4.2 Irritable bowel syndrome and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

In contrast to IBD, the causes of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are currently poorly understood, but it is thought to be a collection of disorders rather than one single disease, all of which affect the functioning and motility of the GI tract. IBS is characterised by abdominal pain, change in stool consistency and stool frequency (diarrhoea or constipation). The different subtypes of IBS are based on stool consistency.

Historically, IBS was thought to be primarily due to altered gut motility and gut-brain interactions, which was triggered by psychological stressors. However, recent research has indicated that there are other factors involved in the development of the condition, including alterations in gut permeability, immune response and gut microbiome.

It is thought that dysbiosis leads to inflammation and increased permeability of the gut wall. Often this is triggered by an infectious episode of gastroenteritis, irrespective of the cause of the infection (e.g. bacterial, viral, or fungal). This infection then affects the stability and diversity of the microorganisms of the microbiome (Menees, 2018). However, the infection alone is unlikely to be enough of a triggering factor, and the individual may need to have other susceptibilities in order for IBS to develop.

Another potential risk factor that links dysbiosis of the gut microbiome and IBS is small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

-

Question 18

In which part of the GI tract are the majority of gut microbiome found?

-

The majority of the gut microbiome reside within the large intestine.

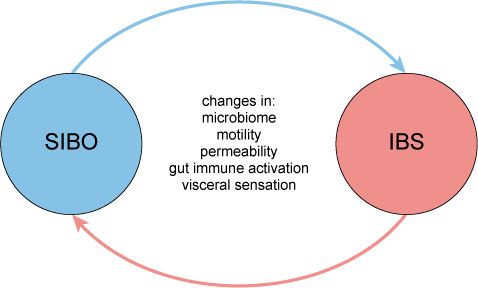

However, it is possible to get an overgrowth of the healthy bacterial groups from the microbiome or pathogenic bacteria (or a combination of both) in the small intestine. This leads to excessive usage of nutrients by the bacteria so fewer nutrients are absorbed into the human host. This is termed SIBO. SIBO can trigger an immune response, increase intestinal permeability, and alter carbohydrate digestion and absorption. All of these are similar to the effects of dysbiosis in IBS. In SIBO, the bacterial overgrowth often produces higher quantities of gas, causing bloating and flatulence, symptoms often described in IBS patients. This overlap of signs and symptoms suggests that SIBO may play an important role in IBS. However, it is currently unknown whether SIBO could be a cause of IBS or a consequence of the condition (Figure 26).

Several studies have reported promising results on the benefits of pre- and probiotics in improving the quality of life and reducing symptoms in IBS, but more work needs to be done to identify which substances and strains are most beneficial for which subtypes. You will learn more about pre- and probiotics in the final section.