2 Innovation: adding value

The OECD/EC definition focuses on what is innovated – product, process, marketing or organisation – rather than how or why people or organisations choose to use an innovation, or how an innovation might be produced. Similarly, in the UK, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) defines innovation as: ‘The process by which new ideas are successfully exploited to create economic, social and environmental value.’ (BIS, 2011). Again, this definition draws our attention towards two fundamental features of innovation: that a new idea or invention is not by itself enough, and that it needs to be part of a wider process that realises value.

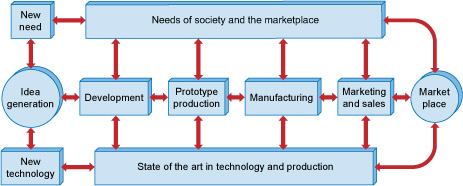

Figure 1 below illustrates this process as a series of activities progressing from ‘idea generation’ (loosely, invention) through to marketing and adoption in the market place (‘diffusion’). It is argued that this usually happens in the context of the ‘push’ of new technologies (‘state of the art in technology and production’) and the ‘pull’ of societal and economic demand (‘needs of society and the market place’).

Although this diagram is a rather stylised and simplified model of innovation (for example, it portrays innovation solely in relation to manufacturing, whereas service innovation represents a hugely significant arena), it does illustrate that innovation is a complex process and also serves to remind us that innovation happens in both technological and socioeconomic contexts, influencing them and being influenced by them. This brings us nicely to another important feature of innovation that also has a bearing in how we define it: how and why people and organisations decide whether or not to adopt an innovation. That is, how innovations spread or ‘diffuse’. As Rogers (2003, p.12) notes, from this perspective ‘An innovation is an idea, practice or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other object of adoption. It matters little, so far as human behaviour is concerned, whether or not an idea is ‘objectively’ new as measured by the lapse of time since its first use or discovery.’