2 Asking someone for something: the core skill

A simple question goes to the very heart of your work in winning resources and support: how do you ask people for something? You are fundamentally in ‘the asking business’ – so what are the core processes and skills of asking?

‘Making the ask’ is a phrase which is often used to describe this absolutely vital feature of your work. Your work may involve all sorts of activities. But your success and effectiveness in securing resources and support will be very limited if you do not, in the midst of everything else, actually ‘make the ask’.

This section deals with what is involved in making an individual, person-to-person request for a donation or some other form of support. It has two purposes. The first is to identify the main personal skills and competences involved in asking for things face to face. The second is to map out the essential ingredients of the asking process which will serve, in the next section, as a framework for understanding what you need to do when you are making requests and appeals – at a distance – to a large number of people.

Many of us feel awkward and diffident about asking people for things. It often seems unduly intrusive. It flies in the face of the accepted conventions of polite, interpersonal behaviour. To begin to get a hold on the business of being confident and effective in asking individuals for support, think about your own feelings and approach.

Activity 1a

(a) Consider each of the following requests. Which would you feel confident about and which would you feel uneasy about?

| Confident | Uneasy | |

|---|---|---|

| Asking a member of your family for a loan of £10 | ||

| Asking a member of your family for a loan of £5000 | ||

| Making a house-to-house collection for a national charity | ||

| Making a house-to-house collection for a local hospital | ||

| Asking your immediate colleagues to donate to the leaving present of a popular subordinate | ||

| Asking a local business to contribute to the purchase of a minibus for your child's school | ||

| Asking a meeting to donate to a pressure group of which you are a member | ||

| Phoning someone ‘cold’ (that is, knowing nothing about them other than their name and phone number) to ask for a donation of £50 | ||

| Taking a long-standing contributor to your organisation out to dinner to ask her to leave your organisation something in her will |

Answer

Reasons people commonly give when asked why they are confident or uneasy when asking for money:

Confident:

I know who I am talking to and how they are likely to respond.

I believe strongly in what I am asking for.

I know exactly what I am asking for and why.

I never ask for more than someone can afford.

I like talking to people – however fleetingly.

Without learning to ask, we simply would not have been able to have an orchestra.

I try to be as honest and open as I can – and not pretend that I am more confident or sure than I am.

If you don't harangue people or use moral pleading, then the vast majority of people are quite nice and enjoy being able to contribute.

I found I could handle this asking business as soon as I stopped expecting that everyone ought to agree with me. I always try to respect their right to say no to my request.

Uneasy:

I am unsure of my own commitment. I always feel that I am conning people.

I am afraid people will say no.

I don't like getting into arguments.

I don't like being rejected.

I basically don't agree with asking for money for social welfare; I think its funding should come from taxation.

I feel I am intruding on people's privacy.

I know it sounds funny, but I think we ought to be able to manage on what we've got already.

I don't like rich people – they make me feel angry and uncomfortable; and I don't think we should ask poor people.

It's just begging on a large scale and I find it is demeaning to me and the people I ask.

As a disabled person I want rights not charity.

I can't get rid of the sense that I am a second-hand car dealer.

Activity 1b

(b) Make a note in your Learning Journal of the three or four main reasons why you would be confident about making some sorts of request and uneasy about others.

Answer

Having mixed feelings about asking people for money and other forms of support is not something peculiar to you. You are putting yourself in a position of risk and personal exposure. On the other hand, just because you feel you lack the blend of charisma, eloquence and general confidence of the stereotypical fundraiser, you should not classify yourself as the sort of person who cannot ask for things. As the comments in the answer to part (a) suggest, handling a mixture of confidence and anxiety is common.

There are two related ways in which you can deal with such tensions and conflicts and begin to develop your own ability to ask for resources and support. The first is rooted in your performance and highlights some of the key behaviours of asking; the second starts from an understanding of the overall process you are engaged in.

As far as the former is concerned, Box 1 summarises some of the accumulated wisdom about how to organise your own behaviour as you conduct an interview with a ‘prospect’.

Box 1 How to ask someone directly for a mjaor contribution

Make it a special occasion – It's worth thinking carefully about the setting and timing of any request for major support.

Dress appropriately – Respectful, non-verbal communication is an important part of the process of asking.

Set yourself and your prospect at ease – Remember that this request is in the context of a relationship. Always allow some time for you and your prospect to settle yourselves into the encounter.

Establish some form of mutuality – Pay attention to your prospect's motives, aspirations and concerns. There may be some which you feel they ought to have but which they actually lack. It is important to acknowledge difference and their right to be who they are and, at the same time, to establish a basis of common interests.

Explain who you are – Be very clear about what you and your organisation do and do not do. Be proud of its accomplishments. Be specific. Do not apologise for wanting a financial contribution. Invite and answer questions. Be businesslike.

Ask for a specific amount of money – Make a precise request along the lines of ‘I would like you to contribute £1000 to the museum.’ Then remain silent! It is right and proper not to hustle your prospect and to allow them time and space to reflect on your request. If an uncomfortable amount of time passes, ask your prospective donor whether they have any questions.

Listen and respond appropriately – You must listen carefully to what is being said. If the response is indefinite, work on the relationship and present your case more carefully. Empathise with their concerns but stay on track by continually bringing the conversation back to your cause. Reiterate the importance of a contribution. If the response is positive, restate what has been promised to make sure you have understood it correctly. Make a written agreement there and then – do not leave your prospect to contact you later, they rarely will. If the response is negative, listen and clarify the reasons respectfully. It may well be that you can make a further approach another day with a different request to which they will respond positively.

Always say thank you – Where possible, send a personal thank-you letter within forty-eight hours, no matter what you receive. Reinforce the relationship that has been created and repeat the value of the donation.

Activity 2

(a) Choose one of the requests you felt uneasy about in Activity 1(a). Using the points in Box 1 as guidelines, make a brief plan in your Learning Journal of how you might conduct an interview with a ‘prospect’.

(b) Make a note of what you see as the strengths and weaknesses of looking at your performance in this way.

Discussion

Developing your confidence and skills along these lines is one of the strengths of the behavioural approach to asking for donations and support. It gives you more choices. A potential weakness would be to use the procedures outlined in Box 1 as a mechanical formula.

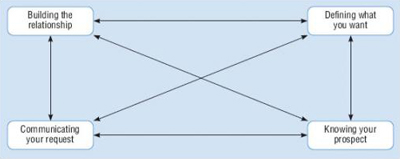

The second approach to asking – the process approach – does not provide a ‘recipe’ to follow in the same way. It sees asking as a creative activity: creating a suitable opportunity for someone to give. It is based on four key aspects of the process of asking, but without presenting these as a series of steps. The business of asking is essentially relational and interactive. Figure 1 and Box 2 summarise the continual interplay and adjustment between the four aspects.

Box 2 The process of asking

Each of the elements in Figure 1 involves you in making judgements and identifying options in the light of the information you are receiving.

1 Knowing your prospect

You do not have to be personally acquainted with a prospect before you can ask for anything. But you have to make some preliminary attempt to assess how they are likely to respond, the sorts of things they support and the sort of donation you think it would be feasible to request. This is not just a matter of detailed, initial research. Someone collecting for a ‘green’ organisation outside a supermarket on a Saturday morning is continually making quick judgements of people based on eye contact, what's in their trolley, what they are wearing, and so forth. These signals will contribute to some sort of initial assumptions about reasons for responding to any request for support.

2 Defining what you want

You need to be specific about what you want from an individual prospect and why you want it. You will have to indicate a level of donation or a type of involvement, and the reasons you believe it merits your prospect's consideration. Offer the scope for your prospect to explore, discuss and negotiate. What you are looking for is a request which they can define and respond to in ways which are appropriate and meaningful to their needs and concerns.

3 Communicating your request

There is no one ideal way of actually putting a particular request. Communicating your request involves thinking through how your proposal is likely to be received and amending your style if necessary. Link your request with other information and requests your prospect might have received from your organisation. Indeed, you should also consider whether you are necessarily the most appropriate person to make the request. Someone who ‘speaks the same language’ as your prospect and personally shares his or her values and concerns will often be most effective.

4 Building the relationship

You need to create – or sustain – an appropriate relationship. How far are you asking your prospect simply to slot into a standard relationship – as member, occasional or one-off contributor, long-term supporter, benefactor – or what is the scope for an individual negotiation of the relationship in the light of his or her concerns and aspirations? Although the request may be for a specific purpose, you will want to create a basis for both of you to develop the relationship further.

There is much common ground between the performance and the process approaches to asking for support from a potential contributor. You can use either or both as a basis for planning and reviewing the way you make specific requests. In practice, you have or will develop a style and approach with which you are comfortable. But however you ask, one other feature of one-to-one asking still has to be considered.

A superb personal performance and a flawlessly sensitive and flexible process will not guarantee you the outcome you seek.

This is not your fault, nor the fault of the prospect. Even if fundraising uses terms such as ‘prospect’, you are not in the technical business of oil exploration. You are engaged in a much more fragile business of fostering new relationships and identities. You are asking people to change, to be a bit different, to adjust their ideas of themselves. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that many people are not always prepared to make these changes just because you ask them and when you ask them.

It is in the nature of this sort of work with individual donors and supporters that you will often fail – or not succeed immediately. Arguably, the most important skill you need in this interpersonal area of work is the ability to handle the answer ‘no’ and yet still continue. While you need to have a strong personal commitment to the success of the individual request, you also need to place it firmly in the context of the bigger picture. Concentrate on learning from the experience. The person whose donation you are soliciting is an individual amongst many other possibilities. Furthermore, it is important to maintain a sense of potential change and development. In the words of a successful appeals manager: ‘“No” today does not imply “No” tomorrow. I always try to retain the relationship.’