2.1 Choose your theory

These next readings are an opportunity to spend some more time thinking about a leadership theory that interests you.

Activity 3 Choose your theory

Read these Abstracts and then choose at least one section of a paper to read in detail. As you are reading make notes about:

- What are the characteristics of the theory that are in evidence?

- What are the positive aspects of these experiences as they are presented?

- What kinds of challenges emerge for the teachers and the leaders?

- How does the experience relate to your own experiences of leading and being led?

- Can you see benefits from this way of leading that speak to your understanding of inclusive education and the challenges it faces?

- Why do you think that Óskarsdóttir et al (2020) felt it was necessary to use more than one theory in developing their model of inclusive leadership?

When you have finished reading you may want to have a discussion with friends or colleagues about leadership styles and their experiences of them.

Read Gómez-Hurtado, I., González-Falcón, I., Coronel-Llamas, J. M. and García-Rodríguez, M. D. P. (2020) ‘Distributing leadership or distributing tasks? The practice of distributed leadership by management and its limitations in two Spanish Secondary Schools’, Education Sciences, 10(5), p. 122. Read from Results (p. 5) to the end of the paper (p. 12). Abstract: The need to explore new forms of leadership in schools, among other available alternatives, leads to the reflection upon the way in which--specifically from the principal's office--it is developed, implemented and distributed. This paper presents two case studies in Spanish secondary schools in which the practices are analyzed and the limitations recognized in the exercise of distributed leadership by their principals. This study used interviews and shadowing of the principals, recording the observations of meetings and interviews with other influential agents from each school. Despite the particular differences in each case and a greater role of social interaction processes, the outcomes reflect the persistent focus on the individual action of the principals and the pre-eminence of formal and bureaucratic components in the development of distributed leadership. This situation prevents progress beyond the mere distribution of management tasks and hinders the possibilities of consolidating other forms of leadership expression that involve more agents and groups. |

Chabalala, G. and Naidoo, P., (2021) ‘Teachers’ and middle managers’ experiences of principals’ instructional leadership towards improving curriculum delivery in schools’, South African Journal of Childhood Education, 11(1), pp. 1–10. http://www.scielo.org.za/ scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2223-76822021000100017 Read from Findings (p. 5) to the end of the paper (p. 10). Background: This study was designed to explore teachers’ and middle managers’ experiences regarding their principals’ instructional leadership practices aimed at improving curriculum delivery in schools. Literature on instructional leadership indicates how failing schools can be turned around to become successful if principals consider instructional leadership to be their primary role within schools. The authors, therefore, argue that it is the responsibility of principals to ensure that learners’ results are improved through intervention and support provided by the principals to capacitate teachers and middle managers in delivering the curriculum effectively. Globally, literature promotes the significance of the continued professional development of teachers, and many scholars allude to the pivotal role principals or school heads play in teachers’ skills advancement. Aim: The aim of this article was to identify principals’ instructional practices that improve curriculum delivery in schools, which are examined through the experiences of teachers and middle managers. Setting: The study was conducted in two schools in the Gauteng province of South Africa. Method: The researchers employed a qualitative approach, utilising three domains of instructional leadership as its framework, and these are defining the school mission statement, managing the instructional programme and promoting a positive school learning climate. Four teachers and four middle managers were purposefully selected at two schools for data collection conducted through semi-structured individual interviews, which were analysed using thematic content analysis. Results: Three themes emerged, namely, understanding good instructional leadership practices, teacher development as an instructional practice and instructional resource provisioning. Conclusion: The study highlights the importance of teachers and middle managers in understanding that principals are merely not school managers or administrators, but rather instructional leaders whose primary role is to direct teaching and learning processes in schools. Principals need to create time within their constricted schedules to become instructional leaders, which is their main purpose in schools. If the roles and responsibilities of middle managers are not explicit, their ability to simultaneously perform the dual task of being teachers and middle managers will be compromised. |

Asare, K. B., (2016) ‘Are basic school head teachers transformational leaders? Views of teachers’, African Journal of Teacher Education, 5(1). Read from Results and Findings (p. 7) to the start of the Discussion (p. 15). Abstract: Transformational leadership practice is associated with improved school functioning and quality education delivery through teacher commitment and willingness to exceed targets or educational benchmarks (Balyer, 2012; Nedelcu, 2013). The establishment of the Leadership for Learning (LFL) program in Ghana in 2009 aimed at improving the effectiveness of basic school head teachers to better lead schools to promote student learning. In this study, the perceptions of basic school teachers as to the transformational leadership conduct of head teachers who had received training under the LFL model were collected and reviewed. The purpose of this qualitative inquiry was to determine from teachers’ perceptions how the conduct of head teachers related to transformational leadership. From the study results, the findings indicated that while teachers largely perceived their head teachers as transformational leaders, more than the influence of head teachers is required to motivate teachers to give of themselves to improve education outcomes. Recommendations and implications of the study for practice and research were considered. |

Discussion

When reading papers such as these, it seems that some people are seeking to solve complex educational leadership issues by using a single theoretical lens. But as Kwan (2020) notes, there is an underlying inadequacy when we reduce organisational leadership into a singular, conceptual framework. For example, Leo and Barton (2006) point to a couple of inherent challenges for distributive leadership. Firstly, the decision-making authority about what is distributed and to whom is almost certainly going to reside with an executive role, and secondly, many staff members do not wish to undertake additional responsibilities, even if they wish to work in inclusive ways.

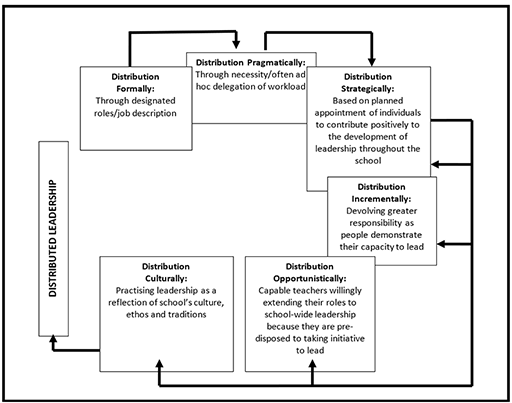

It is important to recognise too that there are many different models associated with these theories and useful variations which can help with reflecting upon our practices. For example, MacBeath produced a taxonomy of distribution, to explore the different options available to leaders as they work with the power and authority (see Figure 5). The model includes six typologies of distributed leadership: Formal, Pragmatic, Strategic, Incremental, Opportunities and Cultural. The typologies do not represent single styles since they are evidenced in various ways according to the context and the nature of the people involved. As you work your way clockwise around the figure below, you will see that it starts by describing more formalised ways of distributing leadership and then less tangible ones. It is possible to see here, how a headteacher might find ways to distribute leadership without making it feel like taking on ‘additional responsibilities’.

It is also worth noting that there are a wide variety of other models associated with leadership. Precey & Mazurkiewicz (2013), for example, mention Transformative leadership. This is an approach that is founded on critique and aspiration, underpinned by values of democracy, social justice and equity. Leaders who adopt this style are interested in how systems and processes de-construct and reconstruct institutions, social norms and cultural knowledge; they seek to transform individuals and organisations; and they wish to encourage activism and moral courage, recognising the challenges and tensions in the lives we live.