2 Melodies within melodies

In this course we introduce two new concepts that are central to voice-leading theory: unfolding and interruption. These, especially the latter, tend to occur at a level beyond the musical surface, in what I have called the middleground. They both involve processes that extend over a longer span of time than the foreground features studied in AA314_1. This course will involve listening especially for musical lines that underpin entire phrases.

You probably think of melody as a single strand of music, maybe moving over a harmonic accompaniment. While this is obviously true in one sense, you may know from the start of AA314_1 that the treble and bass lines also have to make sense as a piece of counterpoint. Dissonances, for instance, are normally treated according to particular rules (a suspension, for example, should resolve downwards by step). Instead of thinking of the opening theme from Mozart's Piano Sonata in B flat, K333 as a tune with supporting chords, I asked you to think of it in terms of voices moving against one another, outlining large-scale lines.

This idea can be taken a step further. In some cases, there is not just one voice, but more than one, within a single treble melody. This idea, that two or more separate lines may be expressed in a single melodic part, is one of the most important aspects of voice-leading theory.

The clearest examples of this device, which is sometimes called ‘pseudo-polyphony’, are found in music of the late Baroque. We are going to look briefly at an extract by Vivaldi in order to see this at work.

Activity 2

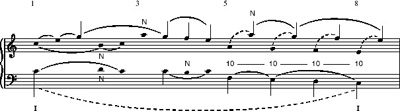

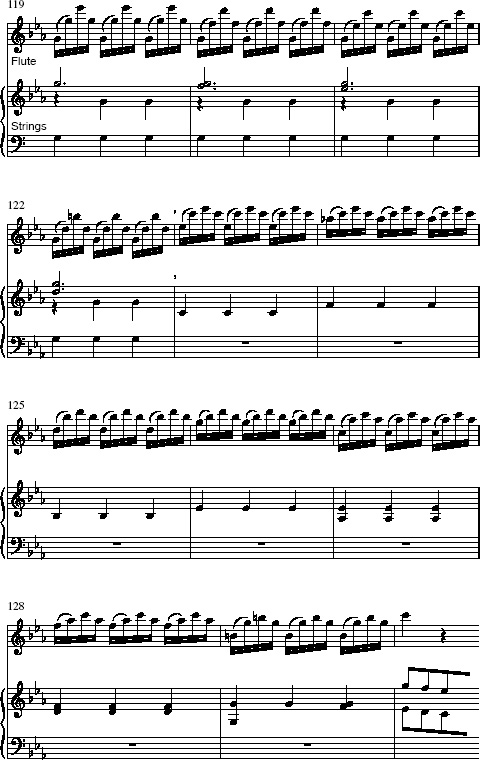

Listen to Extract 2, from a flute concerto by Vivaldi, following the score given in Example 4. How many strands can you hear in the flute's melody line?

Click to listen to Extract 2

Discussion

The giant leaps in the flute part clearly suggest that a multi-voiced melody is at work. In fact, the melody is in three strands. When we hear the passage, the ear tends to connect the upper pitches and hear them as a single line; likewise the lower and middle pitches. These strands are harmonic voices: they move in counterpoint with one another, obeying the basic principles of dissonance treatment. So overall, Vivaldi makes his extremely virtuosic solo line do the job of three lines of counterpoint. If we make a reduction of the flute line, we can see how, on its own, it expresses three contrapuntal parts. The reduction is given as Example 5.

Listen to Extract 3.

Click to listen to Extract 3

J.S. Bach, in particular, exploited this device to its fullest potential. It enabled him to write three-part fugues and other ‘polyphonic’ music for a single melody instrument (the fugues from the three sonatas for solo violin being perhaps the most sublime examples). While the music may contain large leaps at the surface level, the leaps are between different strands which move against one another according to the rules of counterpoint.

Example 6a shows a cadence typical of Bach's practice, slightly adapted from the Sarabande of the Second Suite for solo cello. On paper, the cello part looks almost bizarre: the melody leaps downwards by a fourth, then upwards by a fifth and a seventh. Yet, as always in Bach, the aural effect is supremely logical, since the D resolving to C# in the upper register is supported by A in the bass and E in the tenor: a simple cadential 4–3 suspension.

Activity 3

Listen first to Example 6a, then to the ‘aligned’ reduction shown in Example 6b (E).

Click to listen to Extract 4

Click to listen to Extract 5

This technique is a ‘spreading-out’, through time, of a simpler progression in which the pitches of two or more independent lines actually belong together harmonically. This process, of taking two or more voices and separating them out so as to present them in a single melodic part, is known technically as ‘unfolding’.

This is actually an idea that you have met already. At the end of AA314_1, you made an analysis of the opening of Mozart's Sonata in C, K545. Let's look at this once again.

Activity 4

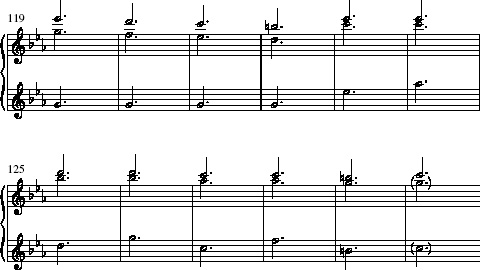

Listen to bars 1–8 of the Sonata in C, K545 (Extract 6), which are shown in Example 7 below, once following the score (Example 7), then again following the analytical graph in Example 8. What does this analysis say about the melody line of bars 5–8?

Click to listen to Extract 6

Discussion

You may recall that in AA314_1, we described bars 5–8 as presenting the descending line A–G–F–E. The graph shows this as two parts moving in consecutive octaves with one another within a single melodic line in the right hand. This is why I said in AA314_1 that it did not matter very much whether you give stems to the notes in the lower or the higher octave. The interval of an octave between each pair of notes is unfolded in the music.

I hope that you were able to hear two lines (A–G–F–E) moving in parallel in these bars. The semiquaver runs that connect each pair of notes can be called miniature ‘octave progressions’, or ‘8-prg.’ for short. We might call these lines a sort of ‘treble’ and a sort of ‘alto’. This would not really be quite right here, though, because rather than moving in counterpoint like the earlier examples from Vivaldi and Bach, these lines are merely a doubling of a single voice at the octave. This technique is quite common in Mozart's sonatas. It is not an example of contrapuntally incorrect ‘consecutive octaves’ but a good (if simple) example of how two or more voices can exist within a single melodic line.