4.1 Inflammatory bowel disease – Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

IBD is a group of two chronic inflammatory diseases which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC). These two immune conditions can be identified using diagnostic testing and imaging techniques. Genetics, environmental factors, and dysfunction of the individual’s immune system are important in the development of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

In addition, recent research has shown that many individuals with IBD have dysbiosis, which may be a key step in the early development of the disease. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiome leads to the colonisation of opportunistic harmful pathogens and increased permeability of the gut wall. This in turn triggers an immune response by the host, which can lead to extensive and damaging inflammation in the gut.

Inflammation in the gut wall in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can be seen using an endoscope. An endoscope is a long thin tube with a camera on the end, that is passed through the mouth or via the anus, to view the gut wall. Viewing of the upper GI tract is by gastroscopy, which enables observation of the stomach and first part of the duodenum. Viewing of the large intestine (colon), rectum and anus is via colonoscopy. In a healthy individual, the surface of the gut is smooth, and you can see the blood vessels. In IBD the gut wall becomes red, swollen, and raised in patches due to inflammation and ulceration.

While Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are both considered IBD, they differ in the severity, location and extent of the damage to the GI tract by the inflammation (Table 1)

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis |

|---|---|

| Inflammation and ulceration in any part of the GI tract, from the mouth to the anus. | Inflammation and ulceration only found in the large intestine, rectum and anus (colitis = inflammation of the colon). |

| Ulceration occurs in patches. | Ulceration tends to be continuous. |

| Inflammation penetrates and leads to destruction of the entire thickness of the gut wall. | Inflammation only affects the inner layer of cells lining of the gut wall. |

| Widespread damage to other abdominal organs and cavity can occur. | Damage localised to the GI tract. |

| Multiple other parts of the body outside of the GI tract can be affected, both within the abdominal cavity and other tissues/organs throughout the body. | Inflammation also affects other body parts, such as eyes, skin, liver and joints. |

Common signs and symptoms of both diseases are persistent diarrhoea, blood and mucus in faeces, abdominal pain and cramps, bloating and swelling, weight loss and extreme tiredness. Both conditions are often associated with poor digestion and absorption of nutrients, causing deficiencies that can affect other parts of the body. These deficiencies are normally dependent on the location and extent of the damage to the gut wall and tend to be worse in Crohn’s disease due to small intestine involvement, which is the main site of nutrient absorption.

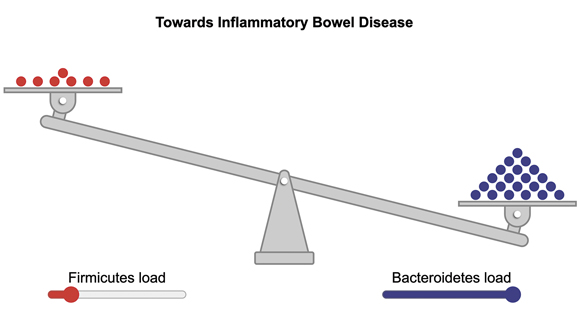

Both Crohn’s disease and UC have been linked with dysbiosis. You may recall from earlier that in a healthy gut microbiome, there is a balanced ratio of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes with typically slightly more Bacteroidetes than Firmicutes (although this varies by individual, age, and geographical region). However, in IBD there is often an increase in Bacteroidetes, which results in significantly more Bacteroidetes than Firmicutes. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio influences other microorganisms within the microbiome and is important for maintaining normal intestinal function and protecting against inflammation.

-

Question 17

What important molecule do Firmicutes produce in the gut microbiome? (Look back over Section 3 for a reminder.)

-

SCFAs, which protect against inflammation and help maintain the gut integrity.

There is currently no cure for either disease. However, treatments which modify the immune system to reduce inflammation and to alleviate the symptoms can be effective. Research into the benefits of taking probiotics in IBD are still very limited. A study by Stojanov, Berlec and Štrukelj (2020) suggests that orally administered, pharmaceutical-grade probiotics could help restore the F/B ratio in IBD by increasing the amount of Firmicutes and achieving a more balanced F/B ratio. While there is some early evidence to suggest that it may reduce inflammation and trigger remission (a reduction in disease pathology) in ulcerative colitis, to date there has been no evidence of a benefit in Crohn’s disease (Limketkai et al., 2022).