A traditional PhD, a Doctor of Philosophy, usually studied full-time, prepares candidates for a career in Higher Education.

A Professional Doctorate is usually studied part-time by mid- to late-career professionals. While it may lead to a career in Higher Education, it aims to improve and develop professional practice.

We offer two Professional Doctorates:

- A Doctorate in Education, the EdD and

- a Doctorate in Health and Social Care, the DHSC.

Achieving a doctorate, whether a PhD, EdD or DHSC confers the title Dr.

Why write a Research Proposal?

To be accepted onto a PhD / Professional Doctorate (PD) programme in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies (WELS) at The Open University, you are required to submit a research proposal. Your proposal will outline the research project you would like to pursue if you’re offered a place.

When reviewing your proposal, there are three broad considerations that those responsible for admission onto the programme will bear in mind:

1. Is this PhD / PD research proposal worthwhile?

2. Is this PhD / PD candidate capable of completing a doctorate at this university?

3. Is this PhD / PD research proposal feasible?

Writing activity: in your notebook, outline your response to each of the questions below based on how you would persuade someone with responsibility for admission onto a doctoral programme to offer you a place:

- What is your proposed research about & why is it worthy of three or more years of your time to study?

- What skills, knowledge and experience do you bring to this research – If you are considering a PhD, evidence of your suitability will be located in your academic record for the Prof Doc your academic record will need to be complemented by professional experience.

- Can you map out the different stages of your project, and how you will complete it studying i) full-time for three years ii) part-time for four years.

The first sections

of the proposal - the introduction, the research question and the context are

aimed at addressing considerations one and two.

Your Introduction

Your Introduction will provide a clear and succinct summary of your proposal. It will include a title, research aims and research question(s), all of which allows your reader to understand immediately what the research is about and what it is intended to accomplish. We recommend that you have one main research question with two or three sub research questions. Sub research questions are usually implied by, or embedded within, your main research question.

Please introduce your research proposal by completing

the following sentences in your notebook:

I am interested in the subject of ………………. because ………………

The issue that I see as needing investigation is ………………. because ……………….

Therefore, my proposed research will answer or explore [add one main research question and two sub research questions] …...

I am particularly well suited to researching this issue because ……………….

So in this proposal I will ……………….

Completing these prompts may feel challenging at this stage and you are encouraged to return to these notes as you work through this page.

Research questions are central to your study. While we are used to asking and answering questions on a daily basis, the research question is quite specific. As well as identifying an issue about which your enthusiasm will last for anything from 3 – 8 years, you also need a question that offers the right scope, is clear and allows for a meaningful answer.

Research questions matter. They are like the compass you use to find your way through a complicated terrain towards a specific destination.

A good research

proposal centres around a good research question. Your question will determine

all other aspects of your research – from the literature you engage with, the

methodology you adopt and ultimately, the contribution your research makes to the

existing understanding of a subject. How you ask your question, or the kinds of

question you ask, matters because there is a direct connection between question

and method.

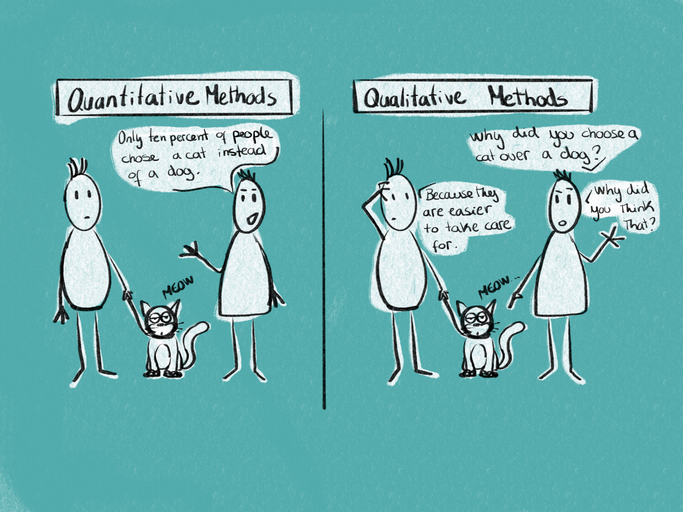

You may be inclined to think in simplistic terms about methods as either quantitative or qualitative. We will discuss methodology in more detail in section three. At this point, it is more helpful to think of your methods in terms of the kinds of data you aim to generate. Mostly, this falls into two broad categories, qualitative and quantitative (sometimes these can be mixed). Many academics question this distinction and suggest the methodology categories are better understood as unstructured or structured.

For example, let’s imagine you are asking a group of people about their sugary snack preferences.

You may choose to interview people and transcribe what they say are their motivations, feelings and experiences about a particular sugary snack choice. You are most likely to do this with a small group of people as it is time consuming to analyse interview data.

Alternatively, you may choose to question a number of people at some distance to yourself via a questionnaire, asking higher level questions about the choices they make and why.

Context

Once you have a question that you are comfortable with, the rest of your proposal is devoted to explaining, exploring and elaborating your research question. It is probable that your question will change through the course of your study.

At this early stage it sets a broad direction for what to do next: but you are not bound to it if your understanding of your subject develops, your question may need to change to reflect that deeper understanding. This is one of the few sections where there is a significant difference between what is asked from PhD candidates in contrast to what is asked from those intending to study a PD. There are three broad contexts for your research proposal.

If you are considering a PD, the first context for your proposal is professional:

This context is of particular interest to anyone intending to apply for the professional doctorate. It is, however, also relevant if you are applying for a PhD with a subject focus on education, health, social care, languages and linguistics and related fields of study.

You need to ensure your reader has a full understanding of your professional context and how your research question emerges from that context. This might involve exploring the specific institution within which your professionalism is grounded – a school or a care home. It might also involve thinking beyond your institution, drawing in discussion of national policy, international trends, or professional commitments. There may be several different contexts that shape your research proposal. These must be fully explored and explained.

Postgraduate researcher talks about research questions, context and why it mattered

Student

Supervisor

The second context for your proposal is you and your life:

Your research proposal must be based on a subject about which you are enthused and have some degree of knowledge. This enthusiasm is best conveyed by introducing your motivations for wanting to undertake the research. Here you can explore questions such as – what particular problem, dilemma, concern or conundrum your proposal will explore – from a personal perspective. Why does this excite you? Why would this matter to anyone other than you, or anyone who is outside of your specific institution i.e. your school, your care home.

It may be helpful here to introduce your positionality. That is, let your reader know where you stand in relation to your proposed study. You are invited to offer a discussion of how you are situated in relation to the study being undertaken and how your situation influences your approach to the study.

The third context for your doctoral proposal is the literature:

All research is grounded in the literature surrounding your subject. A legitimate research question emerges from an identified contribution your work has the potential to make to the extant knowledge on your chosen subject. We usually refer to this as finding a gap in the literature. This context is explored in more detail in the second article.

You can search for material that will help with your literature review and your research methodology using The Open University’s Open Access Research repository and other open access literature.

Before moving to the next article ‘Defining your Research Methodology’, you might like to explore more about postgraduate study with these links:

- Professional Doctorate Hub

- What is a Professional Doctorate?

- Are you ready to study for a Professional Doctorate?

- The impact of a Professional Doctorate

- Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

- Succeeding in postgraduate study - OpenLearn - Open University

- Are you ready for postgraduate study? - OpenLearn - Open University

- Postgraduate fees and funding | Open University

- Engaging with postgraduate research: education, childhood & youth - OpenLearn - Open University

We want you to do more than just read this series of articles. Our purpose is to help you draft a research proposal. With this in mind, please have a pen and paper (or your laptop and a notebook) close by and pause to read and take notes, or engage with the activities we suggest. You will not have authored your research proposal at the end of these articles, but you will have detailed notes and ideas to help you begin your first draft.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews