3 The life cycle model of stress

As you have seen, the overall picture emerging from studies of how stress affects the brain is that chronic or repeated exposure to stress can affect the structure of several areas of the brain via the action of glucocorticoids released during activation of the HPA axis.

Recently, researchers have begun to ask whether this is too simplistic and whether the effects of stressful or traumatic experiences depend on the age at which they occur.

Developmental biologists have long known that environmental (including social) factors can have particularly long-lasting effects if experienced early in life or at other ‘vulnerability periods’. Early effects, which can set an individual on a particular developmental path for life, have been described as ‘programming effects’.

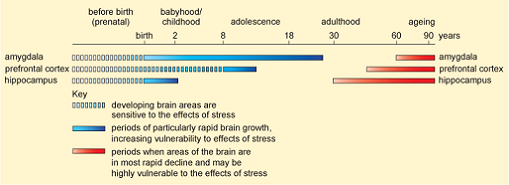

The life-cycle model of stress proposes that stressful experiences will have a high impact on brain structures that are growing most rapidly at the time of the stress exposure (in young individuals), or that are undergoing age-related decline (in adult and old individuals).

As Figure 8 shows, in humans, different brain structures develop or reach maturity at different ages. This is certainly true of the three brain regions we have already identified as having an important role in the control of the HPA axis, and which are therefore of particular interest – the hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

Which areas of the human brain are developing or growing rapidly in the period:

- a.prenatally

- b.from birth to 2 years

- c.between 11 and 12 years?

- a.The hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and amygdala.

- b.The hippocampus and amygdala.

- c.The prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

Effects on the hippocampus, which in humans is actively growing prenatally and after birth, have been of particular interest because of its importance in the control of the HPA axis.

Studies have shown that if stress occurs when participants or subjects are young, damage to the hippocampus and the subsequent effects on behaviour are indeed long-lasting and difficult to reverse. But if stress occurs in adulthood, the effects, even of chronic stress, are reversed after only a few weeks of non-stress.

Age-related effects were found by McCauley et al. (1997) in a study of more than 1900 women: they found that in childhood, but not adulthood, sexual or physical abuse was a strong predictor of increases in depression and anxiety.

How might the link between child abuse and depression arise? In Activity 6 you saw that the undamaged hippocampus has an important role in controlling the HPA axis and calming the stress response. Early damage to the hippocampus, as a result of severe or prolonged stressful experiences such as childhood abuse, has potentially long-lasting effects on control of the stress response.

What is a human example from earlier in this section where adverse early experience was linked to an over-active stress response?

Women who had been abused as children had a stress response that was over-active during the Trier social stress test, compared to women who had not been abused in childhood.

A poorly functioning hippocampus may thus be a ‘vulnerability factor’ or ‘diathesis’, for depression when further stress is experienced. Such stress would trigger a badly controlled stress response which could further damage the hippocampus and other brain structures and could predispose to depression. Repeated episodes could lead to significant changes in the volume of the hippocampus and other brain areas.

Can you be sure that early life stress is the only factor contributing to small hippocampus size and dysfunction?

No, it is crucial to recognise that you cannot. It is possible that other influences such as genetic factors also influence hippocampus size and dysfunction.

The life-cycle approach thus promises to add a valuable perspective to research on the aetiology of affective and anxiety disorders, as a very brief consideration of another example, to conclude this section, will confirm.

Hall (1998) suggested that if different parts of the brain are vulnerable to stressful, adverse circumstances at different ages, different mental disorders might be associated with stressful experiences at different ages. Thus stress at the time of rapid hippocampal development might lead to different emotional disorders than stress at times of rapid prefrontal cortex development.

Some recent human data seem to offer support for this hypothesis: women who experienced trauma before the age of 12 years had increased risk for major depression, whereas women who experienced trauma between 12 and 18 years of age more frequently developed PTSD (Maercker et al, 2004).

More longitudinal studies of individuals are clearly needed to fully explore the potential of the life-cycle approach.