Unit 4: Report and respond

4.2 Barriers to reporting

© Serhii Radachynskyi / 123RF

In Course 1: Introduction to Safeguarding in the International Aid Sector we explored barriers to reporting and how societal perceptions, myths and assumptions, and stigma and shame play a big part in preventing survivors of SEAH from reporting.

It is not uncommon for survivors to be blamed for suffering harm from SEAH.

For example, they may be accused of not taking appropriate precautions, exposing themselves to danger, or dressing in ways that encourages or invites SEAH. Where victim-blaming is prevalent, people may be more reluctant to report. Survivors may also internalise blame and feel that they do not deserve help or support.

© Ponomariova_Maria / iStock / Getty Images Plus

There are also negative consequences of reporting. Sometimes survivors may not want to report for fear that they would not be believed, particularly if the perpetrator is in a more powerful position or enjoys the support of leadership/management.

They may also worry that reporting may result in aid to their community being stopped, or that reporting will damage their chances of getting married in the future. The fear that the perpetrator would lose their job leading to impoverishment of their family may also deter reporting.

Other factors inhibiting reporting include fear of retaliation (by the perpetrator, families, employers or society) and limited trust in internal or external reporting systems.

|

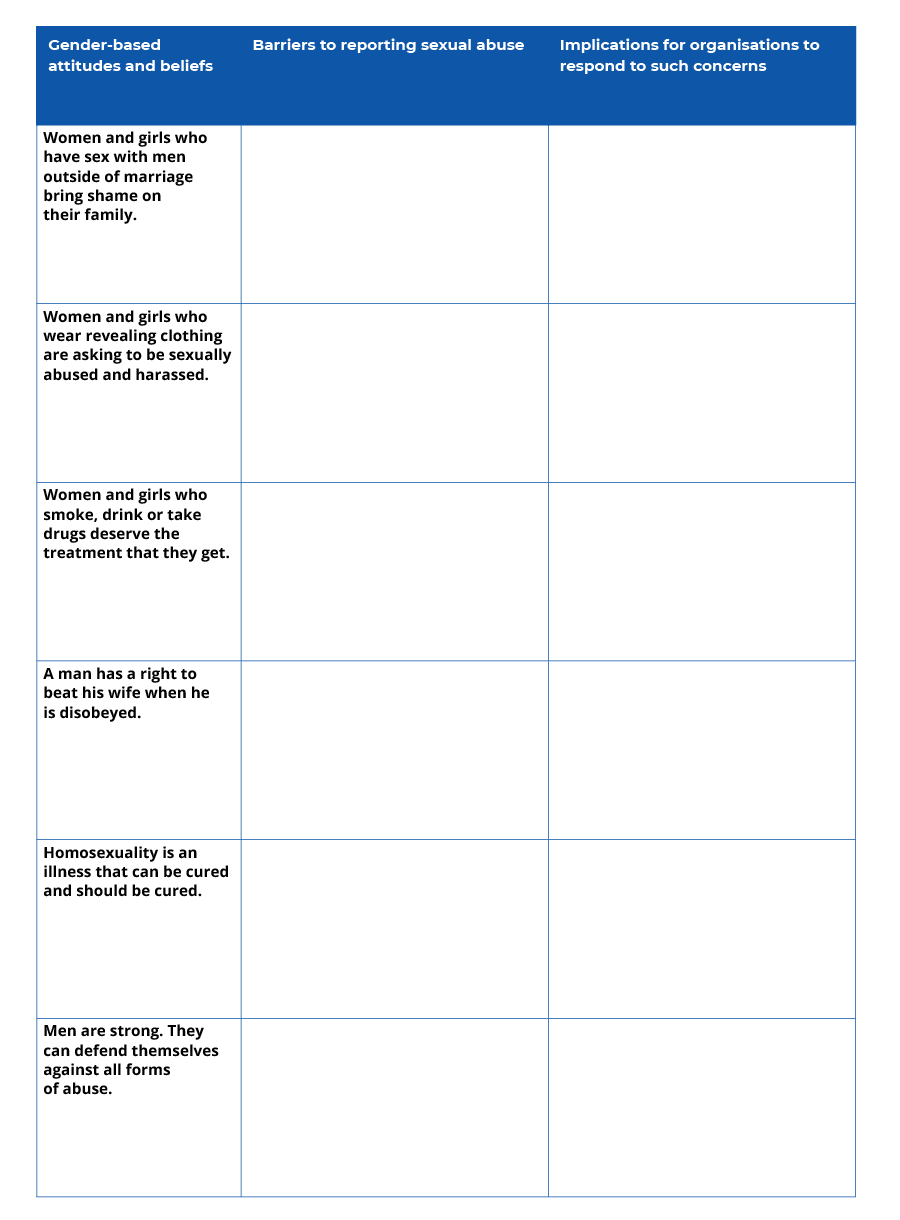

Activity 4.1 Discriminatory attitudes and beliefs Here we explore some of the barriers to reporting which naturally impact on the effectiveness of implementing organisational safeguarding measures. The table below shows a list of discriminatory gender attitudes and beliefs that it is not uncommon to encounter in different parts of the world. What do you think the implications of these beliefs might be for reporting safeguarding concerns in the context of organisational work or programming? Use the table below on discriminatory gender attitudes and beliefs and fill in the two missing columns. Here is a writable version of the template shown below. You can type into this PDF form and then save it and/or print it.

Here is a version of the template with some ideas in each of the columns to compare with your own. |

Barriers to reporting for men and boys

© stock_colors / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Whilst it is important to provide support and services, such as safe spaces, counselling services and medical care, specifically for women and children, it is equally important to make sure men, boys and people of non-binary genders (LBGTQI – lesbian, bisexual, gay, transgender, queer (or questioning) and intersex) are not overlooked and that their specific needs are catered for.

Disclosure of SEAH by men and boys may be perceived by society as a sign of weakness. They may fear shame, ridicule, further harm or not being believed and avoid reporting it.

|

Activity 4.2 Men, boys and sexual violence Read this article from the Refugee Law Project (2020) in Uganda, about an NGO that works with men and boys affected by sexual violence. It outlines some of the barriers to reporting and the experience of working with male survivors. In your learning journal reflect on some of the ways organisations could support men and boys to disclose safely and how they might respond. |

Barriers to reporting for LBGTQI people

© ljubaphoto / iStock / Getty Images Plus

In many contexts, heterosexual relationships are considered the norm, with other kinds of relationship considered something ‘deviant’ or ‘unnatural’ to be treated or cured.

These kinds of views might not only deter survivors of same-sex abuse from reporting concerns, but also influence ideas about what kind of ‘support’ is available or appropriate.

Due to phobias and stigmas associated with being non-heterosexual, LGBTQI survivors of sexual violence face specific challenges when attempting to access support services.

Barriers faced by LGBTQI people in accessing help or support can be complex and include:

- Structural: Protection services for LGBTQI people are non-existent because their sexuality is illegal in many countries.

- Cultural: Services which may be available are not designed or delivered to be accessible to or inclusive of LGBTQI people.

- Individual: LGBTQI people’s perception of the support system, of their selves, of the abuse, and of their relationship with the perpetrator/s.

|

Activity 4.3 Sayed – A case Study Read this case study about Sayed, who is an expatriate staff member working for an international agency. Sayed is an expatriate staff member working for an international agency in Country X. This international agency works on SGBV programming focused on supporting women and girls. Sayed has a relationship with Jack, a male colleague from another organisation. Initially the relationship was very pleasant, however Jack started getting jealous, controlling and abusive. Jack threatens to inform Sayed’s family about his sexuality and Sayed fears deportation back to his home country where those like him will be imprisoned and probably tortured. Sayed contacts a local domestic violence service, which refuses to offer him support saying they don’t provide support to male victims. One evening Sayed could not stand it any longer: he calls Jack’s employer to complain following a physical attack by Jack. The employer feels very uncomfortable with this disclosure and does not want to intervene. The employer warns Sayed that he should not make up stories and waste organisational time. (© Adapted from Barriers faced by LGBT+ people in accessing non-LGBT+ domestic abuse support services) Having read the short case study, consider these two questions noting your responses in your learning journal:

|