10.2.1 Rural water supply approaches

To address the low access to water supply in rural areas the Water Resources Management Policy (MoWR, 1999) supported decentralised management, and integrated and participatory approaches to providing improved water supply services. As you have read, this policy was part of the background to the OWNP which also encourages decentralisation of management and the involvement of different stakeholders, including NGOs and communities. The recovery of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs is also recognised and supported by this policy.

What makes the Water Resources Management Policy and OWNP similar?

Both documents support decentralised management, integration and the participatory approach of both stakeholders and the wider community.

In Study Session 6, you read that the OWNP’s rural water supply activities include various studies; constructing new point sources or small piped schemes with distribution systems, including multi-village schemes where appropriate; the rehabilitation of existing point sources and expanding small piped schemes. You were also introduced to the different approaches or modalities to implement and manage these activities. We will now describe these in a little more detail.

Woreda-managed project

The woreda-managed project (WMP) is a rural WASH implementation modality in which the Woreda WASH Team (WWT) takes the lead. They are responsible for administering funds allocated to woreda, kebele or the community for capital expenditure on water supply and sanitation activities. Although the kebele administration and WASHCOs are involved in project planning, implementation, monitoring and commissioning the project, the WWT is effectively the Project Manager and is responsible for contracting, procurement, inspection, quality control and handover to the community. Typically a WMP approach is used for small schemes such as spring development, hand pumps, and the software component of sanitation. (Software components are any activities that focus on knowledge, attitude and behavioural changes of the individual or the whole community. Hardware components are the physical parts of a scheme such as well linings, pumps, latrine slabs, lavatory pans, construction materials etc.)

The construction of WMP schemes is supervised by woreda staff and projects are transferred to the community after the design and implementation stages are completed by the woreda. This has traditionally resulted in very low community participation and ownership.

Community-managed project

The community-managed project (CMP) is a rural WASH implementation approach where communities are supported to undertake all stages of a project, from initiation through planning to implementation and management continuing into the future. These projects use funds that are transferred to, and managed by, the community. The major features of the CMP approach are:

- Fund Transfer: Funds for physical construction are transferred to the communities from woredas or through intermediaries selected by the communities, thus making communities responsible during the full project cycle from planning and implementation (including procurement of most materials and labour) to O&M.

- Community Project Management: The communities, through water and sanitation committees (WASHCOs), are responsible for the full development process through planning, financial management, implementation and maintenance. The communities contribute a minimum of 15% in cash or in kind (usually labour). WASHCOs manage not only community-generated funds, but also the government subsidy provided for capital expenditures.

- Procurement: A further aspect of community management is that the WASHCO is directly responsible for procuring (buying) the goods and services required for water scheme construction and installation.

The CMP mechanism is intended mainly for low-level technologies such as hand-dug wells and spring protection. An example of a community-managed project is the Debero-Garmojo water point (Figure 10.1). Debero-Garmojo is in the Abichugena woreda, Oromia region. The water point was constructed by local community with the support of the woreda administration and the government of Finland. The water comes from a spring and is piped into a collection tank which has three taps and serves 30 households. The WASHCO was responsible for its planning, procurement, contracting, management, and operation and maintenance.

NGO-managed project

As you know by now, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are important stakeholders in the OWNP as donors, implementers and knowledge disseminators. Their funding and management arrangements vary considerably but, combined with national WASH principles and practices, they foster community initiatives, develop community leadership and require community investment in water supply projects. In some cases, NGOs administer external resources on behalf of the community. In others, they make external resources available to the community directly or through microfinance institutions to support construction and management.

NGOs have flexibility and are able to increase community involvement, ownership and accountability. NGO-supported projects follow procedures agreed between the NGO, its partners, the Ethiopian government and the region or woreda where the activities are located. They should comply with policies on cost-sharing, community contributions, reporting and monitoring indicators. NGOs are included in resource mapping at all levels and will be requested to provide information for preparing consolidated annual WASH plans and budgets. (Resource mapping is the identification of the sources and amounts of all possible funds for a project.) NGOs will also be requested to provide periodic progress reports on their projects to WASH Coordinators at various levels.

You have already seen several examples of NGO-managed projects in this Module. As discussed in Box 9.1 in the previous study session, the term NGO may be used loosely, and in this context is frequently applied to projects managed by organisations like UNICEF and the World Health Organization (Figure 10.2), which are not NGOs in the strict sense of the term.

Self-supply

Self-supply was defined in Study Session 6 as the construction and use of small-scale water schemes at household level, such as hand-dug wells. As stated in the manual prepared by Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE, 2014a) self-supply means ‘improvement to water supplies developed largely or wholly through user investment by households or small groups of households’. Self-supply involves households taking the lead in their own development and investing in the construction, upgrading and maintenance of their own water sources, water-lifting and treatment devices and storage facilities.

Multi-village water supply schemes

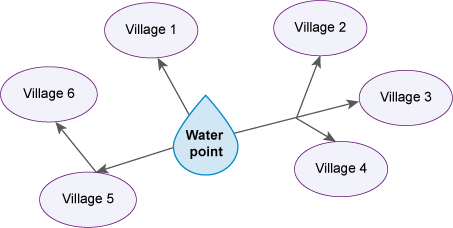

As the name suggests, these are schemes designed to provide water to several villages from a single source (Figure 10.3).

Regions and zones are mainly responsible for this type of scheme and they undertake all the studies, design, management, construction and supervision. These schemes are more complicated and construction requires higher-level technology to serve larger populations of up to 100,000 people in the combined villages. Multi-village water supply schemes will be supported under certain conditions, provided that feasibility studies verify that the proposed sources are adequate and that the schemes can be socially, technically and financially sustainable.

10.2 Rural WASH implementation approaches