3.2 Identifying unfoldings

For the next example of unfolded intervals at work we return to the Sonata in C, K545. This time we are going to look at a passage from the second-subject group, which acts as a transition between the second-subject theme and the codetta theme.

Activity 9

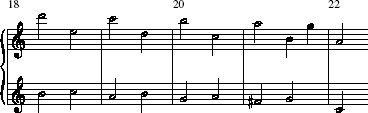

Listen several times to Extract 7 following the score given as Example 17.

Click to listen to Extract 7

Then, on some manuscript paper, make your own analytical graph of these bars by following the steps listed below.

Click to open blank manuscript paper [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

-

Make a simple reduction of the passage by removing the semiquaver figuration and instead writing two minims per bar in each stave. The only exception to this comes in bar 21, where you should write a minim and two crotchets in the right hand.

This should produce the logical piece of two-part counterpoint shown below in Example 18.

-

Look at the right-hand melody of your reduction. You should be able to discover two distinct lines in this part. Overall, in other words, the passage contains a logical piece of three-part harmony.

-

On a fresh pair of staves, but without bar lines, write out the notes of your reduction again as noteheads without stems. To make the harmony easier to read, transpose the left-hand notes down an octave and write them in the bass clef. Add the first and last bar numbers above the stave to help guide your eye.

-

Now turn this version into an analytical graph by adding upward stems to the notes of the upper line within the melody, and downward stems to the notes of the lower line within the right-hand melody, then add downward stems to the main harmony notes of the left hand.

-

Add slurs to show the unfolded intervals, by connecting each note in the lower line to the note with which it harmonises in the upper line of the right-hand melody. Finally, add slurs to each of the three lines (two in the right-hand melody, one in the left-hand) to show the large linear movement.

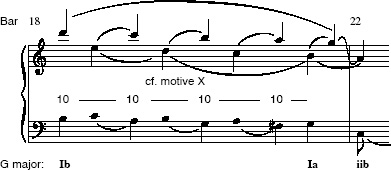

When you have completed your graph, look at my suggested solution given below as Example 19, along with the discussion that follows it.

Discussion

I hope you were able to hear the two large descending lines in the ‘treble’ and ‘alto’ voices, both in the right hand, joined together by arpeggios.

There are several ways in which this passage can be analysed, and the exact details of analytical notation are relatively unimportant. For instance, I asked you to show the unfolded intervals by means of slurs rather than the diagonal beams that were used in Video 1, Band 3; this is purely to make the final graph easier to read. Nevertheless, I hope that your graph looks roughly like mine. What matters is that the graph is able to communicate the way in which you hear the processes and shapes.

Example 19 analyses the unfolded intervals as a set of consecutive sixths. The ‘treble’ and ‘alto’ cannot be moving as parallel sevenths, as this would be bad counterpoint. What happens is that the intervals are staggered across the bar lines to produce the effect of 7–6 suspensions between the two upper voices. As with the graphs built up during Video 1, Band 3, the stem directions clarify the two distinct lines that we hear in the melody. As in some previous examples from AA314_1, the bass runs in parallel tenths with the upper voice, and I have indicated this on the graph.

The ‘alto’ voice in the right hand is especially interesting here. It outlines a motive of four descending notes, E–D–C–B. This is the same shape that I called motive ‘X’ in the analysis of the first subject in the same sonata movement (see AA314_1, Example 14). Here the motive is transposed to the key of G major, rather than C major, since the music has modulated to the dominant. What defines this motive is not just that it is made up of four descending notes, but that these are notes 6–5–4–3 of the new G major scale, and that they are harmonised similarly, with notes 5 and 3 as part of the local tonic chord (C major at the opening of the movement, G major in this transitional passage).

Thus the transition passage of the movement might be said to grow out of the same motivic shape as the first subject (bars 1–4) and its development (bars 5–8). Again, it is an example of a hidden motivic link between material that looks quite different at the surface. Furthermore, the last note (the mediant) comes in each of these three occurrences at the end of a phrase in the music. Look at Examples 19 and 17 to see what I mean. This is an instance of a motive which is partially defined by rhythm, but which is only brought to light by a voice-leading analysis, despite the fact that this form of analysis is often accused of ignoring the role of rhythm.

When you are sure that you understand the features of the music that led me to make my analytical judgements, continue with the next section.