1 Introduction to fingerprints

In this section you will learn the principles used in classifying and matching fingerprints (often called 'marks').

Question 1

From your general knowledge, do you know what is special about fingerprints that makes them so useful to forensic science?

Answer

The skin on the ends of human fingers has ridges which form patterns that are unique to an individual.

Question 2

What do forensic scientists mean by 'individualisation'?

Answer

Individualisation is the process of unambiguously connecting a single individual or object to a crime scene.

The use of fingerprints in the identification of criminals is the most frequently applied technique in forensic science. As the main method of establishing identity from traces left at crime scenes, fingerprint matching is currently presented in court in the UK five times more often than is DNA matching. You will learn that fingerprint evidence is usually very sound and is one of the most reliable forms of identification, though there are challenges to its use and human errors can be made. However, these problems and errors do need to be put in the context of the outstanding history of success in using fingerprints in individualisation.

Perhaps the earliest recorded examples of what might today be cited as the forerunners of forensic science appeared in ancient China and Assyria. Thousands of years ago the Chinese and Assyrian people used fingerprints to establish the identity of clay artefacts, and later on documents, by labelling them with a unique and identifiable mark - the finger (or thumb) print.

The Chinese also used thumbprints on legal documents and on criminal confessions. As far as is known this was a simple and informal classification of the fingerprints, rather like a signature. But it is perhaps the first sign of recognition that a person's fingerprints are unique to that person - something that is still considered to be true today and forms one of the foundations of individual identification. The process of 'matching' individuals and things to a crime scene that grew from fingerprint analysis is still the basis of much of forensic science.

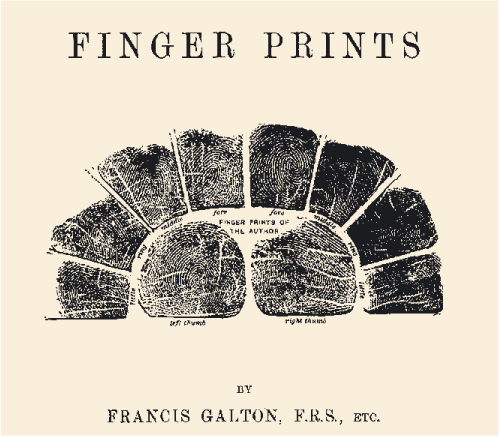

Systems for the classification of fingerprints had been developed during the 19th century by several investigators. The discovery that most fingerprints were invisible to the naked eye but could be made visible by the use of powders was also developed during the 19th century. There were disputes about who was first in the field (as often happens in science). In 1892 a cousin of Charles Darwin, Sir Francis Galton, published Finger Prints (Figure 1), the first major text on fingerprints and their use in solving crime.

Galton, a researcher into heredity, was initially asked to resolve a dispute between two investigators about who had made certain discoveries first. In the process he became fascinated with fingerprints and decided to conduct his own studies that led to his book. In the book, as well as some original insights, he used data and conclusions that had been previously discovered - including the critical one that fingerprints did not change over a lifetime - but he brought it all into one place and established the field of fingerprint use in solving crimes. As a result of Galton's book the British Government in 1894 officially adopted fingerprinting as a supplementary system to visual evidence for the identification of individuals.

Since Galton's days fingerprints have been used all over the world in identification with great success and methods for their visualisation have been constantly improved.

One reason for the enduring usefulness of fingerprints in the administration of criminal justice is that it is very difficult to remove or hide fingerprint patterns. In the 1920s and 1930s in the USA, some prominent gangsters, including the FBI's 'Public Enemy Number One' John Dillinger, attempted to make their fingerprints unrecognisable through self-mutilation. Dillinger had minor plastic surgery to change his appearance and probably at the same time had his finger tips scarred. Sadly for him, enough of his fingerprints remained to enable him to be identified from his fingerprints held on file.

Activity 1: Looking at and taking fingerprints

This activity should take from a few minutes up to an hour or so.

- a.If you have a magnifying glass or a hand-lens, you may like to look at each of your fingertips to see the range of patterns in the ridges. You may also like to look at those of another person in the same way and compare them with yours.

- b.You may also find it interesting to take your own fingerprints and see what kind of features yours show. It can be messy and if you do not have an inkpad, you can buy kits for children that will suit your purposes very well. The kits can also contain dusting powder, brushes and notes on fingerprinting.