6.5 Sports and pastimes

Scotland, including the Gaelic-speaking areas, has a very rich tradition of games and pastimes which were a crucial part of life, both in urban and rural environments. They were important elements of young people’s lives and preceded the introduction of more formalised and regulated sports in the late 19th century.

These games and pastimes were often linked to the seasons or to specific times such as New Year, Christmas and other special occasions. They were games of chance and skill, of contest and forfeit; they involved ghosts and witches, courtship and marriage divination and well worship; gambling, feats of skill and strength, ball games and dance games.

Many of them involved singing, chanting or clapping, and their musical content very likely forms a basis for many traditional songs and tunes.

A number of significant collections and publications exist, detailing the wide range of games and pastimes and a number of organisations such as the Folklore Society and The School of Scottish studies at Edinburgh University have done important work in preserving the rich store of activities, including variations of the same games as interpreted and passed on throughout the country.

The Statistical Accounts of Scotland are an invaluable source of information on games and pastimes in the 19th century.

Box 7 Some games and pastimes

Cluich an taighe (‘The Home Game’)

Played with three circles 60 yards apart; participants gather in one of them; and one other person outside with a ball. The person with the ball tries to hit the others while passing between the circles making them ‘prisoner’.

Stracair

A bat game played by opposing teams with the aim to get a ball (ball-speil) into a hole in the ground.

Iomairt air a’ bhall

Played with a ball thrown against a wall, players assuming names; when name is called, designated player has to try and catch it before it hits the ground; if player fails to catch it he/she then has to avoid being hit by the player who threw it at the wall.

Iomairt air a’ gheata

Played with a bat or thick stick two against two. The game involves striking a small stick trying to get it into a ‘cailleach’ or hole; the other two players protect the ‘gate’; sometimes called Cat and Dog or Cat and Bat.

Iomairt air an Stainchear

A version of rounders or ‘bases’ with the name possibly derived from the English stanchel (stanchion/a station/upright/support). The bat is shaped like a cricket bat, the ball made of yarn, wound round a cork centre.

Shinty

Among the sports which came of age and began to be regulated in the 19th century, shinty was undoubtedly the most important to the Gaels.

Shinty - iomain or camanachd in Gaelic - was probably introduced to Scotland along with Christianity and the Gaelic language nearly two thousand years ago by Irish missionaries. The game, or some similar version of stick and ball activity, has been played through time virtually UK-wide, from the more hospitable and gentler plains of the Scottish Borders; from the Yorkshire moors to Blackheath in London, to wind-swept St Kilda as the intrepid traveller Martin Martin described on his epic voyage round the Hebrides around 1695:

‘They use for their diversions short clubs and balls of wood; the sand is a fair field for this sport and excercise in which they take great pleasure and are very nimble at it; they play for some eggs, fowls, hooks and tobacco; and so eager are they for victory that they strip themselves to their shirts to obtain it.’

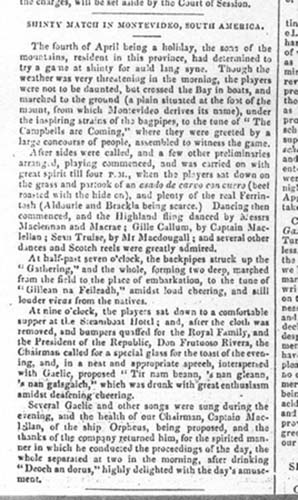

Shinty world-wide

Shinty is a game of great antiquity and is strictly amateur. It is linked (not always with complete accuracy) to golf and ice hockey, and is also to be found in a much wider space from the plains of Montevideo in the mid-nineteenth century, to Toronto and Canada’s Maritime Provinces; from the blistering heat of New Year’s Day in Australia over 150 years ago, to Cape Town and also the war-ravaged wastes of Europe through two World Wars. There is now a burgeoning group of players and clubs in the United States of America.

Origins

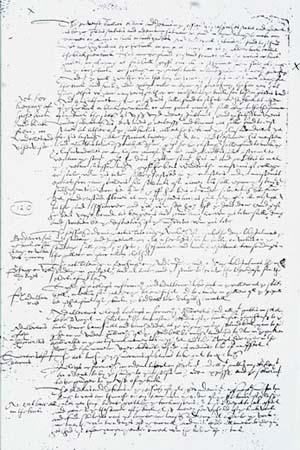

There is no doubt but that shinty (or more accurately, some early form of the stick and ball game) was played in pagan times. In Scottish terms, the earliest written reference to shinty or ‘schynnie’ is in 1589, in the Kirk Session Records of Glasgow. This is reproduced in full below. The passage of interest (which is marked with an X) reads:

‘that nane be fund castand stanes wi th in the kirkis zardes, or playing at futeball, goff, carrick or schynnie’ (Kirk Session Records, Glasgow, 16th October, 1589)

The Book of the Club of True Highlanders, published by the Society of True Highlanders in 1881 regarded shinty as being ‘undoubtedly the oldest known Keltic sport or pastime….The origin of this game is lost in the midst of ages... ….played by Noah himself; and if by Noah, in all probability by Adam and his sons.’

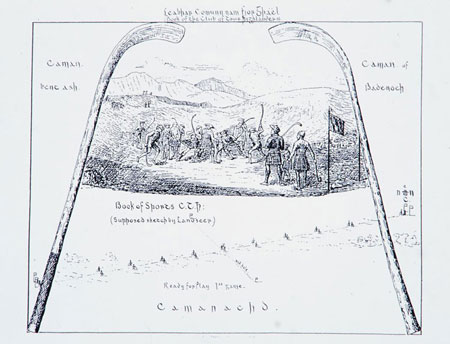

The word ‘shinty’

The term ‘shinty’ itself requires some explanation. Iomain, or more latterly camanachd, were the Gaelic terms, meaning driving. ‘Shinty’ (or its variants shindy, shinnie, shindig etc), however, has proved much more contentious, and the general view is that it is derived from the Gaelic sinteag – a ‘leap, bound’. Shinnie, in fact is held to be the older of the two (around 1600) with shintie replacing it some 100 years later.

Shinty’s part in festivals

There was no event of greater importance in connection with the celebration of the advent of the New Year in the Highlands than the New Year’s Day Shinty Match. Very often ‘A cask of whisky strong’, was the victor’s prize. These contests were often between two districts or parishes, with no limit to the numbers taking part (as many as 2,000 men engaged), from the forenoon until darkness fell. Occasionally a hogs-head of whisky was given to the winners by the proprietor.

One of the best sources for determining shinty’s ‘place and space’ is the dictionary. In Jamieson's Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language we find shinty sandwiched between ‘Shinnock’ and ‘Shiolag’. Perhaps more surprisingly however, the English Dialect Dictionary (EDD) records shinham in the north of England, shinnins and shinnop in Yorkshire, and shinny and shinty in the north of England generally, and as far south as Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Gloucestershire. The dictionary mentions shinty being played in Workington in Cumberland as late as 1888, when two boys were fined for playing the game in the street and a third ‘was let off, having been well thrashed by his parent’.

Shinty’s place in society

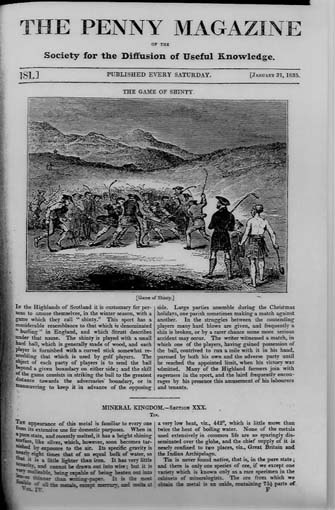

Shinty was of much wider interest than just being the expression of some local conflict, or a landlord’s patronage. The Penny Magazine of January 31, 1835, produced by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge provides us with a useful visual representation of shinty as it was perceived at the time.

Shinty beyond the Scottish border

Shinty was not confined to the Highlands, or even Scotland. The first club established in England was Cottonopolis, Manchester, formed prior to December, 1875. The pages of the Highlander newspaper, particularly in the late 1870s and early 1880s, read more like an account of English Premier league football matches with details of games and frequent references to Birmingham, Manchester Camanachd, Old Trafford, the Highland Camanachd Club of London, Cottonopolis, Bolton, Nottingham Forest and Stamford Bridge.

There was feverish activity in shinty terms on both sides of the border, and across the world from the Cape of Good Hope to Australia and New Zealand; from Toronto in Canada, to New York, where a team was formed in 1903.

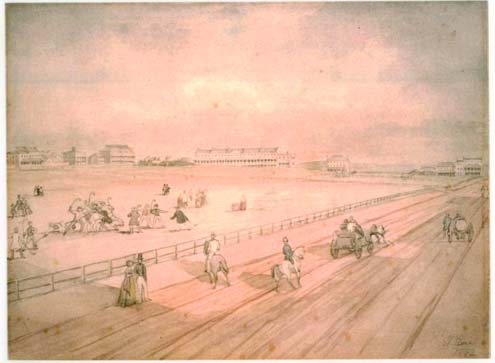

Perhaps the most convincing evidence of shinty’s translation to Australia is a water-colour painting by the Scot John Rae in 1842.

The scene depicted appears to show shinty being played. It is one of a series painted by Rae, a Scotsman who apparently arrived in Sydney in December, 1839, a year after the ‘St George’, the vessel which left Oban in 1838, packed with Badenoch folk, and for which the famous Gaelic song ‘Guma Slàn do na fearaibh’ (‘Good health to the fellows…’) was composed. These are the words as printed by Thomas Sinton in The Poetry of Badenoch, Inverness, 1906.

A health to the fellows, Who’ll cross o’er the sea! To the country of promise, Where no cold they will feel.- A health to the fellows, Who’ll cross o’er the sea! A health to the goodwives! We’ll hear no complaining; They’ll follow us heartily Over the sea. And the beautiful maidens Going with us together,- They’ll get husbands to marry, Who’ll give ear-rings of gold. | Gu 'm a slàn do na fearaibh Thèid thairis a' chuan Gu talamh a' gheallaidh, Far nach fairich iad fuachd. Gu 'm a slàn etc. Gu 'm a slàn do na mnàthan Nach cluinnear an gearan, 'S ann thèid iad gu smearail, 'G ar leantuinn thar 'chuan; Gu 'm a slàn etc. 'Us na nìghneagan bòidheach, A dh'fhalbhas leinn còmhladh, Gheibh daoine ri'm pòsadh, A chuireas òr 'nan dà chluais. Gu 'm a slàn etc. |

Shinty in Australia

It should come as no surprise then when we find that in Geelong, Victoria, a society was established by Highlanders to maintain the culture and traditions of their people. ‘Comunn na Feinne’ (The Fingalian Society) lasted from the 1850s to the 1940s and featured shinty at its New Year gatherings, particularly in its early years.

Shinty’s retreat

Shinty is often regarded as having retreated to the Gàidhealtachd (Highlands of Scotland) by the nineteenth century. From there it was re-introduced to the Lowlands by people who were encouraged or forced to move south. The children at New Lanark played and there was an active shinty club in the Vale of Leven in the 1870s; certainly it was Highlanders in exile who played in the matches which were held in Glasgow and Edinburgh, and much further afield, from the 1870s onwards. In 1816 members of the Burgess Golfing Society complained that their play on Bruntsfield Links was being made hazardous by shinty players.

There is a significant corps of visual evidence confirming shinty’s existence in the city at the same point. A large watercolour painting by Charles Altamont Doyle (1832-93), which is held in the National Museum in Edinburgh depicts an area of the city, Duddingston Loch. The scene shows a crowd of adults playing three sports, shinty, curling skating. Contemporary press reports in 1876 indicate some 6,000 may have been present.

Shinty in universities

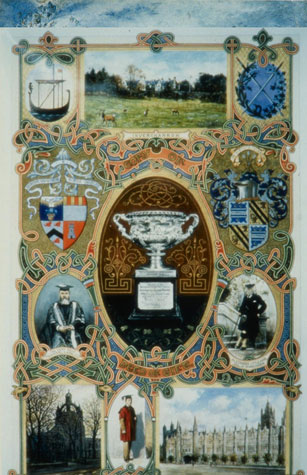

One of the finest historical expositions of shinty and its context, as well as Gaelic vocabulary, is by the famous scholar Alexander MacBain of Inverness who produced it for Alexander Littlejohn, a Londoner of Scottish origins who donated the fabulous Littlejohn trophy and album to the University of Aberdeen, for play between student teams from Scottish universities.

Shinty in the 21st century

A series of hugely interesting and memorable exhibition matches 100 years ago were the immediate catalyst leading to the formation of the Camanachd Association, shinty’s ruling body. The game has developed from a series of loosely organised clubs and structures, into a progressive organisation with around 50 clubs of varying strengths competing on a regular basis, commanding national media attention and significant sponsorship.

Shinty has approximately 2,000 players (men, women and children) and between 2,500 and 3,000 members of the Camanachd Association, with teams playing at various levels from primary school age to senior (adult). In Ireland, the Gaelic Athletic Association, a multi-million pound business, runs an organisation of over 200,000 players – a ratio of 100 hurlers for every shinty player. However, Scotland has consistently managed to compete with Ireland in the modern series of full international matches in the compromise game of shinty/hurling.

Shinty as a national asset

Shinty in its organised form has come a long way as an organised sport. However, the continuing dilemma is whether to promote the ancient sport of the Gael as a modern, vibrant game, or to preserve it as a quaint aspect of Highland culture. It has, after all, survived the ravages of two World Wars and has also seen off the many economic disasters – past and more recent – which have beset the Highlands. The falling birth-rate and school closures are but another historical affliction.

Shinty’s players and administrators regard their sport as one of the greatest games in the world. Shinty is also one of Scotland's truly national - indeed international - assets, which has an important, and hitherto largely ignored place in the space of world sport. For too long now historians, and particularly sports historians, have at best under-valued, at worst ignored, shinty’s rightful place and space in world sport.