Faraday and Maxwell

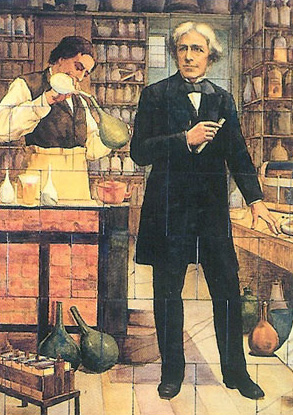

Michael Faraday (1791-1867)

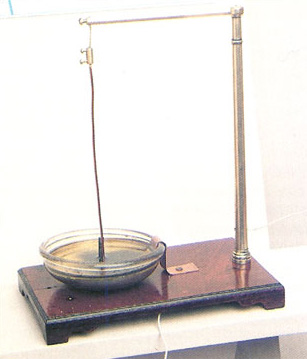

Michael Faraday was the son of a blacksmith. Apprenticed to a bookbinder at 14, he read about science, became enthralled with the subject, secured a job as a laboratory assistant at the Royal Institution in London, and eventually rose to be the Institution's Director and one of the most accomplished experimental researchers of all time. Amongst his many achievements, he is credited with the construction of the first electric motor and the discovery of both the principle and the method whereby a rotating magnet can be used to create an electric current in a coil of wire (still the basis of modern electricity generating plants). Faraday never became a very able mathematician, and it was his profoundly physical way of viewing the world that led him to create the concept of a field.

James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879)

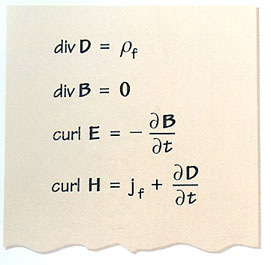

James Clerk Maxwell was the son of a Scottish laird. He studied at the Universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge and was appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at Aberdeen at the age of 27. Four years later he moved to King's College, London, where he spent his most productive period. In 1865 he resigned his post in London but continued to work privately on his family estate in Scotland. In 1871 he agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to become the first Professor of Experimental Physics in the University of Cambridge. He died, from cancer, at the early age of 47, but by that time he had already made fundamental contributions to the theory of gases, the study of heat and thermodynamics, and, above all, to electromagnetism. He recast the discoveries of Faraday and others in mathematical form, added an important principle of his own and thus produced what are usually referred to as Maxwell's equations - the fundamental laws of electromagnetism (Figure 24). Much of his work on field theory was published in his masterpiece, A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873).