4.3 Surveying the variable Universe

Once astronomers have made a detailed map of the sky you might imagine it is ‘job done’, and the survey telescope could be dismantled. Happily this is not the case, because the objects in the night sky are not constant and unchanging – there is much work for astronomers in mapping astronomical objects whose appearance can change from one observation to another.

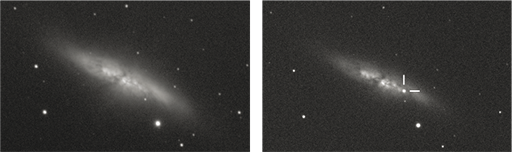

Figure 19 shows two images of a galaxy taken 41 days apart. Can you spot the difference? It shouldn’t be difficult to spot the presence of a very bright ‘star’ in the second image, which has been further highlighted by a position indicator (a vertical and a horizontal bar). This is a supernova: the light comes from the explosion of one of the galaxy’s stars.

In some cases a supernova can briefly outshine all of the other stars in its galaxy, before fading away and the galaxy returning to its usual appearance.

There are many ‘spot the difference’ astronomy surveys underway, comparing images of the same stars or galaxies taken at different times to identify any changes. Finding supernovae is one of the aims of projects such as the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). The LSST, carried out by the Vera C Rubin Observatory, will survey the sky all night, every night, through six broadband filters. It will cover the entire visible sky twice per week, and so build up light curves of billions of stars and galaxies, each spanning ten years. It will also detect huge numbers of transient and variable objects whose brightness varies with time. But there are many other types of variable objects in the sky, including binary star systems and active regions associated with black holes in the centre of galaxies.

Time-domain surveys (i.e. surveys that image the same area of sky many times to look for changes) can be used to study all of these things. Indeed, modern time-domain surveys are able to look across a large area of sky for both periodically varying objects and ‘transients’ – objects such as supernovae that appear and then disappear over a relatively short timescale.

The ESA Gaia survey is another example of a time-domain survey, which has exceptional ability to pinpoint changes in the positions of stars so as to determine their distances through parallax. It can also be used to study changes in brightness, rather than position, including discovering supernovae.