Part 3: 2 Systems practice – unpacking the juggler metaphor

Systems practice, modelled in Figure 23, is a particular form of the general model of practice in Figure 20. An effective systems practitioner, Ps, is able to use systems approaches in managing complexity. I am not overly concerned with other approaches to practice, and will not be making any extravagant claims that a systems approach is better than other forms of practice. I will, however, develop arguments that enable me to make two claims.

Systems practice has particular characteristics that make it qualitatively different to other forms of practice.

An effective (or aware) systems practitioner (Ps) can call on a greater variety of options for doing something about complex ‘real world’ situations than other practitioners do.

These are important claims. They will structure most of the argument made in the rest of the unit.

I intend to build up a picture of an ideal systems practitioner in stages rather than attempting it in one go. Juggling is a set of relationships. A juggler is a person, or living human being, in a particular context, with their body positioned so as to be supported by the floor and in this case they have four different balls. If any of these things are taken away, the juggler, the connection to the floor or the balls then juggling will not arise as a practice. In some situations an audience might also be important, especially if juggling for money. Taking away the audience would destroy the ‘system’, the interconnected set of relationships being envisioned. But there's more to this set of relationships then meets the eye. Take the juggler for example, she or he is both a unique person and also part of a lineage of groups of organisms called living systems. All living systems have an evolutionary past and a developmental past that is unique to each of us – a set of experiences which means that my world is always different to your world. We can never truly ‘share’ common experiences because this is biologically impossible. We can however communicate with each other about our experiences.

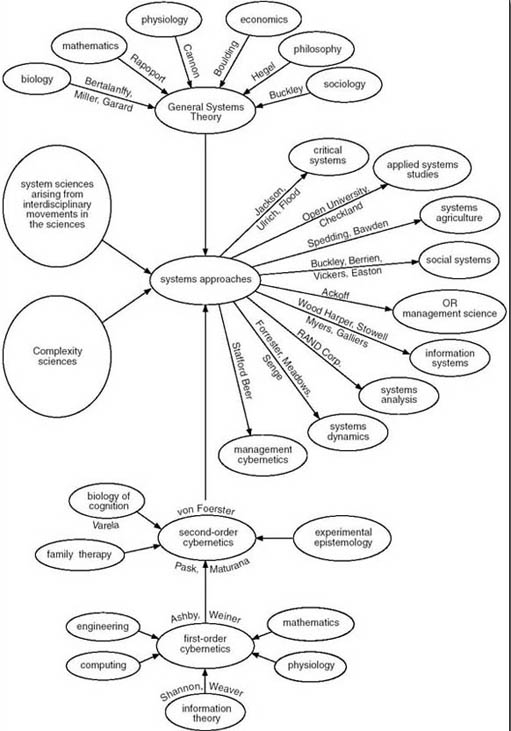

Many well-known systems thinkers had particular experiences, which led them to devote their lives to their particular forms of systems practice. So, within Systems thinking and practice, just as in juggling, there are different traditions, which are perpetuated through lineages (see Figure 24).

Activity 33

Tick off those blobs in Figure 24 which you have heard of or with which you are familiar.

Do a web search and bookmark some sites which relate to those blobs you have not heard about. Use any search engine to do this perhaps starting with the words or people named in the figure as keywords.

Before finishing this introduction to the systems practitioner, I want to examine in more detail each of the balls being juggled.

The first ball the effective practitioner juggles is that of being. Juggling is a particularly apt metaphor in this regard because good practice results from centring your body and connecting to the floor. So juggling arises from a particular ‘disposition’ or embodiment. Effective juggling is thus an embodied way of knowing. Lakoff and Johnson (1999) argue that in the Western world, the most common sense view of what a person is arises from a false philosophical view, that of disembodied reason, that has influenced almost all of the professions. They contrast this with an embodied person (for example in medicine until quite recently the brain was seen as quite distinct from the body – the mind–body dualism – whereas the brain is part of a much larger network that includes the nervous, endocrine and immune systems (e.g. Pert, 1997)). It is for this reason that I have depicted the juggler with the light in their body rather than above their head. The light symbolises embodied understanding.

Activity 34

List the two contrasting ideas from Table 1 that you find most challenging to, or supportive of, your current worldview. Explain why.

| Traditional Western conception of the disembodied person | The conception of an embodied person |

|---|---|

| The world has a unique category structure independent of the minds, bodies or brains of human beings (i.e. an objective world). | Our conceptual system is grounded in, neurally makes use of, and is crucially shaped by our perceptual and motor systems. |

| There is a universal reason that characterises the rational structure of the world. Both concepts and reason are independent of the minds, bodies and brains of human beings. | We can only form concepts through the body. Therefore every understanding that we can have of the world, ourselves, and others can only be framed in terms of concepts shaped by our bodies. |

| Reasoning may be performed by the human brain but its structure is defined by universal reason, independent of human bodies or brains. Human reason is therefore disembodied reason. | Because our ideas are framed in terms of our unconscious embodied conceptual systems, truth and knowledge depend on embodied understanding. |

| We can have objective knowledge of the world via the use of universal reason and universal concepts. | Unconscious, basic-level concepts (e.g. primary metaphors) use our perceptual imaging and motor systems to characterise our optimal functioning in everyday life – it is at this level at which we are in touch with our environments. |

| The essence of human beings, that which separates us from the animals, is the ability to use universal reason. | We have a conceptual system that is linked to our evolutionary past (as a species). Conceptual metaphors structure abstract concepts in multiple ways, understanding is pluralistic, with a great many mutually inconsistent structurings of abstract concepts. |

| Since human reason is disembodied, it is separate from and independent of all bodily capacities: perception, bodily movements, feeling emotions and so on. | Because concepts and reason both derive from, and make use of, our perceptual and motor systems, the mind is not separate from or independent of the body (and thus classical faculty psychology is incorrect). |

Answer

I think the last pair is the most challenging for me and others I encounter – not because I do not accept it on the basis of evidence emerging from over 30 years of cognitive science research, but because it is still difficult to talk about. My experience is that the majority of people take the traditional view so much for granted that the alternative is often dismissed before the conversation can begin. Recently my daughter's teacher responded in this manner in response to points she raised in an essay for her ‘theory of knowledge subject’ as part of her International Baccalaureate studies.

The second I find most challenging concerns ‘conceptual metaphors’. The research conducted by Lakoff and Johnson and others suggest that through our evolution we have acquired a predisposition to structure the world in certain ways – and one of the most basic ways we do this is when we form categories. Let me exemplify this by referring to what they call the ‘container metaphor’. One needs to think of this in terms of say a child's development from birth. For these researchers metaphors have an embodied basis, e.g. a child putting things in and out of any container is a basic experience; later this is internalised as in-out action patterns (‘container’ image schema) followed by literal language application of schema, e.g. ‘Out of the box’; ‘In my pocket’; ‘Out of the cup’; ‘In the fridge’. Then there is progressive metaphorical extension, e.g.

‘Go into the house’

‘I'm in bed’

‘I'm in her class’

‘They won't let me in their group’

‘Keep it in the family’

‘Within the terms of reference’

‘An outsider’

‘Exclusive restaurant’

‘In time’

‘In washing the window, I cracked it’

‘There are lots of houses in London’

‘In love’

‘Let out your bottled up anger’

‘Fall into a depression’

‘I put a lot of energy into this’

‘Pick out the best theory’

‘I give up – I'm getting out of the race’

‘It finally came out that he had lied to us’

‘My kind of person’

The implication of this explanation is that we do not engage in a process of universal reason which is independent of our biological history.

Being, is concerned with embodiment, with our own awareness and thus our ethics of action, the responsibility we take as citizens. How a practitioner engages with a situation is not just a property of the situation. It is primarily a property of the background, experiences and prejudices of being the practitioner. So, in the next Section I will focus on some of the attributes of the practitioner. One of these attributes is awareness, awareness of self in relation to the balls being juggled and the context for this juggling. The nature of this awareness and what it means to be an aware practitioner will be explored.

The second ball is the E ball – engaging with a ‘real world’ situation. It is an engagement that can be experienced as messy and complex, or experienced as a situation where there has been a failure or some other unintended consequence. Or the ‘real world’ could be experienced as simple, or complicated or as a situation or as a system. Because I am primarily concerned with situations that are experienced as complex, I will call this engaging with complexity; later I will expand upon what I mean by complexity.

The third ball is concerned with how a systems practitioner puts particular systems approaches into context (i.e. contextualising) for taking action in the ‘real world’; that's the juggler's C ball. One of the main skills of a systems practitioner is to learn, through experience, to manage the relationship between a particular systems approach and the ‘real world’ situation she or he is using it in. Adopting an approach is more than just choosing one of the methods that already exists. This is why I use the phrase ‘putting into context’, to indicate a process of contextualisation involved in the choice of approach.

The final ball the effective practitioner juggles is that of managing (the M ball). This is concerned with juggling as an overall performance. The term ‘managing’ is often used to describe the process by which a practitioner engages with a ‘real world’ situation. This is a special form of engagement, so later I will explore some of the features associated with managing. Managing also introduces the idea of change over time, in both the situation and the practitioner.

There are clearly many ways in which being, engaging, and contextualising are carried out, or could be carried out. Thus, when considering managing I shall be concerned with managing the juggling in ‘real world’ situations experienced as complex.

I would urge you to keep Figure 23 and the juggler metaphor in mind when you are answering questions because a competent answer will always refer to the relationship between practitioner (you and your being), the approach you are envisaging given the nature of the situation as you and other stakeholders perceive it (i.e. your mode of engaging with a situation of interest), how you envisage adapting your practice to the circumstances (contextualising) and how you plan to manage the overall activity.