2.2 The rise of the Celts

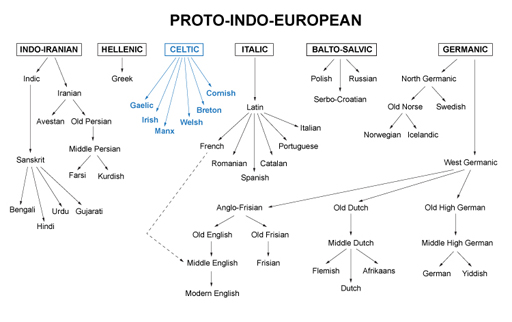

The majority of Europe’s languages, including Gaelic, belong to a family known as Indo-European, so labelled because it includes most of the tongues of South Asia (with the exception of southern India), as well as Europe. Until a major expansion from the 15th century onwards, including the creation of overseas empires, these languages were largely restricted to Europe and southern and western Asia. Now they have a global distribution, with almost 3 billion native speakers and include some of the world’s most populous languages, such as Spanish, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, German and French.

Within the Indo-European family, there are several subgroupings identified by linguists. For example, English, Dutch and Norwegian belong to the Germanic subgroup, French, Italian and Spanish to the Italic subgroup, with Russian, Slovak and Polish being classified as Slavic tongues. One of the subgroups is Celtic, which contains the six living Celtic languages – Gaelic, Irish, Manx, Welsh, Breton and Cornish – and some that are now extinct e.g. Gaulish, Galatian, Celtiberian, Pictish and Cumbric.

The earliest records of the Celts date from around 500 BC, when Greek texts referred to peoples to their north as Keltoi. The Latin term was Celtae, used of tribes and nations now understood to have been Celtic-speaking. The term was at this stage restricted to continental peoples.

The use of Celtic in relation to peoples of the British Isles dates from the 17th century when the linguist Edward Lhuyd made a comparative study of Welsh, Gaelic, Irish, Cornish and Breton, and established that these were related to each other and also to the extinct language of Gaul, which was indisputably Celtic.

For example the Gaulish mapos (‘son’) has its equivalent in modern Welsh mab and the Gaelic mac; the Gaulish tarvos (‘bull’) is closely related to the Welsh tarw and the Gaelic tarbh.

The following table shows some words in Gaelic, Irish, Welsh and Cornish which would appear to share a common origin (in a common Celtic ancestral language):

| Scottish Gaelic | Irish Gaelic | Welsh | Cornish | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aimsir | aimsir | amser | time, weather | |

| anail | anáil | anadl | anall | breath |

| cath | cath | cad | kas | battle |

| caol | caol | cul | cul | slender |

| cnò | cnó | cneuen | know | nut |

| creamh | creamh | craf | wild garlic | |

| cù | cú | ci | ki | dog, hound |

| làn | lán | llawn | leun | full |

| roth | roth | rhod | ros | wheel |

| taigh | teach | ty | ti | house |

| troigh | troigh | troed | troes | foot |

The continental Celts were not a politically unified people – there was no such thing as a Celtic empire – but Celtic-speaking peoples, sharing some degree of common culture, lived across a wide swathe of Europe. They left virtually no written records so our knowledge of them comes largely from the Greeks and Romans, from the archaeological record, and from the place names they left behind.

The first Celtic culture to emerge, around the 8th century BC, is associated with finds made near the Austrian village of Hallstatt and is known as the Hallstatt Culture.

Excavations provided evidence of a rich material culture and trading links to the Mediterranean world. Around the 5th century BC, we see the emergence of the La Tène Culture, named for excavations made at La Tène in Switzerland.

This was also Celtic and appears to have been more expansive in nature; decorated metalwork of La Tène style have been found in Britain and Ireland, for example.

It is uncertain what languages were being spoken in the British Isles at the time, but it is likely that Celtic was already among them. By the 3rd century BC, the Celts had spread across a large part of continental Europe, from modern Portugal to Belgium and Germany, into northern Italy, through the Danube basin and even down into Turkey.