10.2.2 Rural sanitation and hygiene promotion

Currently there are a number of different approaches to promoting rural community sanitation and hygiene in Ethiopia. We will highlight two of the most important: community-led total sanitation and hygiene, and sanitation marketing.

Community-led total sanitation and hygiene

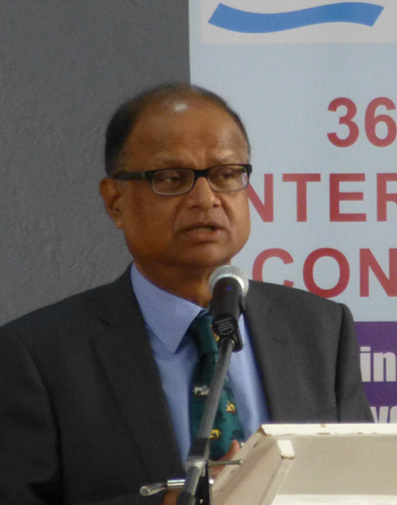

Community-led total sanitation (CLTS) is an approach which emphasises changing the behaviour of all people in a community in order to stop open defecation and encourage good hygiene practices in and around the home. CLTS was introduced in Ethiopia following a hands-on workshop in October 2006, organised by Vita, an Irish international development agency working in the Horn of Africa, and led by Dr. Kamal Kar (Figure 10.4). The Federal Ministry of Health had taken the initiative to use this approach as the main tool to improve rural sanitation by training Health Extension Workers (HEWs) in the technique. Since that time, the approach has been developed and renamed in Ethiopia to explicitly include hygiene and is now known as community-led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH).

The aim of CLTSH is to achieve open defecation free (ODF) status. This is awarded to villages and communities when they have achieved the situation whereby everyone has access to a latrine and no one defecates in the open at any time. The award of ODF status is cause for great celebration in the community (Figure 10.5). ODF status is achieved through a process of social awakening stimulated by facilitators from within or outside the community. The approach concentrates on the behaviour of the community as a whole rather than on individuals.

The CLTSH process involves trained facilitators working with communities to inspire and empower them to stop open defecation and to build and use latrines for themselves. The facilitators encourage people to take responsibility and consider their own behaviour rather than rely on external subsidies to buy hardware such as latrine slabs. Community members come together with the facilitators in group discussions to analyse the extent of open defecation in and around the village (Figure 10.6). They consider the implications of this for faecal-oral contamination and the resulting detrimental impact on human health that could affect every one of them.

The CLTSH approach works by creating a sense of disgust and shame among the community in a stage in the process called triggering or igniting. The process brings them collectively to the realisation that they quite literally will be eating one another’s ‘shit’ if open defecation continues. When they realise this shocking fact, the people become very enthusiastic about taking action to improve the sanitation situation in the community (Kar, 2005).

Sanitation marketing

Since the introduction of CLTSH, significant numbers of households have gained access to self-constructed basic latrines. However, many self-constructed latrines fall short of fulfilling the minimum standard of improved sanitation and hygiene facilities, as shown in Figure 10.7. This is one of the reasons for introducing sanitation marketing.

Why is the latrine shown in Figure 10.7 inadequate?

The pit is covered with logs rather than a slab. This will not provide separation between the people using the latrine and their waste. It is unstable and difficult to find a secure footing and is likely to break and collapse while someone is using it. Also there is no proper infrastructure around the pit to provide privacy.

Sanitation marketing is a relatively new approach to improving sanitation provision and does not have a single precise definition. The Water and Sanitation Program’s Introductory Guide to Sanitation Marketing explains that ‘some practitioners define sanitation marketing as strengthening supply by building capacity of the local private sector; others discuss it in terms of “selling sanitation” by using commercial marketing techniques to motivate households to build toilets’ (Devine and Kullman, 2012).

In Ethiopia, the National Sanitation Marketing Guideline defines sanitation marketing as ‘satisfying improved sanitation requirements (both demand and supply) through social and commercial marketing process as opposed to a welfare package’ (MoH, 2013). The national guideline sets out three pillars for the approach which are:

- Strengthening an enabling environment for sanitation marketing programme.

- Creating access for improved sanitation technology options.

- Generating demand for improved sanitation technology options (MoH, 2013).

In practice this approach includes a range of different activities that encourage people to build latrines and adopt good hygiene behaviour and also to create business and commercial opportunities. An important feature is that new sanitation services are not provided for free. Figure 10.8 shows an example of a sanitation marketing enterprise where latrine slabs are constructed for sale.

10.2.1 Rural water supply approaches