1 The importance of energy use in buildings

Appreciating the importance of energy use in buildings requires a look at UK national energy statistics. These use two categories of energy:

- Primary energy − this is essentially energy in its ‘raw’ form. Examples include crude oil before it is refined and the fuels used to generate electricity: coal, natural gas and nuclear heat.

- Delivered (or final) energy − this is the energy that the consumer actually receives (and pays for): refined petrol and diesel, mains electricity, piped natural gas.

The statistics also split energy use into different sectors: the domestic sector − people’s homes; the services sector – shops, offices, schools, etc.; transport and, finally, industry.

Box 1 Energy units

Perhaps the most familiar energy unit is the kilowatt-hour (kWh). Household gas and electricity bills are normally expressed in these. In electrical terms this is the amount of energy used by a 1 kilowatt (kW) appliance, such as a small electric fire, in one hour.

The prefix ‘kilo’ means 1000 and is shortened to ‘k’. 1 kW = 1000 watts.

Most of the energy calculations in this course are in watts, kilowatts and kilowatt-hours.

Energy statistics may use a ‘scientific’ unit of the ‘joule’ (J). This is the (tiny) amount of energy used by a 1 watt device in 1 second. 1 kilowatt-hour = 3.6 million joules.

Larger energy units use other prefixes. Those used in this course are:

mega – shortened to ‘M’. 1 MJ = 1 million joules and 1 kWh = 3.6 MJ

giga – shortened to ‘G’. 1 GJ = 1000 MJ

tera – shortened to ‘T’. 1 TJ = 1000 GJ

peta – shortened to ‘P’. 1 PJ = 1000 TJ

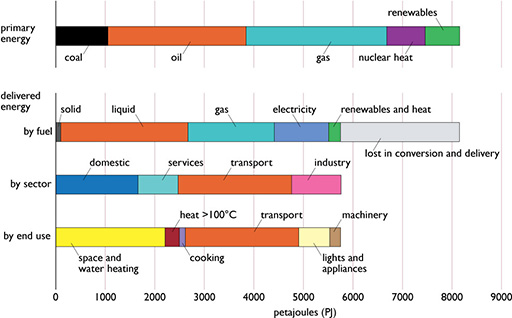

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of UK primary and delivered energy for 2015 in different ways. The top bar shows the actually primary fuels used. The three bars below show the delivered energy use expressed in three ways: by fuel, by energy sector and by end use.

Note that although UK primary energy consumption in 2015 was about 8200 PJ, the delivered energy use was less than 6000 PJ. As shown in the second bar of Figure 1, there were losses of about 2500 PJ ‘in conversion and delivery’. Most of this is waste heat rejected from power stations in cooling towers or into the sea. Typically generating 1 kWh of electricity in a conventional thermal power station requires between 2 and 3 kWh of primary energy input.

It can be seen in the third bar that the delivered energy use in the domestic and services sector is about 2500 PJ. This is almost entirely consumed within buildings. Adding the fraction of industrial energy use that is also used in buildings means that ‘energy in buildings’ makes up almost half of the UK’s delivered energy use. The domestic and services sectors also account for over 60% of the UK’s electricity use. When this and its attendant generation energy losses are taken into account, buildings are responsible for nearly half of UK primary energy use and about 30% of national greenhouse gas emissions (CCC, 2017).

Energy use is, of course, only the means to provide various energy services. The real task is to provide these at a lower energy and environmental cost. The energy services in buildings include:

- the provision of comfortable homes and working environments

- hot water for washing

- cooking food

- safe chilled food storage

- adequate lighting for homes and offices

- the ability to use electronic equipment for communication and entertainment (and producing and studying material such as this course).

The fourth bar of Figure 1 shows that over 2000 PJ of delivered energy were used for space heating (i.e. warming the internal spaces of buildings) and water heating. These applications only require low temperature heat (i.e. less than 70°C). Space heating is a prime target for energy efficiency programmes.

There is a considerable potential for using some of the low temperature waste heat from power stations for heating buildings using combined heat and power generation (CHP), as is widely done in countries such as Denmark.

Of the energy use in buildings about two-thirds was used in the domestic sector and about a further 20% in the services sector.

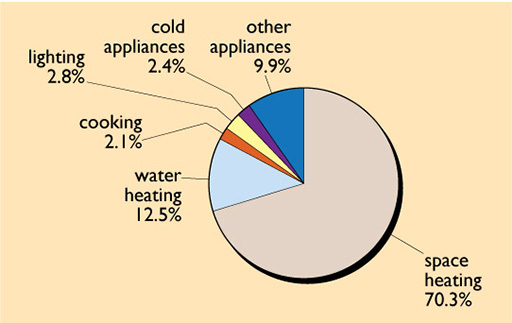

Within the domestic sector there is a familiar range of energy uses (see Figure 2).

In 2016 about 70% of the delivered energy was used for space heating and 13% for hot water. While these particular figures have only changed slowly over the past 40 years, the amount of electricity for ‘other appliances’ (e.g. radios, TVs, computers and other electronic devices) has increased by a factor of more than five. Given that the domestic sector accounts for 30% of UK electricity demand this is a matter of concern and is discussed in Section 4.1.

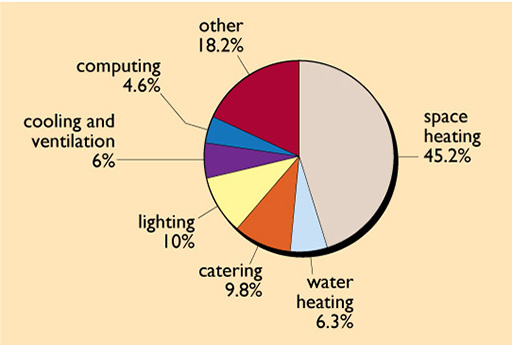

The services sector contains a wide range of different buildings such as offices, schools, shops and hospitals. Although just over half of the delivered energy was used for space heating, this sector uses large amounts of electricity, about 30% of UK demand. A large amount of this is for lighting (see Figure 3) – in retail premises (i.e. shops) about 20% of the energy use in 2016 was for lighting.

Activity 1

In 2016 which sector used more electricity for lighting: the domestic sector or services sector?

Answer

In the domestic sector lighting made up 2.8% of 1730 PJ total energy use, i.e. 48.4 PJ.

In the services sector it made up 10% of 810 PJ, i.e. 81 PJ, over 50% more than in the domestic sector.