1 Physics and the physical world

Studying physics will change you as a person. At least it should. In studying physics you will encounter some of the deepest and most far-reaching concepts that have ever entered human consciousness. Knowledge gathered over many centuries, that has been subjected to continuous scientific scrutiny, will be presented, along with its applications. Fact will follow fact, useful theory will succeed useful theory. Amidst this rich mix of information, newcomers to physics might not always appreciate how major discoveries have radically changed our attitude to ourselves, our natural environment, and our place in the Universe. In this course we have tried to avoid intellectual overload, to ensure that you have sufficient time to appreciate the significance of each of the main ideas and applications of physics discussed. We want your exposure to physics to change you, and we want you to be consciously aware of that change.

As part of that effort, this course gives a qualitative overview of some of the 'big ideas' of physics. Presenting ideas in this way, largely shorn of detail, and without much of the evidence that supports them, should help you to see the big picture and to appreciate some of the deep links that exist between different parts of physics. But this approach also has its dangers. It may obscure the fact that physics is more than a set of ideas about the world, more than a bunch of results: physics is also a process, a way of investigating the world based on experiment and observation. One of the biggest of all the 'big ideas' is that claims about the physical world must ultimately be tested by experiment and observation. Maintaining contact with the real world in this way is the guiding principle behind all scientific investigations, including those carried out by physicists.

Another important function of this course is to stress that physics is a cultural enterprise. All too often physics can have the appearance of being a collection of facts, theories, laws and techniques that have somehow emerged from nowhere. This, of course, is not the case. Throughout the ages, it has been the endeavour of individual men and women that has made possible the growth of science and the advancement of physics. This course attempts to emphasise the cultural aspect of physics by providing biographical information about some great physicists of the past. The coverage is neither fair nor complete, but it should remind you that physics is a human creation. Most physicists delight in tales of the struggles, foibles and achievements of their predecessors, and many feel that their understanding of physics is enhanced by knowing something of the paths (including the dead ends) that their intellectual forbears have trodden.

Do not expect to understand everything you read in this course. On the surface, we hope that it provides a coherent and interesting survey. But the more you think about some of the issues raised, the more puzzling they may seem. If, at the end of the course, you are left with questions as well as answers, that will be an excellent starting point for further studies in physics.

A note on powers of ten and significant figures

Physics involves many quantities that may be very large or very small. When discussing such quantities it is convenient to use powers of ten notation. According to this notation

The small superscript attached to the ten is called a power. As illustrated by the above examples, a positive power indicates the number of zeros after the 1; a negative power indicates the number of zeros before the 1, including the zero before the decimal point.

A quantity is said to be written in scientific notation when its value is written as a number between 1 and 10, multiplied by 10 raised to some power, multiplied by an appropriate unit. For example, the diameter of the Earth is about 12 760 kilometres; in scientific notation this could be written 1.276 × 104 km. One advantage of scientific notation is that it allows us to indicate the precision claimed for a given quantity. Stating that the Earth's diameter is 1.276 × 104 km really only claims that the diameter is somewhere between 12 755 kilometres and 12 765 kilometres. Had we been confident that the Earth's diameter was 12 760 kilometres, to the nearest kilometre, we should have written 1.2760 × 104 km. The meaningful digits in a number are called significant figures. (Significant figures do not include any zeros to the left of the first non-zero digit, so 0.0025 has two significant figures, for example.) One advantage of writing numerical values in scientific notation is, therefore, that all the digits in the number that multiplies the power of ten are significant figures.

We will introduce the units in which physical quantities are generally measured. For example, time is measured in seconds, length in metres, energy in joules and electric current in amperes. A detailed understanding of these units is not needed yet, and would make a rather dull start to this course. In the few places where units appear, please skip past them if the meaning is unclear.

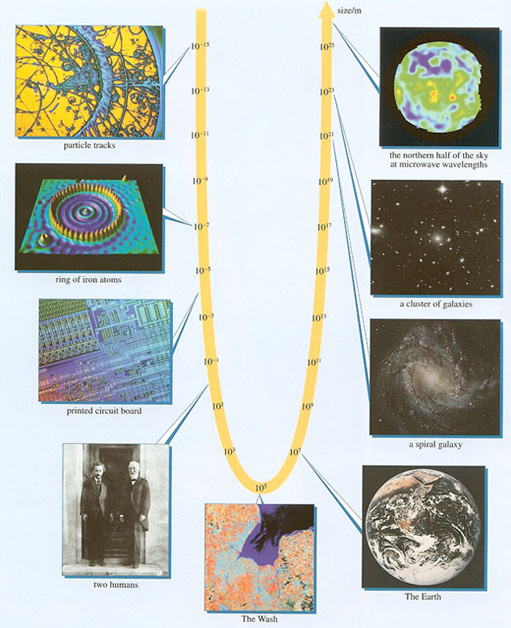

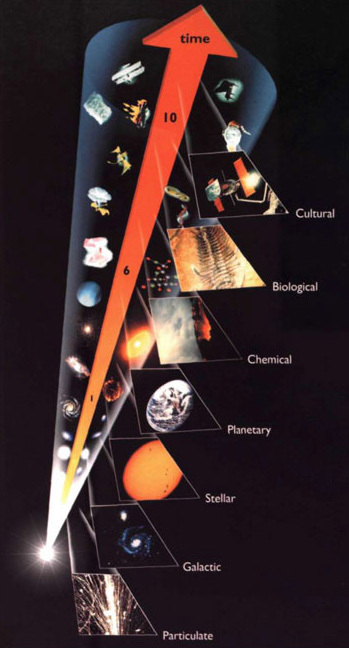

Many physical quantities span vast ranges of magnitude. Figures 1 and 2 use images to indicate the range of lengths and times that are of importance in physics.