4 Self-contained musical structures

Most of the preceding examples, both here and in AA314_1, have been very brief and fragmentary. Now is the time to begin to deal with complete phrases. By ‘complete’ I mean phrases or passages which begin and end in the tonic, and are finished off with a perfect cadence. In other words, they could conceivably pass for entire pieces. The following examples share some basic patterns of voice leading, which will emerge as we analyse them: in particular, the pattern of a linear descent in the treble towards a perfect cadence in the tonic.

For our first example of a self-contained passage, we are going to look at the opening movement of the Sonata in C, K309. In AA314_1 we looked at a passage from the development section of this movement. Now we are going to consider the first subject, presented in the opening bars.

Activity 10

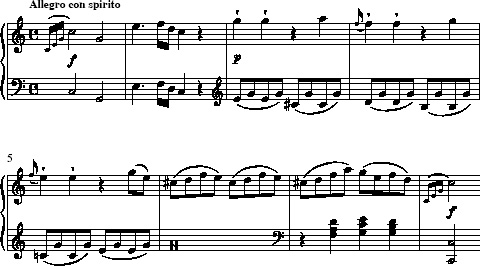

Listen to Extract 8, whilst following the score given in Example 20. How would you describe the structure of the melody line?

Click to listen to Extract 8

Discussion

This opening melody has two main components: a striking, initial motive doubled at two octaves’ distance (bars 1–2), and a more lyrical continuation leading to a perfect cadence (bars 3–8). The initial motive, coupled with the first note (G) of bar 3, outlines an ascending broken chord of the tonic (to use the terminology introduced in AA314_1, this is called an arpeggiation of the tonic chord). Having arrived at this top G, the melody then moves in a descending sequence, similar to the ones you met in earlier examples, arriving at the tonic note, C, in bar 8.

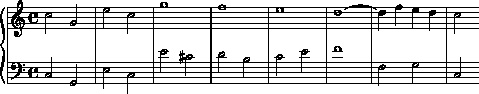

To make these observations clear, Example 21 gives a simplified form of the passage, in which I have removed the inner parts, dissonances and local arpeggiations. I hope you agree that this is a fair representation of the skeleton of the melodic line.

The linear descent in the treble (bars 3–8) should be clear from this version; you will also notice that Mozart delays the arrival of the cadence by prolonging the iib chord (a first inversion D minor chord) for the whole of bar 6. This emphasises the stock iib–V–I cadence.

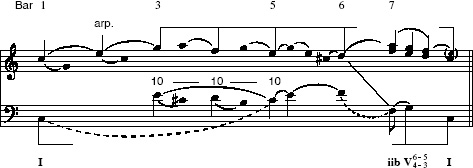

Now I want to produce an analytical graph based on the reduction given in Example 21. I have two main purposes in mind: first, to show the large middleground line; secondly, to illustrate how this basic outline is fleshed out to produce the finished theme. Example 22 is my attempt to do these things.

Activity 11

Compare the graph in Example 22 with the reduction in Example 21, and the score extract in Example 20. How has the melodic structure apparent in Example 21 been shown in the analytical graph?

Discussion

The melodic structure revealed by the reduction has been analysed as two main processes. First, the ascending arpeggiation to the top G (the fifth degree of the scale) is shown via two levels of slurs. Secondly, the subsequent descent from G to C is shown by a beam connecting together the stems of the notes involved. A similar beam shows the overall bass progression, which begins on chord I and moves to a perfect cadence, V–I. The beams connecting these notes together have had to be broken to improve the clarity of the graph – this is solely for ease of reading.

This combination of treble and bass movement is a general feature of virtually all eighteenth-century pieces. While the descent to the tonic in the treble gives the entire phrase its overall contour, the bass, driving to a perfect cadence, affirms the tonal centre and gives the passage a feeling of completeness.

Example 22 has introduced a couple of new notational features. The beam connecting together the notes of the linear descent in the treble is a more effective way of indicating this sort of middleground line than simply using a large slur. The same goes for the beam showing the I–V–I progression in the bass. Beams are usually kept for exactly these situations: large-scale descending lines in the upper parts which aim towards the tonic, or large-scale progressions, also aiming towards a perfect cadence in the tonic, in the bass line.

There is also one new technical term which describes an important aspect of this middleground line in the top voice. The top G at bar 3 is termed the primary tone or head-note of the structure. This term simply means the first note of the main structural line (sometimes the highest note of the piece, but by no means always). In Mozart's works, as in all tonal music, the primary tone will always be consonant with the tonic chord. Here, the A that follows it (the highest note of the extract) is subsidiary, since it is not part of the C major harmony. Indeed, which notes occupy which level of structure depends on the tonality of the extract. Ultimately, the deepest level is based around the tonic chord, precisely because it is the tonic.

Activity 12

Listen again to Extract 8, this time following the graph in Example 22. Can you hear the middleground lines indicated by the beamed notes?

Click to listen to Extract 8

Discussion

In fact, Mozart's sequential pattern in bars 3–5 makes it very easy to hear the underlying descending shape. I hope that you can hear how the whole extract is organised around the drive to the tonic cadence.

It is worth pointing out here that the events of the basic framework have been picked out not because they are necessarily the most interesting, or even the most important things in the music, but because they are the most generalised aspects. All works in the Viennese Classical style tend to drive towards perfect cadences in the tonic, and to move through some sort of linear descent in the upper voice. We saw numerous examples of this in AA314_1. The interesting features which are specific to Mozart lie not in the framework itself but in the prolongational processes between framework and surface, which transform the abstract model into the complete musical artwork.

Before we leave Example 22, I want to look at some features associated with foreground detail.

Activity 13

Compare the graph in Example 22 again with the reduction in Example 21 and the score extract given in Example 20. What aspects of the analytical notation indicate foreground structures?

Discussion

You should by now be fairly conversant with the notation used in this graph. Here are the main elements.

-

Unstemmed noteheads indicate subsidiary notes, connected to the stemmed noteheads by slurs.

-

The figures ‘10–10–10’ indicate an interval progression.

-

The dotted slurs in the bass indicate register transfers.

-

The flagged notehead (which looks like a quaver) indicates a preparation of the dominant chord.

-

The treble notes in bar 7 have been shown as a series of aligned thirds rather than successions.

To spell out how the graph analyses bars 3–5: the sequential descent in the treble is supported by a bass line moving downwards in parallel tenths (E–D–C). At the surface of the music, however, the notes D and C are preceded by their respective leading notes (C# and B).

The changes of register in the bass consist first of a prolongation of the initial tonic, C, via a progression to the C an octave above, and secondly of a straightforward leap from the F in the bass of bar 6 to the F an octave below in bar 7 (the note analysed with a flagged stem). This has the effect of making the cadence take place in the octave in which the bass line began. This octave is called the ‘main register’. To show that the D in the middleground descending line belongs harmonically with this F, I have connected them together with a straight diagonal line. Many pieces establish a main register for the bass line near the beginning, and return to it at the final cadence, an effect which reinforces the sense of return and closure. In these cases, the register is sometimes called the ‘obligatory register’. These terms belong to rather abstract voice-leading theory, however, and are not really our concern in this course.

The flagged note F in the bass (bar 7) denotes a pitch that is not actually part of the middleground framework. It is not strictly necessary to support the second degree of the scale by this iib harmony; Mozart could have gone straight to V. We noted the prominence of this chord earlier, however. It has the special function of driving to the dominant while supporting the D in the upper line. This kind of formula is extremely common in Mozart and is worth committing to memory. [Always remember that the flagged pitch is not a quaver! Here the flag denotes an important event, and it actually occupies a deeper level than the stemmed notes (which look like crotchets).]

You may wonder why I have shown two voices on the upper stave in my analysis of bar 7. In fact, these are miniature, foreground-level unfoldings. My graph states that these voices belong together as ‘treble’ and ‘alto’, although they are presented as a single melodic part. By aligning them in this way, I have clarified the basic harmonic pattern of this bar, the chord progression iib–Ic–V7–I. In order to show that these ‘hidden’ descending thirds imply a resolution to a subsidiary E above the final C, I have placed this note in the graph in brackets. In fact, this note does occur in the music almost immediately after the close of this phrase, as part of the repeat of the initial motive.

It is worth pausing to discuss the chord I have just called ‘Ic’ (bar 73 ). You will notice that I have not called it Ic on the graph itself, and there is good reason for this. While beginners’ books on harmony will often call this Ic, signifying a second inversion of the tonic chord, in fact it contains a fourth above the bass, which is treated as a dissonance. In most tonal music, and almost always in Mozart, this chord (more properly called the cadential 6/4) is expected to resolve to the dominant 5/3 chord (Va). This explains why my sketch shows this progression as a dominant chord with a double suspension (6/4 resolving to 5/3). In other words, the 6/4 chord is not really a tonic chord at all: it is a decoration of the dominant. This extremely common formula has occurred already (it was a feature of both Example 3 and Example 9), and will crop up again in later examples.