1 Overview

1 The importance of evidence

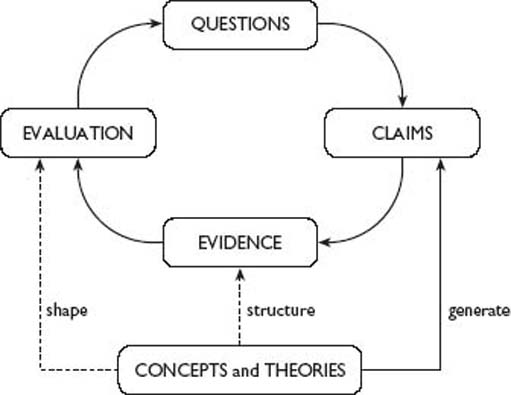

The gathering, presentation and assessment of evidence are crucial and indeed inescapable parts of the practice of social science, hence the crucial role of evidence in the circuit of knowledge (see Figure 1).

Social science and the circuit of knowledge – Box 1

We need to think about the practical nuts and bolts of constructing an argument:

-

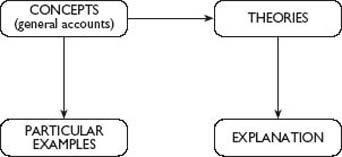

Clearly defined general concepts help us organise and think about particular examples of a phenomenon.

-

Concepts can be combined together to generate theories which are general frameworks for providing explanations of phenomena.

But how do we begin to examine and evaluate the quality of those concepts, theories and explanations?

From a discussion of this question it follows that:

-

Social science enquiry starts with questions.

-

Evaluating answers to these questions requires us to sharpen up our argument. We need to generate specific claims, descriptive or explanatory, that are fit for rigorous exploration.

-

Social scientists reach for evidence when examining these kinds of claims.

-

Evidence does not speak for itself – but must be carefully handled, siftedand interpreted.

-

This process is broadly what we call evaluation – a process which often generates new questions to be resolved as well as confirming or contradicting the original claims.

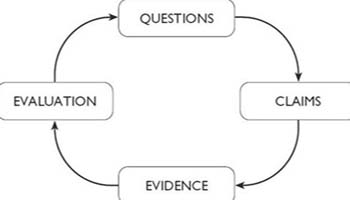

In this course we have linked these processes of enquiry together in what we call the circuit of knowledge, see Figure 2(a).

You will find later in the course how concepts, theories and the arguments one can construct out of them also shape the way we use evidence and do our evaluation. But for the moment just think about concepts and theories as a way of generating descriptive and explanatory claims, see Figure 2b).

Let us see how the circuit works in a bit more detail.

Questions

Consider three questions.

-

How are identities formed?

-

How much control do we have in shaping our own identities?

-

Are there particular uncertainties about identity in the contemporary UK?

In order to begin answering these questions it is necessary to focus on more specific and manageable claims, that is areas of identity which might be particularly important. Here we will focus on issues of work and work-based identities.

So we can rephrase our questions as:

-

How are work-based identities formed?

-

How much control do we have over work-based identities?

-

Are there uncertainties about work-based identities in the contemporary UK?

What are the claims made in response to these questions and how do concepts and theories of identities help us generate those claims?

Claims

Drawing specifically on the arguments of Mead, Goffman and the accounts of social structures, we picked out these claims.

-

Work-based identities are formed by the interaction of individuals with economic structures which generate a repertoire of roles, symbols and conventions that individuals take up and identify with.

Individual control over work-based identities are structured, patterned and constrained by the pre-existing conditions of work and distribution of economic opportunity.

-

Individuals may have more choice over whether they choose to identify with work-based identities than other identities such as gender or place.

-

For men who have worked in traditional industrial sectors, work-based identities have become more uncertain.

Evidence

The next step involves looking for some information against which these kinds of claims can be tested.

John Greaves's autobiographical account offers one type of evidence about the importance of work and identity. This piece suggests that structural changes in the economy can have significant impacts upon identities. [Please read the autobiography by clicking on the “View document” link below.]

Click to view the John Greaves extract [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Activity 1

-

What does John Greaves's writing tell us about how identities are formed?

-

How much control did he have in shaping his work-based identity?

-

Does his account suggest that there is greater uncertainty about work identities in the late 1990s?

Discussion

-

John's account suggests that paid work, especially in work like coal mining, is a very important dimension of identity. Miners lived in a community dominated socially and economically by the coal industry. There is a strong connection between personal experience and the social factors related to paid work, and a strong sense of belonging – of being the same as others within the community.

-

Within coal mining communities there was little room for the expression of alternative identities to work-based ones – for men at any rate, so all-encompassing was the place of coal mining in the life of the community. External social forces that brought about the collapse of the mining industry clearly had, and still have, significant impact on the identity of John and those who live in his community.

-

This account does suggest there are greater uncertainties about identity, especially work-based identities in the coal industry (and other heavy manufacturing industries) in the UK. This is illustrated by the irony of the old Coal Board slogan ‘A Job for Life’. For many people like John, who had expected that to be the case, they were left not only without a particular job, but without any job, in a community which had been prosperous and was, by the late 1990s, impoverished.

Social science and the circuit of knowledge – Box 2

The activity above begins to explore the relationships between asking questions and making claims and using evidence. However, you are probably already thinking of some more questions which we could be asking about our example of the link between work and identity. In particular, one person's account might not be representative of the UK as a whole, or even coal miners in general. We need more quantitative evidence; especially to address the question about greater uncertainty in relation to changing social structures.

The evidence we have looked at so far is qualitative and provides significant insights into the personal side of the identity equation. It takes on board personal feelings as well as conveying the sense of community at two different moments in time, but it would be useful to know more about the scale of pit closures and of alternative employment which might have become available, for example. Is this story only about men? The community John describes is one peopled by women, men and children. What might be missing from this account?

Evaluation

How far have we gone around the circuit of knowledge? We started by focusing our general framing questions into more specific work-identity related questions. We drew on theories of identity to generate specific, sharper claims and looked at one piece of autobiographical evidence.

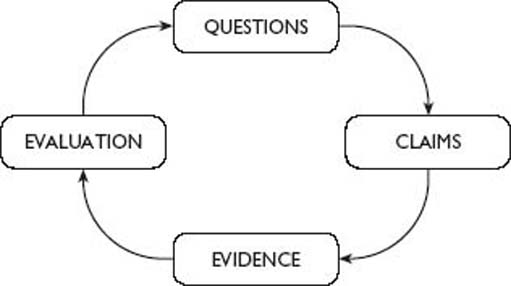

However, as we evaluate the original claim, in the light of evidence available to us, we might need to consider some more questions. What else do we need to know? What would more quantitative evidence about economic change and employment add? John Greaves's story is an account of a changing work-based identity but it is also a gendered account. It would also be interesting and useful to find out about the experiences of women in the community and whether a changing work identity had an impact on gender identity too. By comparing the work, paid and unpaid, and home experiences of women and men we might come up with a different set of claims about identity. We started with questions and the investigation has led to the addition of more questions as we complete our circuit of knowledge (see Figure 3).

It is a respect for evidence which allows us as social scientists to be satisfied that our claims about society make more than common sense. When faced with the descriptive claim that ‘Nobody needed to lock their doors in the 1950s’, or the explanatory claim that ‘It's the permissive 1960s that we have to blame for all this crime’, we can simply agree with the claim, or we can deny it just because we feel like it or on the limited basis only of personal experience. As social scientists, though, we should ask, ‘How do you know that?’ and begin to explore the evidence which would either confirm or deny the claim. Of course, we need to be able to understand the evidence to be able to make use of it, so, in this course, we want to help you get the most out of various forms of numerical and textual evidence.

Before we do that it's worth noting that there is a distinction to be made between quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Quantitative evidence is concerned with the quantity of things; for example, how many crimes are committed and how often. Quantitative evidence tends to be about numbers, percentages and statistics and is often presented in the form of graphs and tables.

Qualitative evidence is about the quality of things, like what it feels like to be a victim of crime. Qualitative evidence is usually concerned with words and images and is presented in the form of reports, analysis of interviews, autobiographical accounts, or documentary photographs. Qualitative researchers often focus on everyday life itself.

Neither of these forms of evidence is better or more useful than the other, indeed they often complement one another, but they need to be used appropriately in terms of the question being asked and the claim being made.

So let's look now at both quantitative and qualitative evidence in turn, demonstrating how each can be read and understood.