8.1.3 Affordance

A third key design feature for usability is affordance – this more difficult concept is related to the functions that a product offers, or affords, to its users. Some affordances are real – for example a handle on a portable machine. Some are perceived affordances – these can be more relevant in computerised products, which have more complex and dynamic means of interaction with the user. For these products, it is important for the designer to help the user to perceive just what functions the product affords. Donald Norman defines affordance as:

Strong clues to the operation of things … When affordances are taken advantage of, the user knows what to do just by looking: no picture, label, or instruction is required.

For many common types of controls on machines, we expect that certain actions, such as turning or sliding them in certain directions, will produce expected kinds of results. Expectations that are found to be widespread in a population are know as conventions or stereotypes.

Example

Consider the arrangement in this example; which way would you turn the knob to make the pointer on the dial rotate from 1 to 6?

Answer

You would almost certainly say clockwise, because the mechanism here takes advantage of two strong conventions. It is normal to expect the pointer to move in the same direction as the knob. Also, people tend to associate clockwise rotation with the actions of on and increase, such as with the on-off volume controls of a radio.

There are, however, situations in which these conventions are reversed. For instance, in which direction do you turn on a water tap? It is usually anticlockwise, yet I'm sure you don't think every time you turn on a tap that it works in reverse. Generally speaking, the convention is usually anticlockwise for on when dealing with fluids and gases, and clockwise when dealing with mechanical and electrical devices. But there are many variations. For example, a pair of handles on either side of a mixer tap usually turn in contra-directions relative to each other – clockwise and anticlockwise – to turn them on, because it seems more intuitive that both should appear to turn towards or away from yourself to produce the same effect. There are also different cultural conventions – for example, electric switches are flicked down for on in Europe, but up for on in the USA.

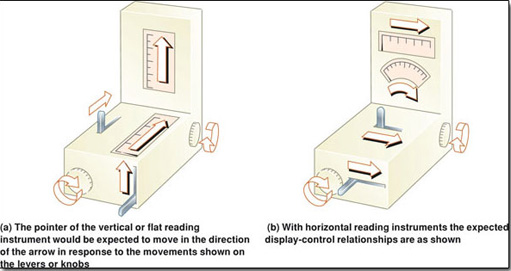

The arrangements in this example summarise the most common and unambiguous stereotypes for relations between controls and displays.

Stereotypes or conventions can be displaced by alternative learnt responses, but they frequently reassert themselves under conditions of stress such as tiredness or panic. Surveys have shown that many errors made by pilots interpreting aircraft instruments result from operating the controls in the wrong direction in response to a visual cue. In another typical example, a hydraulic press was wrecked by its operator. The press was operated by a lever that had to be moved down to raise the ram. One day, when an emergency occurred, the operator panicked and pulled the lever up to raise the ram. It, of course, came down.

The designers of the instrumentation on modern cars pay (or SHOULD pay) close attention to stereotypes, conventions, visibility, affordance and our expectations for feedback.