4.5 Learning in different context: forest school and refugee camp

In the next activity you will see two contrasting examples of primary education.

Activity 11

Read the introductions about the two interviewees before watching the slideshows and listening to their comments about teaching and the learning in their schools. As you read, watch and listen, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you think what each school offers to the children is appropriate? Why or why not?

- Thinking back to the activities on quality education and learner-centered education, what would you identify as elements of ‘quality’ and ‘learner centeredness’ in each of these schools?

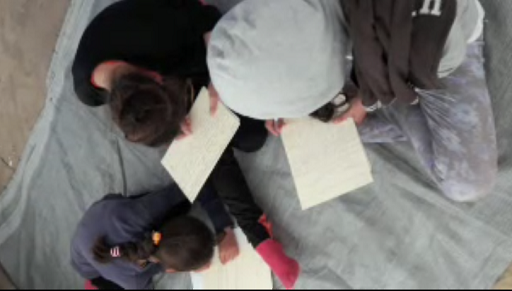

British headteacher Rory Fox runs a small charity called Edlumino, which raises funds to set up emergency schools in refugee camps around the world. In 2015 he set up a school in Faneromeni refugee camp in central Greece. First, watch the slideshow of images from Faneromeni camp and its primary school. Then listen to the interview with Rory Fox.

Transcript: Video 5: Faneromeni Refugee Camp, Greece

[SLIDE SHOW WITH NO SOUND UNTIL THE VERY LAST IMAGE, WHICH IS A SHORT VIDEO OF CHILDREN COUNTING]

CHILDREN

5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

Transcript: Audio 4: Interview with Rory Fox, Edlumino

INTERVIEWER

Can you describe the school? What it looked like?

RORY FOX

We went through several phases of school structure I suppose is a better word. We started out teaching literally in the open air sitting on mats. We’d use a couple of ground sheets just sitting on rubble. Quite often we’d have one of the children sitting at the edge on snake watch because the children got quite worried about the snakes that were there. So sometimes the children were just watching out. And it literally was sitting on rubble so it was quite uncomfortable sometimes. Also very, very exposed to the sun. During the summer it was quite unpleasant. Sometimes we had umbrellas. Sometimes we didn’t. Sometimes when it rained we’d get wet and we’d work as long as we could because for the children it was their only interaction some days. So we’d work as long as we could but it was very, very hit and miss.

So we progressed from working outside to taking the loan of a tent. But again it wasn’t ideal. It used to get flooded when the rain came. And then we progressed from that to a structure that was put up by essentially hammering pieces of scaffolding into the ground, stretching a cover, a groundsheet around the outside and then putting some corrugated plastic on the top. And that provided a structure that had three classrooms.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have any training or preparation for this kind of teaching?

RORY FOX

No. Just the standard training that we’ve had as school teachers. By and large that was sufficient because children are children wherever you find them. Some of the circumstances were a little more challenging and we did have days where we’d be teaching in tents that would be collapsing and struggling to remember how to tie a reef knot to keep the tent up or find a bit of a tree to replace a broken pole. But by and large the teaching side is, teaching is teaching.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re teaching in this context what are your goals? What are you trying to achieve and how is it different from a normal school?

RORY FOX

I think what we’re trying to achieve each time is to get the children to the age-related expectations. So if you’re working with a ten-year-old it’s about trying to get that ten-year-old in terms of reading, writing and maths to the levels that we would expect of a ten-year-old. Broadly international standards are broadly comparable, I mean there are some differences. But it’s trying to get that standard that we would recognise here in England and that qualifications like International Baccalaureate also recognise.

INTERVIEWER

How many children were there and what was the age range?

RORY FOX:

There was about 200 children in the camp and we would take about 100 daily. We were teaching mainly 5- to 11-year-olds but the older girls really found it difficult getting out of the camp. And some of that was about the fact they were on baby duty a lot of the time. Some of it was about the fact that the parents were very protective of the children. So the teenage girls would hang around the camp and as they heard what we were doing and had confidence in it they would then start presenting themselves for lessons. One day I walked in and found a group of 6-, 7-, 8-year-olds with a couple of 17-year-olds sitting there alongside them.

INTERVIEWER

Were there any surprises for you apart from the teenage girls?

RORY FOX

Yeah. I think every day had at least one surprise. Because sometimes the children would turn up with injuries and they’d be saying things like, you know, look my arm is bleeding. And you’d be saying, yeah, yeah, it’s bleeding. Right let’s stop the lesson. Let’s get some bandages out. And sometimes the children were hungry or they didn’t have clothing. Or sometimes there’d be a crisis in the camp. I remember one day we had a thunderstorm and the children thought ISIS were attacking again because they’d fled a village where they’d been attacked and the thunder sounded like gun fire. And we just had pandemonium, children running everywhere. We had to stop lessons for the rest of the day because they were just too traumatised by it.

INTERVIEWER

And the curriculum. Were you using the UNICEF curriculum? Can you tell us about that?

RORY FOX

We had a very, very simple curriculum actually. We essentially focused on English and maths. You might say why focus on English when the children mostly didn’t speak any English. But it was the one request that we consistently got from every family is to do English. They wanted English more than maths. They wanted English more than their own language. And I think that came as a little bit of a surprise to me about how valued English was. So we taught a lot of English.

And part of the reason for that as well is that in the camps English is the lingua franca of the international aid community. So in terms of what we taught the children with English we would often start with emergency phrases. So we would do parts of the body so that they could explain if they’re injured, you know, my arm hurts or my eye hurts. We would work through items of clothing and items of food so they could explain if they needed something. A bit of basic vocabulary again so they can explain if there’s a problem. And then the focus was on the English for maths because to teach maths you need vocabulary like equals and plus and takeaway. So we do that kind of vocabulary. And I think what we found is that trying to get the English and maths moving we often didn’t have time to get to the broader UNICEF curriculum, where there were the lessons on wellbeing and hygiene and health. Sometimes we did that sort of stuff but actually we would try and get other groups to do it because having professional teachers present it didn’t seem like the best use of the teachers when we could do the English and maths which the other groups couldn’t do but they could to the health and hygiene as well as us. So I think it was better to ask those groups to do that kind of stuff.

INTERVIEWER

Was the UNICEF curriculum helpful or useful?

RORY FOX

I think as a vision it was logical and coherent. But I think it’s a little bit like what you find in any normal school that you give teachers a curriculum and the first thing that they’re going to do is start adapting it and modifying it. Because every group of children is a little bit different. And even with something like that national curriculum I’d be surprised if any school in the UK ever teaches just the national curriculum. You know, the whole national curriculum and nothing but the national curriculum. Normally there’s a little bit of modification.

INTERVIEWER

What do the children themselves want to learn?

RORY FOX

English. Very much. English, English, English. And maths actually. One of the things that really surprised me is that when we started out teaching maths initially we would get the response ‘no maths, no maths’ just English. But after a little bit of time we actually had girls turning up saying, maths, please maths. Because of the girls had never learnt any maths at all. And I remember a group of 15-year-old girls who had never, ever done any maths in their life. And my first lesson with them was trying to convey the concept of taking away. And I wasn’t entirely successful because some of the girls grasped it straightaway, you know, hold your fingers up, here’s five fingers. And look I’m taking these two away, how many fingers are left. And actually the girls just struggled with the concepts. They couldn’t conceptualise taking away. I’ve never encountered anything quite like it. And it may be that some of the children had special needs. I think definitely some of them had special needs.

But I think also what it showed me is that children learn things at particular points in their life. And learning those fundamental concepts like adding and taking away. If you haven’t got it early sometimes it takes a lot of trouble to acquire it later. But I think the teenage girls in particular they came to really enjoy the maths. And they would come and ask for it. And there was one girl that I worked with that had never done any before and in about a week she did as much as we would normally do in a month, a phenomenally able young lady.

INTERVIEWER

Are there things that you know now, having done more of it, that you didn’t know at the time?

RORY FOX

Yes. I think one of the things that we came to realise is that teaching reading from a phonic series doesn’t work in an ESOL context. Because the phonic series, the kind of words that are used for phonics are not the high frequency words that you would be introduced to when you’re first learning the English language.

You’d often get words included because of their sounds. Like you’d get kangaroo, because you get a nice roo sound. Which is great if you’re a natural speaker of the language then you approach school with quite a large vocabulary. But if you are a Kurdish or Arab child who has had a little bit of English but not a lot of English, or you’d been out of school for three or four years, as many of these children had, then you’re approaching the lessons with very, very little English. And the English that the children need is really the high frequency words.

So the kind of language that you would use to start reading and writing in English is very, very different than the words that you would learn, like kangaroo, you’re not going to use that generally every day.

RORY FOX

I think generally the resources were entirely inappropriate because they generally consisted of what we could scavenge from other sources. So we would have books that were literally the remains at the back of cupboards from schools in either England, France or Germany. At one point I remember having a set of books in front of me where I had a set of atlases. I had a French one, a German one and an English one. And, you know, poor old teachers are having to translate, Allemagne, which country is that? That’s Germany, that’s the French word for Germany, and here I’ve got the German word for Germany. And actually it’s quite a strain.

INTERVIEWER

When you look back on that experience what do you think the lessons are that you have learnt and how has it changed you as a teacher or as a person?What we found as well is it was very, very difficult to report crimes. You’d have children potentially alleging quite serious matters. And you’d go to the police and the police first question was ‘Is the child an EU national?’ And we’d say well no obviously. And then their response was not interested. So you’d have children trying to report rape, attempted murder, kidnapping and the police are not interested. And as a teacher I really didn’t know what to do about that. And I’m still not quite sure what I should have done. Because in the UK if you’ve got a child protection issue or a social services issue you’ve got a phone number, you ring someone and someone can do something. At Fanomeri we had a very, very dubious situation of a local resident that would wander in to the camp and take little boys off on his own. And go missing for a long time with these children and then bring them back with loads of presents. Now to my mind that rings so many alarm bells but I couldn’t get anyone to take that seriously. In fact we only finally got it resolved because I found a local Greek lawyer. And then the lawyer was able to take it up with the police and threaten all sorts of legal stuff if something wasn’t done about it.

INTERVIEWER

Something else we haven’t really touched on is the trauma that the children had experienced. How was that felt in the classroom?

RORY FOX

I think there’s two very different issues that trauma gave rise to. On the one hand because some of the children had come from very, very difficult backgrounds there was a tendency amongst some of the aid workers to lower their expectations. So I was told several times that I shouldn’t be teaching children to write, that they should be colouring in, because they’re too traumatised. And there was one crazy day where we had a group of teenagers actually doing algebra and getting it all correct. And someone wandered in and said they shouldn’t be doing that, they should be colouring in. And actually here were children making up for years of missed education. Some of those children have not been in school for three years. They were catching up. They were catching up quickly and yet there were aid workers potentially, for very good reasons, potentially wanting to deny them that catch up because of their trauma. Now having said that there were days when the children were very traumatised. You know, the day we had thunder and they thought they were being attacked, we just had to stop lessons that day. Other days children would come in and sometimes they’d be weeping. What could we do about that? Well very little because we had no one to refer children to. There were no kind of psychologists going to come in and do something. So we largely had to work through the trauma issues. When the children were traumatised we’d sort of talk to them a little bit in the way that any school pastoral system would work. We would do what we could. Sometimes that would help the children, sometimes we had to let it just play out a little bit because we could only do what we could do.

INTERVIEWER

You talked about trauma. What about the general mental health and wellbeing of the children?

RORY FOXI think some of the children were extremely unwell, that had quite considerable mental health issues that weren’t being picked up. We encountered, you know I’m thinking now of one young lady that was so depressed she wouldn’t come out of her tent. And the other children came to us and said she’s got the sadness sickness, that she wouldn’t come out. And over a period of about six weeks we enticed her out of the tent. We enticed her to the door of our tent, but she wouldn’t come in. Then she came in but she wouldn’t sit down. Then she sat down but she wouldn’t get involved. And finally after six weeks she started getting involved in lessons.

And actually the lessons normalised her experiences. And actually started to help her to recover. And I think one of the things that people don’t reflect enough on in schools in camps is that they’re often described as activities. So school is an activity for the children. And it’s often equated with things like they’re doing jigsaws or playing football, you know, they’re all activities. But I think what is sometimes forgotten is that for children school is their normal life. Providing school in a camp is normalising the children’s experiences. And for children that have got mental health issues and issues arising because of the lack of normality, then providing a school is an incredibly important part of helping with them with their mental health issues.

Jane Williams-Siegfredsen trained as a teacher in England and went on to become a teacher educator. In 1990 she went on a study trip to Denmark, where she visited a ‘nature kindergarten’. Since then, Jane has become a leading figure in the Forest School movement. First, watch the slide show of a variety of forest schools in Denmark. Then listen to the interview with Jane Williams-Siegfredsen.

Transcript: Audio 5: Interview with: Jane Williams-Siegfredsen, Forest School Pedagogue

INTERVIEWER

Jane, my first question is how you got in to this type of teaching and what drew you to the forest school environment as a teacher?

JANE

I think first of all it was when I trained to be a teacher and my main subject was environmental science. So I used the outdoor environment as much as possible when I first started teaching an in inner city school in Liverpool, which was quite difficult because there really wasn’t any green area around, so I had to be imaginative how I could use environmental education.

I then moved on and did other things, worked in other schools. And then I was working at a college in the south west of England. And we’d heard a lot about the early years practice in Denmark and how good it was. So we arranged a study trip for some students and we came over, it must be about 25 years ago now. The first kindergarten I went to with some students was a nature kindergarten. And I was completely bowled over. I just saw these children being so competent and confident, and the pedagogues trusting them so much in what they did.

I was also terrified, The first thing I saw was a child really high up in a tree. And the pedagogues, the educators here weren’t really concerned, didn’t seem to be taking any notice of this child who was high up in the tree. And I was screaming and shouting underneath the tree to the educators, the pedagogues, to make them aware that this child, it looked very dangerous to me. And with their typical Danish humour they said, well they don’t usually fall out of the trees. So, yes, it was a life changing experience I would say.

INTERVIEWER

What is it about taking risks like that? It’s very different to what we call health and safety practices in the UK.

JANE

Very much so. The difference I see here is the word trust. There’s a great deal of trust in the Danish society, you’re trusted to do that job, and that trust seems to filter throughout society here. So the parents trust the pedagogues and the pedagogues trust the children. The children trust the pedagogues. It’s part of that mind set, this trust that there is in society here, and the children learn how to take risks and they learn how to assess risks. What I saw in the UK before moving here was really that we disabled children because we didn’t trust then. It was a case of get down, you’ll fall, don’t do that you’ll cut yourself. Always pre-proposing that they’re incompetent. Whereas here I feel that the children are treated as competent. And those competencies are developed by the pedagogues in the kindergartens.

INTERVIEWER

So, in your view, what are the goals of this type of early years education in Denmark in terms of outcomes of that kind of education?

JANE

Those who work in nature kindergartens are very committed though to the children being outside every day all year round. Not necessarily all day, but a part, a large part of every day all year round. And developing those competencies and skills and self-awareness that actually being outdoor gives more than being indoors.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think the outdoors gives that kind of confidence more than being in the indoors classroom?

JANE

I think one thing I would stress is that there’s a lot of physical work outside, a lot of physical development, a lot of social and emotion development outside where children are being outdoors and walking over uneven terrain and swinging in branches of trees. And this develops their sensory development a lot. And from recent research it looks like that we really need that all-round sensory development if we’re going to be able to learn at school, to read, write, do mathematics, all those sorts of things, it’s really important that we have that sensory development.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk a bit about how the pedagogue would plan the forest school session or the day in the forest school?

JANE

When they go outside it could be something that’s planned, so rather adult-led in what they’re doing, where the pedagogues have decided, for example, in a kindergarten that’s right by the fjord they might have planned, right this is the time we’re going to get all the waders and safety vests on. And groups of children are going to go into the water to maybe look for shrimps or whatever there is in the water. And that would be a planned thing.

More often than not, it’s child led. They go outside and the children find their own things. They want to swing. They want to slide. They want to run around. They want to dig. And then maybe at lunchtime, it may be a time where they’ve lit the fire outside and they’re cooking outside.

Children are naturally inquisitive and want to find out how things work and what things are and there’s a wealth of things outdoors for children who are inquisitive. Some children like different things. Some children maybe like, not climbing, but they like digging or they like transporting, they like moving things from one area to another. So individual children’s needs can be taken into account in the outdoors as well.

INTERVIEWER

That’s really interesting, thinking about the early years understanding of schemas. How is that observed in the forest school? You talked about climbing, about digging.

JANE

Yes. I mean you see all the schemas in the outdoor environment because everything is there ready for children to develop those schemas and move on and work things out. There’s so much chance for transporting things, for going round things and under things and climbing things. There’s just every possibility I think outdoors.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk about the difference between a teacher and a pedagogue, because you’ve used that word a few times, and the meaning of the word pedagogue?

JANE

In Denmark there are teachers and they teach in the mainstream schools, which is from six years to 16 years. And the pedagogues work around everything else I would say. They work in early years. They work also in the school supporting the teachers with the younger children. They work in special needs. They work with out-of-school care. They work with teenagers. They work with adults. They work with families. And they also work with the elderly.

Interviewer:

And what kind of knowledge and skills do pedagogues need that is different to what a teacher does?

JANE

I think the main role that a pedagogue has is supporting the child holistically. They’re not just looking at their cognitive development, for example, or what they’re learning as such. They really firstly want to create a safe environment where the children can thrive and develop in creatively stimulating surroundings.

INTERVIEWER

If you’re a forest school or an outdoor kindergarten pedagogue, isn’t it stressful to see children taking risks? You talked about your own shock at seeing a child going up a tree. I would imagine that they have to be very calm about seeing children taking risks.

JANE

The pedagogue training is now three and a half year Bachelor level training. And a lot of the training first of all is about the training pedagogues own self-awareness. So they go away, for example, kayaking or abseiling. They learn about their own risk taking and their own views about risk.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, if you become aware of your own sense of risk then you’re more able to assess a child’s risk-taking behaviour. With children taking these risks in an outdoor environment, in your experience has anything ever really bad happened to a child, anything physically traumatic to a child in these environments?

JANE

Well again talking to the lead pedagogue at the kindergarten that’s right by the fjord was asked what’s the worst accident that’s happened. And he said, well in his 17 years of working there he’s only ever had to take a child to hospital once. And that was because a parent backed their car up and ran over a child’s foot.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think the outdoor environment, the outdoor classroom, is more gender neutral than the indoor school environment?

JANE

Yes, definitely, definitely.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that, do you think?

JANE

I think because the outdoor environment is natural. There are trees. There are pieces of wood. There’s soil. There’s sand. There’s hammocks. There’s all those sorts of things. There’s nothing saying this is boy, this is girl. It’s there for everyone and the children use it in their own way. I think outdoors, it’s neutral.

I think the outdoor environment is so rich in what’s out there for the children to use and they use their imaginations rather than picking up something that’s been designed to be used in a certain way. Outside, the tree trunk could be a tree trunk or it could be an aeroplane or it could be a boat in the middle of the ocean. It can be anything that the child imagines it to be.

INTERVIEWER

So, if one of our students wants to become a forest school pedagogue, you talked about kind of assessing their own sense of risk. But how else would a student prepare to enter this kind of professional area?

JANE

Well obviously you have to like the outdoors, whatever the weather. You have to be playful and creative and imaginative. You have to have many competencies. You have to have knowledge about plants and trees and creepy crawlies and birds. But you don’t have to have a PhD in that. There are many ways that we can find things out. Quite often we find things in the forest with the children and we don’t know what they are. So we have to maybe get our iPad out, or we go back to the kindergarten and get the reference books out. Children love finding out. And the pedagogues help them. They don’t tell them what things are. We discover things together. I would say to practitioners, I’d say take the risk and try it, go outside. Take small steps. Don’t try and become a Danish Nature Kindergarten overnight, it’s not possible. You have to bear in mind the culture and environment that you’re working in. So what’s OK for Denmark maybe isn’t OK in Australia or the UK or America. So you have to think about your own culture and what’s accepted and what’s not accepted.

You also have to work with parents because the parents need to understand that you are also taking their child very seriously and their welfare seriously. You need to have the parents on your side so that they know that you are going to care for them, when they’re outside they’re not going to fall out of a tree or cut their finger off or, yes, be bitten by a snake or whatever it might be in your country. I have many people come from Australia or China or America, the UK, wherever, and when we talk at the end of each day’s session of being out in a kindergarten, I ask them, so what could you get from, what have you got from today? Is there anything there you could take back and develop in your practice? And it’s generally the things of ... like the trust, like the stepping back more often than you step in. So you wait and see if children can do something by themselves before you start doing it for them. The idea of looking at a child holistically and individually and seeing them as unique and competent in their own right.

Add your reflections to the box below.

Discussion

The two types of school described in these interviews could not be more different. One is extremely challenging and chaotic, where children are traumatised and teachers work with few – and sometimes inappropriate – resources. The other is highly resourced and child-led, where teachers have considerable freedom to plan and support children’s exploratory play and learning. The activities in the Danish forest school are familiar to all the participants and are based on the country’s cultural and educational heritage. The activities in the refugee camp school in Greece may be very unfamiliar to the children, and in a language they do not use.

But notice how, in both schools, the teachers are agile and adaptive to the needs of the children. And in both schools there is the same dedication of teachers to the children in their care, and the commitment of teachers to creating educational experiences that sustain children to grow and develop in a positive direction. In both schools teachers strive to provide quality, learner-centered education.