Brighton Pavilion

1 The Royal Pavilion

In this unit we shall be studying a quintessentially Romantic piece of architecture, the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, designed and redesigned over the course of some 30 years to the specifications of the Prince of Wales, afterwards Prince Regent and eventually King George IV (1762–1830; reigned 1820–30).

The Pavilion as we now know it in its final state was the result of a collaboration between the architect Sir John Nash (1752–1835), the firm of Crace (specialists in interior decoration) and their patron the Prince Regent. It makes a suggestive companion piece to the house of Sir John Soane.

Although both buildings are markedly personal in cast, Soane's house can be regarded as a Romantic ‘take’ on Enlightenment classicism, while the Pavilion could be called a Regency ‘take’ on the Romantic (what I mean by this distinction will become clearer as we progress). Whereas Soane's house celebrates the architect as sole creator, the Pavilion is much more typically the product of a collaboration between architect and client.

While Soane was and is the architect's architect, an intellectual and an academic, distinguished, original and serious, Nash was the darling of fashionable aristocratic society, careless, humorous and audacious in style, and was and is identified with the commercial and the opportunistic. Where Soane is essentially a purist, refining and romanticizing Neoclassicism, Nash is associated with eclecticism, which by contrast privileges asymmetry and recklessly mixes forms, motifs and details from different historical periods and styles.

The Pavilion itself has been called silly, charming, witty, light-hearted, extravagant, gloriously eccentric, decadent, childish, painfully vulgar, socially irresponsible, a piece of outrageous folly and a stylistic phantasmagoria. Whatever you decide about it, it has always been, beyond all dispute, an astonishing flight of the Romantic fancy, comparable in its impulse to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's famous poem ‘Kubla Khan’ (drafted 1798, published 1816, available to read in its entirety beneath the extract below. The poem begins:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Click on 'View document' to see Coleridge's poem 'Kubla Kahn' in its entirety.

Coleridge's poem did not in itself influence the building of the Pavilion, but both ‘Kubla Khan’ and the Pavilion do recognizably grow out of a common stock of Romantic ideas and feelings about the Orient. Here we shall be trying to come to some understanding of how, why and to what effect the prince's ‘pleasure-dome’ translated some of the modes and ideas of Romanticism into the language of architecture.

As we do so, we'll be thinking about the Pavilion as what we might call a ‘cultural formation’. By this I mean that considering the apparent eccentricity of this building can give us an insight into many aspects of Regency culture, and, conversely, that an enhanced knowledge of Regency culture can help us to decode the meanings of the building for its own time.

The Pavilion can be seen as the physical realization of the coming together of many aspects of Regency society: systems of patronage of the arts; ideas of health, leisure and pleasure; notions of technological progress, which drove the Industrial Revolution and were in turn reinforced by it; concepts of public and private and the proper relations between them; ideas of royal authority in the post-Napoleonic era of restoration of hereditary monarchies across Europe; the fashion for Oriental scholarship and the ‘Oriental tale’; and powerfully interconnected ideas of trade, empire and the East. By the end of the unit, therefore, you will, I hope, have developed a sense of some of the (sometimes contradictory) values dramatized by Romantic exoticism.

Before we can talk about the meanings of the Pavilion in its own time, however, you will need to familiarize yourself with the building. On the video clips (below), The Royal Pavilion, Brighton, you will find a virtual tour of the Pavilion, inside and out. The video is structured as though you were a visitor to the Pavilion in the early 1820s. You will trace the route through the rooms that you would have followed if you were arriving as a guest at one of the prince's famous evening receptions, consisting of dinner followed by music. You will hear on the sound-track the music that the prince loved, together with some of the comments of his guests, and extracts from contemporary descriptions of the Pavilion's interior from a newspaper and a guidebook.

Exercise 1

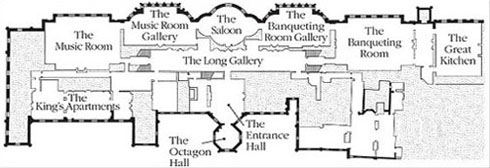

Read the accompanying AV Notes (below) and then watch all three video clips carefully once through. Concentrate principally on the look of the exterior and of the interiors. Then I suggest you watch the videos again, following your route on the modern ground-floor plan provided below (Figure 1), and looking carefully at the contemporary watercolours of exteriors and interiors provided below (Plates 1–11).

Once you have done this, compile a list of adjectives that occur to you to describe your experience of the building, both exterior and interior. You might also like to add to your list some phrases describing those effects in which this building is conspicuously not interested.

Click on 'View document' to see plates 1-11, watercolours depicting the interior and exterior of the pavilion.

Click on 'View document' to read the AV notes for the video below.

Click below to view clip 1 of the video.

Click below to view clip 2 of the video.

Click below to view clip 3 of the video.

Discussion

I don't expect that our lists will match exactly – but we might agree roughly on some of the effects that the building produces on us. What I've noted down is that the exterior strikes me as definitely ‘Indian’ – in fact, vaguely reminiscent of the Taj Mahal. The Entrance Hall, the Long Gallery and the Saloon are clearly ‘Chinese’, and so are the Banqueting Room and Music Room, although they are Chinese (with a dash of ‘Indian’?) in a rather different and much more grandiose mode. (Don't worry if you found it hard to put your finger on the exact difference in style; we'll be unpicking these Indian and Chinese effects in more detail a little later.)

After that, I have a list of descriptive terms that runs something like this: conspicuously expensive; sumptuously detailed to the suffocating edge of over-kill; self-advertising; highly personal, fantastic and esoterically refined; spectacular, theatrical and faintly reminiscent of some of the pleasures of Disneyland's evocations of foreign parts; sensual to the point of overwhelming the senses; and, related to this, disorientating (all those mirrors and all that trompe l'oeil); an escapist pocket palace.

As for what this building is not trying to do or be – it is spectacularly not invested in neoclassical politeness, nor in antiquities or other sorts of collectables. The Pavilion is profoundly uninterested in the past, the nation or conventional domesticity, in respectability, or in social responsibility, or in work of any sort. Related to this last point, it is conspicuously not the centrepiece of landed wealth – it is not standing in a place of eminence, embedded within its own estate and associated farms which would be visibly providing the income for the upkeep of the house. Carrying this thought a little further suggests forcibly that the wealth this palace is designed to display is a wealth of taste and imagination. Above all, this building is surprising.

Actually, I'd go further than this – I think this building is astonishing, and its sheer improbability generates in me a curiosity about the circumstances that could conceivably have made it possible.

Exercise 2

Now I want you to try to formulate a set of questions that the Pavilion might prompt about the culture that produced it. To this set of questions, I should like you to add a list of the sorts of information you would need to collect about that culture so as to be able to answer them. (If you are feeling especially imaginative and adventurous, you might like to write yet another list of suggestions as to where you might start looking for this sort of information.)

Discussion

My list of initial questions looks like this (again, it won't match yours exactly or perhaps even at all, and you shouldn't worry about that):

Why was the Prince of Wales building a palace in Brighton at all?

For what was the Pavilion intended and used, and for how long?

When and why did he choose this style of exotic architecture and interior decor?

Why is the Pavilion ‘Chinese’ on the inside but ‘Indian’ on the outside?

What did everyone think about it at the time?

My second list, of information I would need to collect so as to begin to answer these questions, runs as follows:

Find out about the Prince of Wales – e.g. his other residences, his relations with his father's court in London, where his money was coming from, and where he got the idea for the Pavilion (try biographies, books on court history).

Find out about Brighton and why it had become fashionable at this juncture – at a guess, it must have been fashionable for the prince to have ended up there (start with histories of Brighton, and eighteenth- century, early nineteenth-century and modern guidebooks to the city).

Find out something about the history of the building of the Pavilion (again, try guidebooks old and new and see what leads come up; also see whether rival architects published sketches and ground-plans to support their bids for the work).

Find out whether there were any earlier or other contemporary buildings that were ‘exotic’ in this style. Perhaps there were architects/interior designers who specialized in this sort of work? Possibly as part of a long tradition in such designs? Or was this style a fashion that was echoed across the period in, say, literature and painting? (Try books about architecture, or studies of the Romantic exotic more generally.)

Find out who were the prince's visitors to the Pavilion, and see if they wrote letters or diaries describing their visits. The same might apply for prominent writers who were visitors to Brighton. Check, too, for political caricatures of the prince that might comment on his building of the Pavilion.

What I've just done, as you can see, is to write out a rough programme for research. In fact I followed this programme in order to write what follows, and I hope you will enjoy following me step by step through what I discovered – and deciding whether you agree with my judgements.

This unit is an adapted extract from the Open University course From Enlightenment to Romanticism c.1780-1830 (A207). [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]