2.1 The goals of interaction design

Generally speaking, any interactive product should provide good usability. But what do we mean when we say it is ‘usable’? Over the years interaction designers have identified a number of specific qualities, which are aimed at during the design process and referred to as 'usability goals. Typically, these are:

- Effectiveness: does the product enable the user to easily accomplish the task for which it is designed?

- Efficiency: does the product enable the user to accomplish a task quickly with a minimum number of steps?

- Safety: does the product minimise opportunities for users to make errors and, if they do make errors, can they recover easily?

- Utility: does the product offer the functionalities that users need to complete a particular task?

- Learnability: is it easy to learn how to use the product?

- Memorability: is it easy to remember how to use the product?

The above usability goals are all quite different, emphasizing different aspects that we aim for in a design. Here we want to highlight a number of key points about usability goals in general:

- Measurable goals. Compared to the general concept of usability, usability goals are more specific – and can be assessed and measured, thus helping you to work towards good usability in specific cases. So when thinking of assessing or aiming to improve the usability of the products you design, your focus should always be on these more specific goals. In the example of the Smart Glass discussed in Section 1, designers could set a safety goal that users must be able to hold the glass securely without dropping it. To see if the goal is met, they could measure how many times (if any) the glass slips from the users’ hands during a given period of time.

- Goals must be prioritised. While all usability goals are relevant to all interactive products, it is not always possible, nor desirable, to achieve all of them in equal measure. For certain products, some of the goals are more important than others and will need to be prioritised.

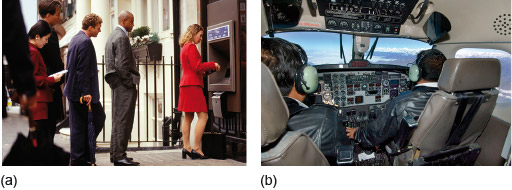

Think, for example, of the interface of an ATM (automated teller machine – Figure 13(a)); anyone, regardless of whether they have technical skills or whether they have used ATMs before, needs to be able to engage successfully with the interface straight away. Therefore, the most important goal for an ATM is that it needs to be very quick and easy to learn to use.

On the other hand, flying a plane (Figure 13(b)) is a much more complex task and, consequently, the plane’s control panel is correspondingly complex; planes are also only flown by highly-specialised users who have received considerable training and fly planes regularly. In this case, learnability and memorability are not the most important requirements: instead it is more important that the control panel allows the pilot to carry out complex tasks efficiently and, above all, safely. Indeed, when it comes to safety-critical tasks, such as flying planes, safety has to be prioritised over efficiency, although the two are linked and efficiency can help improve safety.

- Meeting goals may be challenging. The characteristics of users, their activities and the context in which they operate can make it challenging to achieve certain usability goals, while making it particularly important to achieve those very goals.

For example, in Section 1 Activity 3 we saw how, in the case of one blood infusion pump, the pressure under which nurses work and the environmental distractions to which they are exposed made it very easy for one of them to make a fatal error (Figure 14). Instead of making the pump extra safe to use under those conditions, tragically the pump’s interface had allowed the nurse to set the pump to deliver an overdose and had failed to alert her to the error. Cases like these demonstrate how certain usability goals may be very important; designers must recognise their importance and make an extra effort to ensure that these goals are prioritised and met.

But great interactive products do not just provide good usability, they also provide good user experience – that is, they not only enable their users to do what they want to do, but they do so in a way that feels good and enriches their users’ lives in one way or another. Desirable qualities related to user experience, which interaction designers might aim to provide for prospective users, include motivating, exciting or enjoyable; while undesirable qualities that interaction designers might aim to avoid include boring, frustrating or unpleasant. Bear in mind that the list could be as long as the list of positive or negative adjectives that might describe one’s range of emotions.

Indeed, there is a key difference between usability goals and user experience goals. On one hand, the extent to which usability aims have been achieved is relatively easy to assess by measuring aspects of a user’s performance while interacting with a product or prototype. Examples include whether a past user can remember the sequence of steps required to extract cash from an ATM; how quickly a pilot can perform the task of redirecting a plane; or how many errors a nurse makes when setting a blood infusion pump, whether they notice the errors and how easily they can recover. This makes usability criteria relatively objective and therefore easier to design for.

On the other hand, the extent to which user experience goals have been achieved is more difficult to assess objectively, precisely because it has to do with the users’ feelings rather than with their performance. Therefore, interaction designers tend to assess the users’ experience via subjective measures – for example, by asking the nurse whether they felt uncertain or frustrated when trying to set the blood infusion pump. This makes user experience criteria relatively more challenging to design for.

However, it is important to remember that, whether we talk about usability or user experience criteria, ultimately everything about an interaction with a product contributes to the experience of the user. A product with poor usability cannot provide a good experience. Equally, a product that does not provide a good user experience may as a result be less usable.