2.1 From point-like stars to diverse nebulae

Stars are fascinating and complicated objects, but for the most part this complexity does not reveal itself in individual images of single stars. Most stars are unresolved to our telescopes (i.e. their light is contained within a region smaller than the size of details we can distinguish).

To understand the structure of stars, astronomers have had to construct models based on information from spectroscopy, studies of binary star systems, and tools such as asteroseismology. However, there are a few exceptions.

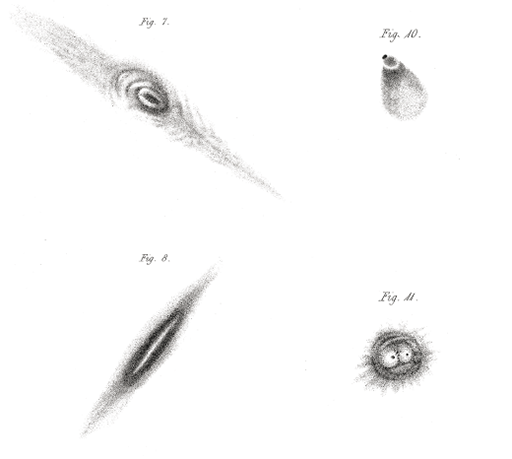

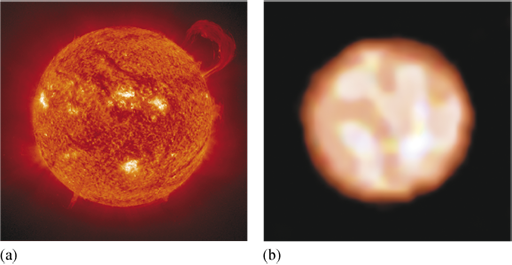

We have exquisite structural information about the surface of the Sun (Figure 7a), from space missions such as the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and Solar Orbiter. This information has enabled astronomers to understand the interplay of energy transport and magnetic fields in our nearest star. We also have a small number of resolved images of nearby giant stars. An example is Gruis (Figure 7b), which shows similar convective structure on its surface to that of the Sun.

For unresolved objects such as stars, the main properties that can be measured from images alone are location, brightness, and colour. But astronomers have known for several centuries that there are objects in the sky that are not point-like – they show extended and varied structure in images. (Extended astronomical objects are defined as those that have an angular size larger than the PSF of an image.) Identification of such fuzzy, ‘cloud-like’ astronomical objects dates back as far as early tenth-century Islamic astronomy.

Early astronomers classified these extended objects as nebulae: nebula being the Latin word for a cloud or fog. The term became used to describe any object that had a fuzzy appearance, rather than the sharper form of a star.

In modern astronomy, the term nebula is now used in a more precise way. However, until the early twentieth century the physical nature of many of the ‘fuzzy’ extended objects in the sky was not well understood, and so the class of nebulae provided a useful distinction between unresolved (point-like) and resolved (extended) structures.

Figure 8 shows some hand-drawn sketches of nebulae dating to the early nineteenth century. It is apparent that they do not all show the same structure: there are various different types of fuzzy, extended – and in some cases a little peculiar – objects visible in the night sky.