2.8 Christ’s portrait

In 1590 one of Raphael’s biographers, Giovanpaolo Lomazzo, wrote that ‘his face resembled the one that all the greatest painters use to represent Our Lord’ (Shearman, 2003, vol. 2, p. 1367). What the face of Christ looked like was, in Raphael’s lifetime, a matter of particular interest. In the last decade of the fifteenth century, two books printed in Germany publicised what was claimed to be a recently discovered letter by Publius Lentulus, a purported Governor of Judea during the time of Jesus. The ‘Lentulus letter’ caused a sensation, not least among artists, because it seemed to give a very detailed description of Christ’s appearance. It reads:

His hair is of the colour of the ripe hazel-nut, straight down to the ears, but below the ears wavy and curled, with a bluish and bright reflection, flowing over his shoulders. It is parted in two on the top of the head … His beard is abundant, of the colour of his hair, not long, but divided at the chin. His aspect is simple and mature, his eyes are changeable and bright … He is the most beautiful among the children of men.

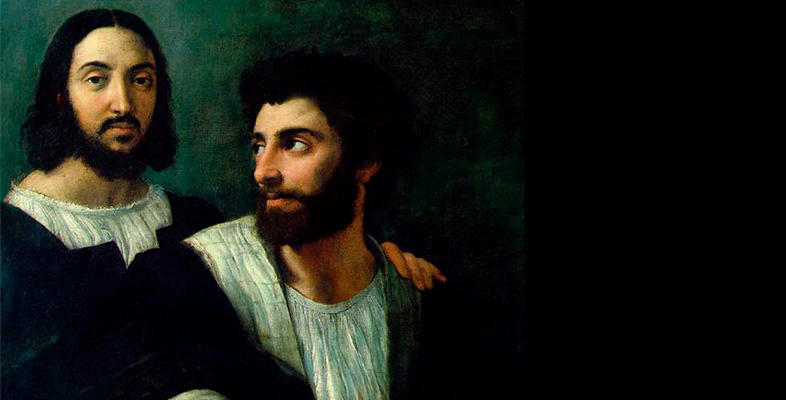

It was this image, the ‘Holy Face’ of Christ, that Raphael would use as a model for his own ‘divine’ face in a Self-portrait with a Friend in the Louvre, a portrait we will explore in Section 2.9. What you should take note of now is interest in the Lentulus letter among fifteenth- and sixteenth-century artists, the physical type described in the letter, as well as the long-standing visual conventions for the depiction of Christ that the Lentulus letter draws upon, in particular that of the ‘Holy Face’: this is the image thought to have been miraculously imprinted on a veil which St Veronica had given to Christ on his way to the crucifixion. Wiping the sweat from his face, it was believed, Christ left his own portrait on Veronica’s veil. This cloth, with the ‘authentic’ portrait of Christ it preserved, was kept by the popes in Rome as one of the holiest relics in Christendom. Not only was this image a relic of Christ’s physical presence on earth; it was also an ‘acheiropoieton’, an image made ‘without human hands’. Veronica and her veil are visualised in Hans Memling’s Saint Veronica (c.1470–75) (Figure 5).

Raphael, and the German master Albrecht Dürer, contemporaries who were both keenly interested in cultivating their identities as ‘divine’ artists, would both show themselves as Christ-like figures in their self-portraits, with features that allude directly to the miraculous Holy Face of Christ. Dürer’s famous self-portrait in Munich (Figure 6) is formatted like an icon, his pose, hairstyle and beard imitating those of Christ. The date and monogram that appear on the left-hand side of the work, ‘1500 AD’, underscore the direct parallel between Christ and the artist, since AD stands here for ‘anno domini’ as well as ‘Albrecht Dürer’. It is no coincidence that a cult of genius that developed around Dürer, like Raphael, focused on the artist’s physical beauty and Christ-like appearance as a sign of his divine favour.