3.5 Exercise

Exercise is well known for having multiple health benefits, for both physical and mental health. Despite this, finding time and motivation to exercise can sometimes be challenging. While finding time for exercise may remain elusive, recent research has shown that the gut microbiome may actually play a role in increasing motivation. Certain metabolites made by the gut microbiome can relay signals to the pleasure/reward centre of the brain via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. This improves motivation to exercise, as well as exercise performance, and may help to explain why there is variability between individuals around motivation and pleasure from exercise (Dohnalová, 2022).

Conversely, exercise can help to improve the health of the gut microbiome. Higher intensity or prolonged exercise improves cardiorespiratory fitness. This leads to improved oxygen intake and transport around the body in the bloodstream, including to the gut wall, which is beneficial to the health of the gut bacteria (Mailing, 2019). In fact, the distance runners regular undertake can correlate to the ratio between Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes!

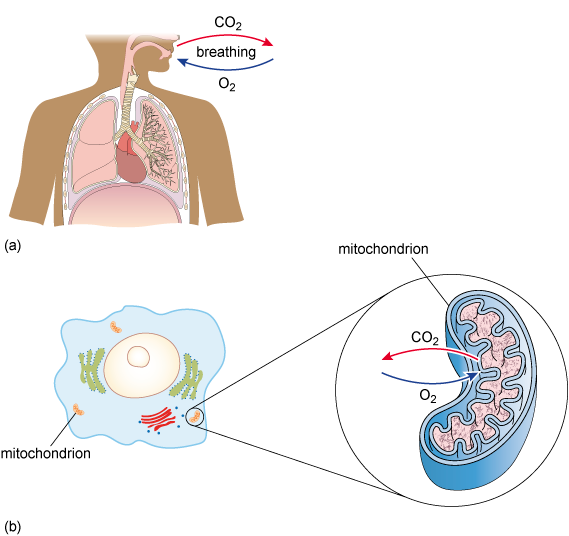

Recent research has shown that some elite endurance runners have an increase in a bacterial species called Veillonella. This species is thought to increase the amount of lactate that the athlete can tolerate, which in turn is linked to the function of mitochondria in the cells. Mitochondria are often called the ‘powerhouses of the cell’ as they produce the majority of the body’s energy (Figure 20). The metabolites produced by the microbiome, such as SCFAs, can improve the health and number of the mitochondria (Damman, 2024).

Lower intensity exercise helps to reduce transit time of the stool, that is, the stool passes through the GI tract faster. This reduces the amount of time pathogenic bacteria can come into contact with the gut wall and potentially displace the microorganisms of the microbiome. There is also an increase in SCFAs produced during low intensity exercise, which reduce the risk of colorectal cancer and Crohn’s disease. Exercise is also known to reduce the risk of both of these conditions (Monda, 2017).

However, exercise should not be considered in isolation. High intensity exercise combined with a diet high in UPFs has been linked to increased gut permeability and an increase in musculoskeletal injuries (Álvarez-Herms, 2023). This indicates that there is an important balance needed between a healthy diet and exercise, in order to maintain the optimal health of the gut microbiome.

Interestingly, the benefits of exercise on microbiome health are more pronounced during childhood, so it has been proposed that children who exercise more frequently will have a better microbiome diversity. This results in better brain development, more lean mass, and better energy regulation.