Boundary objects

Introduction

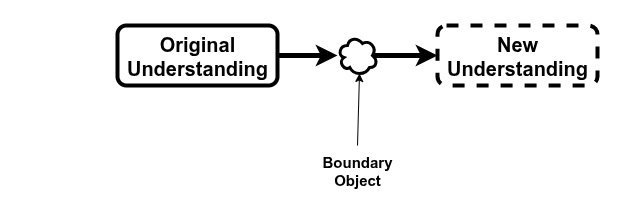

One of the problems facing the development of good group communication (either in groups of many people or just two people) is understanding what other team members mean when they use a phrase or concept. These misunderstandings can cause individual and group confusion and lead to friction and poor team performance. The literature suggests that if individuals in a group can gain an understanding of boundary objects, they can use this understanding to improve group communication (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Kynigos and Daskolia, 2021; Star and Griesemer, 1989;Suchman, 1993). As reflection is similar to an individual having a conversation with themselves an understanding of boundary objects is also important for an individual's reflection.

What is a boundary object?

Star and Griesemer (1989) define boundary objects as:

"objects which are both plastic (flexible) enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. They are weakly structured in common use, and become strongly structured in individual-site use. They may be abstract or concrete. They have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable, (being) a means of translation. The creation and management of boundary objects is key in developing and maintaining coherence across intersecting social worlds."

They are things that allow us to move beyond individual people, things or concepts (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011). They act as a bridging mechanism in understanding between people or disciplines being ‘both-and’ i.e. they belong to each individual area and to both of them together. They are also ‘neither-nor’ i.e. they do not fully belong to either area.

Star (1989) suggests that boundary objects may be artefacts of some sort (e.g. objects, models, written documents, tools, processes) that help with team building and crossing boundaries. She also describes them as objects that are shared and shareable across different problem solving contexts and that they work to establish a context that is common to all members of team. Matsumoto et al. (2022) add to Star's list of artefacts the use of vocabulary and concepts that connect people across physical, academic, and relational boundaries with Carlile (2002) adding numbers, blueprints, tools, and machines.

Akkerman and Bakker (2011) feel that boundary objects provide only partial information so that they can be understood by all participants. On the other hand for boundary objects to be effective they need to be rich enough to capture multiple meanings and perspectives so that participants can relate to them from their own perspectives.

Boundary objects fail if they do not capture multiple meanings and perspectives and if they are not rich enough or provide only partial communication (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011). They may be perceived differently over time and may lose their function (Barrett and Oborn, 2010). Carlile (2002) points out that not every object works as a boundary object and that an object that works in one setting can become a block in another.

Why are they useful?

Boundary objects are useful because individuals tend to act within their own boundaries. These boundaries will influence their interactions, relationships, meanings and what they reflect upon. The different backgrounds of individuals may create difficulties in their communication and their interactions but can also create opportunities for learning, communication and collaboration (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011). These difficulties can be mitigated by developing boundary objects within the team (Kynigos and Daskolia, 2021); a boundary object makes a concept more explicit so that it can be communicated across technical and conceptual gaps (Fischer, 2004). Carlile (2002) observes that knowledge is both a source of and a barrier to innovation, the nature of the knowledge that drives innovative problem solving within a domain actually makes it more difficult to problem solve and create knowledge across domains. Fischer et al. (2005) feel that boundary objects: remind people of knowledge rather than storing it; act as conversation pieces that ground shared knowledge; evolve and become more meaningful and understandable, this being achieved by using them, discussing them and refining them.

They may be perceived differently over time and may lose their function (Barrett and Oborn, 2010). Bruner (1996) stresses the importance of externalisation of ideas to help us make new associations and because they lessen our cognitive load. Boundary objects help people transition and have interactions between areas (either physical or conceptual) (Suchman, 1993). A boundary object helps provide continuity across areas helping to facilitate interactions and practices. Lamott and Molnar (2002) suggest that boundary objects can help with a fine grain appreciation of diversity. Words and concepts mean different things to different people and although this can cause problems with communication Wertsch and Toma (1995) see this as an opportunity for opening up ‘thought spaces’ with McGreavy et al. (2013) thinking that good communication is central to boundary work.

Carlile (2002) identifies three characteristics of boundary objects: they create a shared syntax or language so that individuals can represent their knowledge to each other; they provide a concrete way for individuals to specify and learn about their differences; and they facilitate individuals in jointly transforming their knowledge.

Examples

As an example Arias et al. (2000) used physical blocks as boundary objects in an urban planning exercise to represent various elements of the urban planning problem being addressed. A block may have represented a bus. Participants then interacted with the block by moving it around a map. This helped them discuss what they understood by a bus; brought into the open different views; helped them come to a common understanding; and opened up other possibilities in the problem they were considering. This is an example of how a boundary object can externalise a concept.

Another example of a boundary object might be the word 'model'. An architect might think of this as a physical thing whereas a mathematician might think of it as a set of equations.

A third example might be an electron. It may be understood by an electrical engineer as something that carries current whilst a chemist might be thinking of it as something that creates chemical bonds between molecules.

Summary

To summarise, boundary objects can be almost anything as long as they can act as a bridging mechanism for people from diverse backgrounds. They help people resolve misunderstandings and come to a common understanding of key areas so leading to more effective working relationships. When a group identify and bring into the open a boundary object it may cause considerable discussion including heated arguments. This is crucially important as the purpose of discussion is to come to a common understanding about important areas. So although coming to an agreed understanding about boundary objects can be cognitively painful it is important that participants perceive them as part of a learning process.

Practice

Thinking back to the Practice you did yesterday can you identify any boundary objects that might have helped these people to understand each other better?

How might you explain these boundaries objects to the people involved?