot mentally’ (Malcolm and Green, 2025, p. 188).

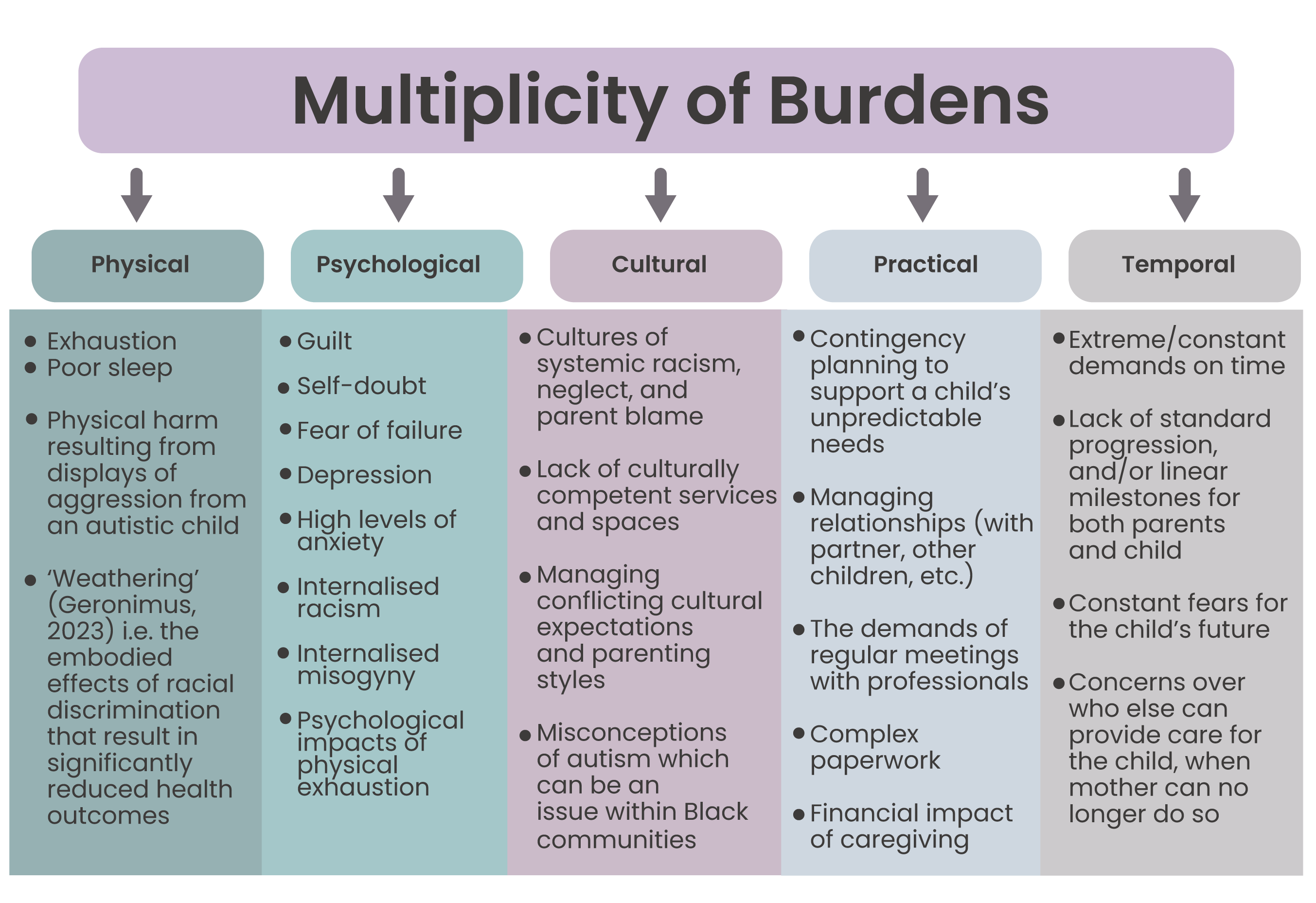

The Multiplicity of Burdens

Our research identified this increased mental load as being one of several ‘burdens’ borne by Black mothers of autistic children. As detailed in the book, the word ‘burden’ is used advisedly to speak to the consequences of marginalisation and oppression, and the debilitating effects in which they result. It is not intended as a label for the children themselves, who are anything but burdensome in the eyes of the mothers who advocate for them. Rather, it is the ‘triad of oppression’ which gives rise to the ‘multiplicity of burdens’, the impact of which is detailed in the diagram below.

Figure 2 Unpacking the Multiplicity of Burdens

Figure 2 Unpacking the Multiplicity of Burdens

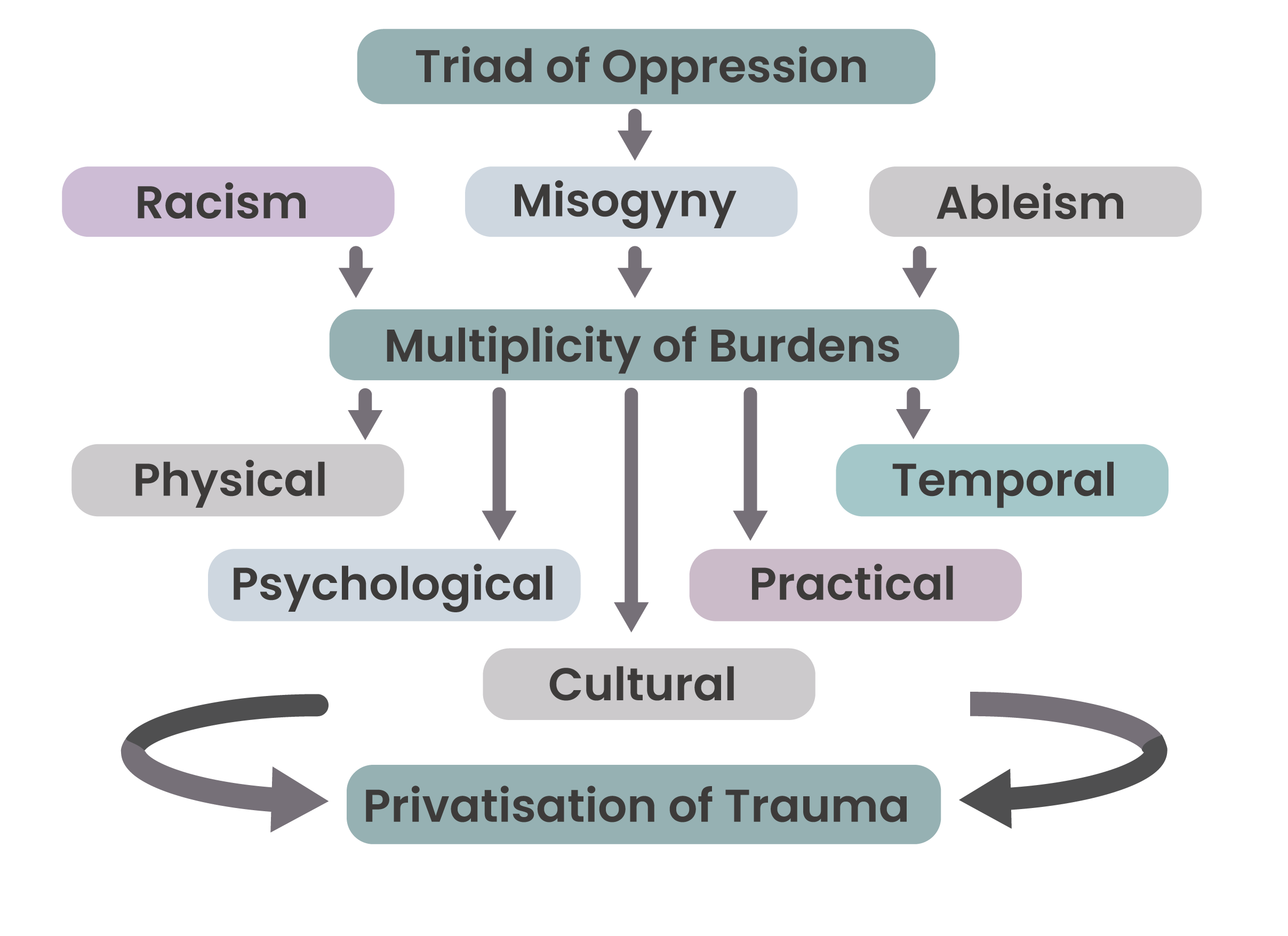

The Privatisation of Trauma

The accounts provided by our research participants illustrated that Black mothers of autistic children contend with an unsustainable combination of demand which results in observable physical and psychological harms. However, beyond the work that we ourselves have undertaken, there is vanishingly little research which focuses specifically on Black motherhood and disability. By extension, there is an alarming lack of culturally competent provision to support mothers whose identity sits at the intersection of race, gender, and disability.

This ensures that, in many cases, the challenges associated with the ‘multiplicity of burdens’ are borne in silence and isolation. Tropes of ‘strength’ and ‘resilience’, far from empowering Black mothers of autistic children, function to normalise and minimise this avoidable suffering, in a process which we have termed the ‘privatisation of trauma’.

Figure 3 How the Multiplicity of Burdens leads to the Privatisation of Trauma

Figure 3 How the Multiplicity of Burdens leads to the Privatisation of Trauma

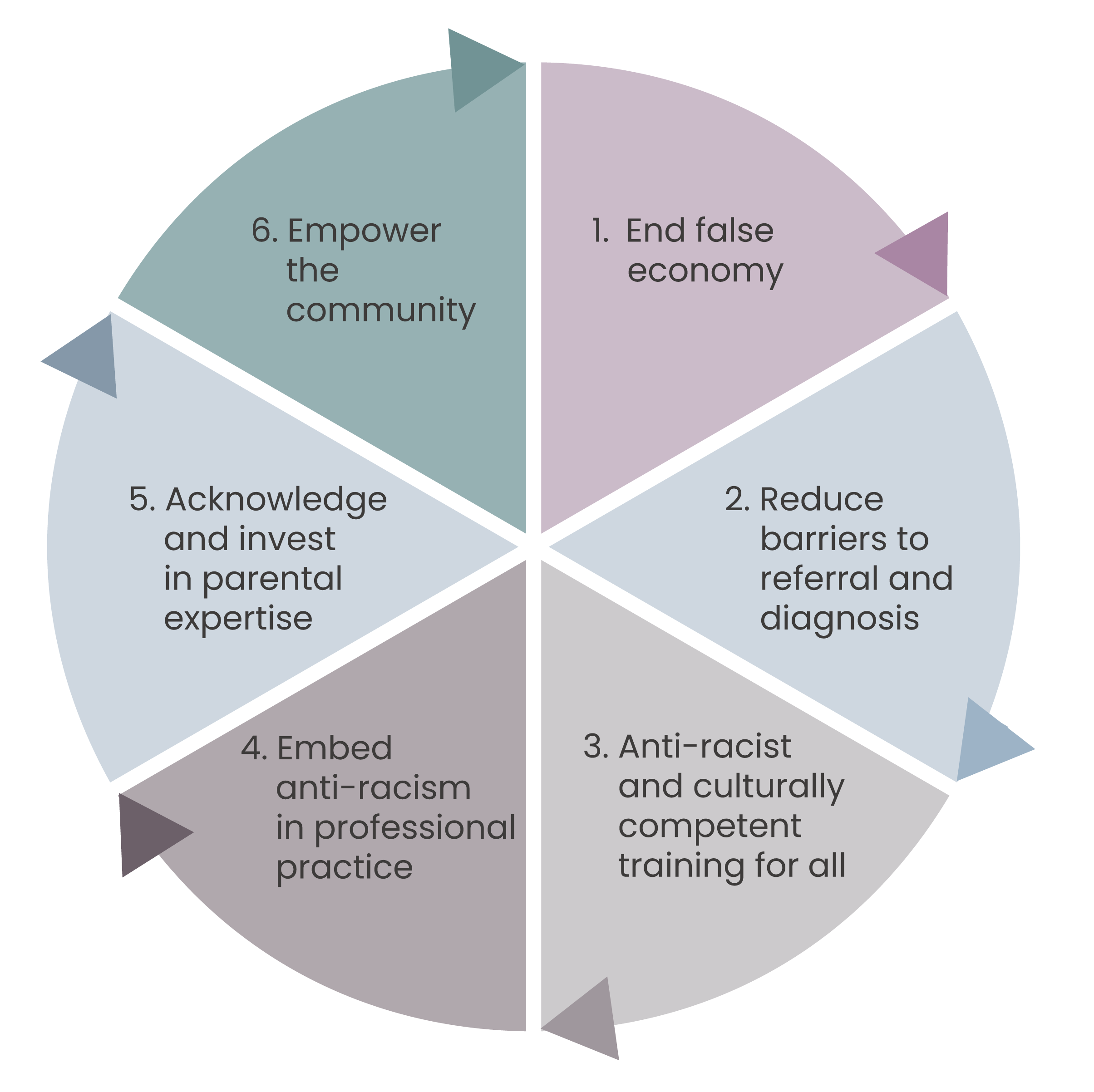

A Transformative Agenda

When we recruited participants for our research, Mel and I made a promise both to each other and to our fellow ‘othered mothers’ that in sharing our stories we would seek to build a ‘community of resistance’ focused on meaningful transformation of a broken system (Malcolm and Green, 2025, p. 15). It is not sufficient to highlight the challenges faced by Black mothers of autistic children; our work also takes aim at systemic change that can alleviate the impact of the ‘multiplicity of burdens’. The resulting recommendations are as follows:

Figure 4 Recommendations for improved professional practice

Figure 4 Recommendations for improved professional practice

An end to false economy: ill-conceived cuts to key disability support services generate long-term financial and social crises, the consequences of which are borne disproportionately by marginalised groups. Only investment can improve outcomes and reduce costs.

Reduce the number of barriers to referral and diagnosis: Diagnostic delays reflect and reinforce racial biases, and exacerbate the struggles faced by Black mothers and their autistic children.

Anti-racist and culturally competent training for all: Comprehensive, mandatory training designed by those with lived experience is essential to creating a neuro-affirming and culturally competent, fair and effective SEND system.

Embed anti-racism into professional practice: Representation through inclusive hiring matters, but it is not enough. Professionals must be trained in anti-racism, and services must be responsive to the lived experiences of racially minoritised families.

Acknowledge and invest in parental expertise: True systemic change requires professionals collaborating with parents, rather than assuming parental deficit.

Empower the community: Black mothers raising autistic children have identified the need for a locally based Wellbeing and Advocacy Hub, a One-Stop Shop, for culturally competent support, professional services, and peer-led guidance. Initiatives that centre community expertise and create holistic, empowering spaces can alleviate systemic burdens, reduce isolation, and foster meaningful, lasting change.

Summary

Raising an autistic child in an increasingly hostile social and economic climate is enormously challenging for any parent, especially in the context of ongoing cuts to disability support services. However, our research has demonstrated that intersecting forms of oppression faced by Black mothers consolidate and significantly exacerbate such struggles. This is why ‘Mothering at the Margins’ calls on researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to acknowledge the human cost of the ‘multiplicity of burdens’ and to prioritise anti-racist and culturally competent services which can offer tailored support for this uniquely, and needlessly, marginalised group of caregivers.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews